70 Years After Brown: A Reflection on Democracy and Education

I remember well the day that Ms. Bunny Vance, my first-grade teacher in a segregated school in Jacksonville, Florida, explained to my class that segregation in schools and other public places was wrong. She also taught us that as Black children we could learn just as much as White children. Ever so importantly, my first-grade teacher taught us that as Black children we had to do our part to help to end segregation when we grew up. I clearly heard and accepted my first-grade teacher’s charge; it was the same as I had received from my parents, family members, and community leaders.

I also remember where I was and how I felt on May 17, 1954, when the US Supreme Court ruled in a unanimous decision that state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional. When the news of that Supreme Court decision flooded the airwaves in our country, I was a 15-year-old student in an early entrance program at Fisk University, a historically Black university in Nashville, Tennessee. Along with people across my country, I rejoiced over that landmark decision.

It was a historic decision that overturned the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which held that racial segregation laws did not violate the US Constitution as long as the schools of Black and White children were equal. The unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) also paved the way for integration in other areas of life in our country. And it was heralded as a major victory of the civil rights movement.

Today, seven decades since the Brown decision, education in our country still has not lived up to what that historic decision promised. Today, students in the United States are more racially and ethnically diverse than in 1954, but our public schools remain highly segregated along racial, ethnic, and class lines.

The Enduring Challenge of Segregation

Large numbers of students of color attend schools that are still essentially segregated, and their schools have fewer resources than schools where the majority of students are White. This is a 21st century form of segregation that persists not only in traditional public schools but also in all types of schools such as magnet and charter schools.

When I was a youngster in Jacksonville, Florida, before the Brown decision, where a child went to school was based on the color of their skin. Today, 70 years after Brown, that determination is increasingly based on a student’s zip code, and our country is still a long way from a more perfect union.

Indeed, we are in a period of heightened partisanship and divisiveness. The overwhelming majority of Americans live in neighborhoods with people who look like them, do the same or similar types of jobs that they do, eat in the same restaurants that they do, go to the same places to worship, and send their children to schools where the majority of students are like their youngsters in terms of their racial, ethnic, and class identities.

A Roadmap to Inclusion

Is this not a time, indeed the time, for honest and courageous conversations about how the promise of the Brown decision can become a reality? What are the basic steps that each of us can do to come closer to an educational system that is the bedrock of a truly inclusive and democratic society?

- First, we need to acknowledge that our public schools still remain largely segregated. As James Baldwin said in his 1962 essay: “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed that is not faced.”

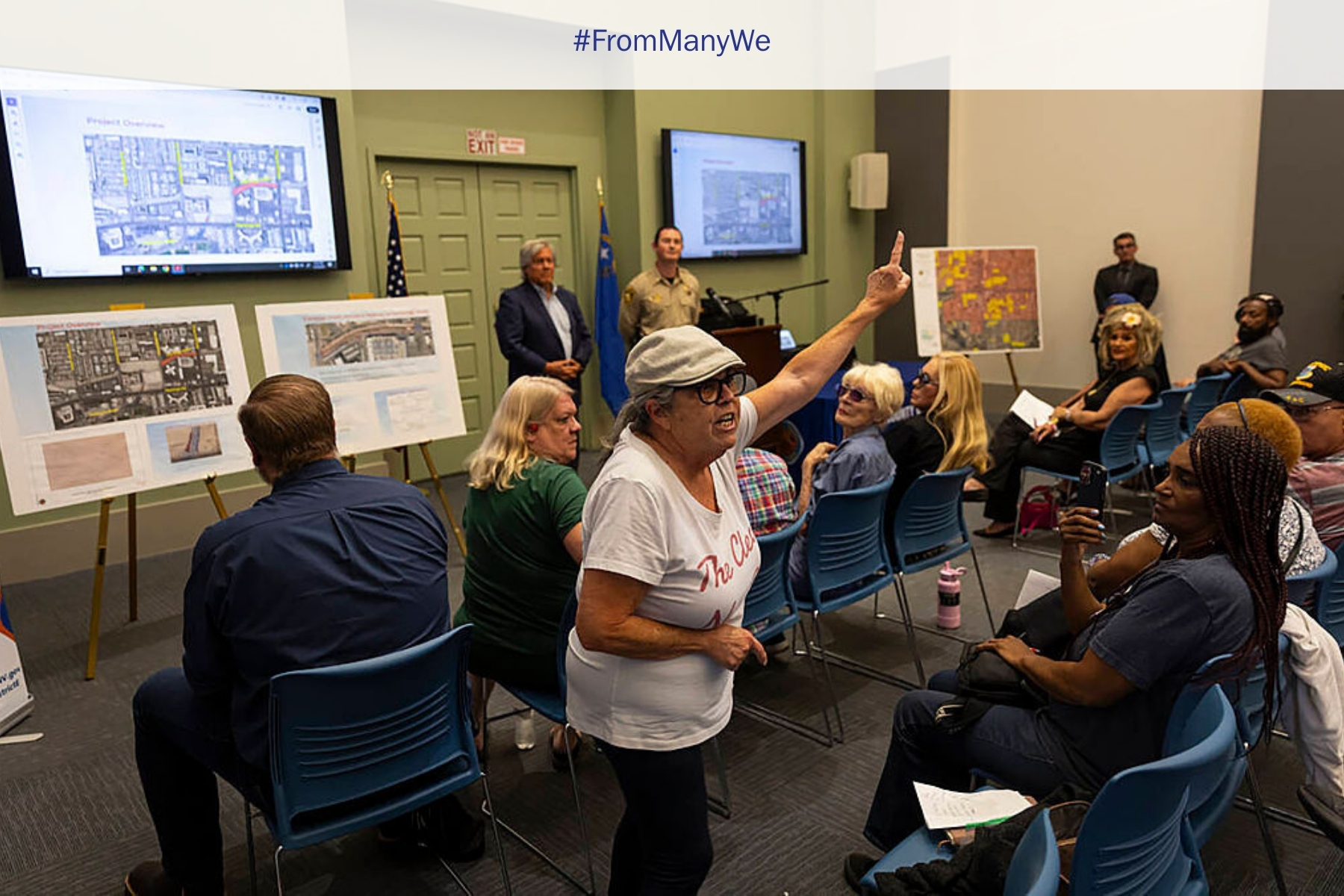

- Second, fulfilling the promise in the Brown decision requires each of us to become more genuinely engaged in all of the issues surrounding public education in our country. We need to pay attention to who is sitting on a school board, push back against the banning of books, ask why teachers continue to be insufficiently paid, and hold accountable our local, state, and national elected officials who have power over how our children are educated. Obviously, whether or not we vote and who we vote for has a direct impact on our public schools.

- Third, we must find ways to adequately fund all of our public schools. It is not hyperbole to say that our democracy depends on it. As President Barack Obama stated: “And if you think education is expensive, wait until you see how much ignorance costs in the 21st century.”

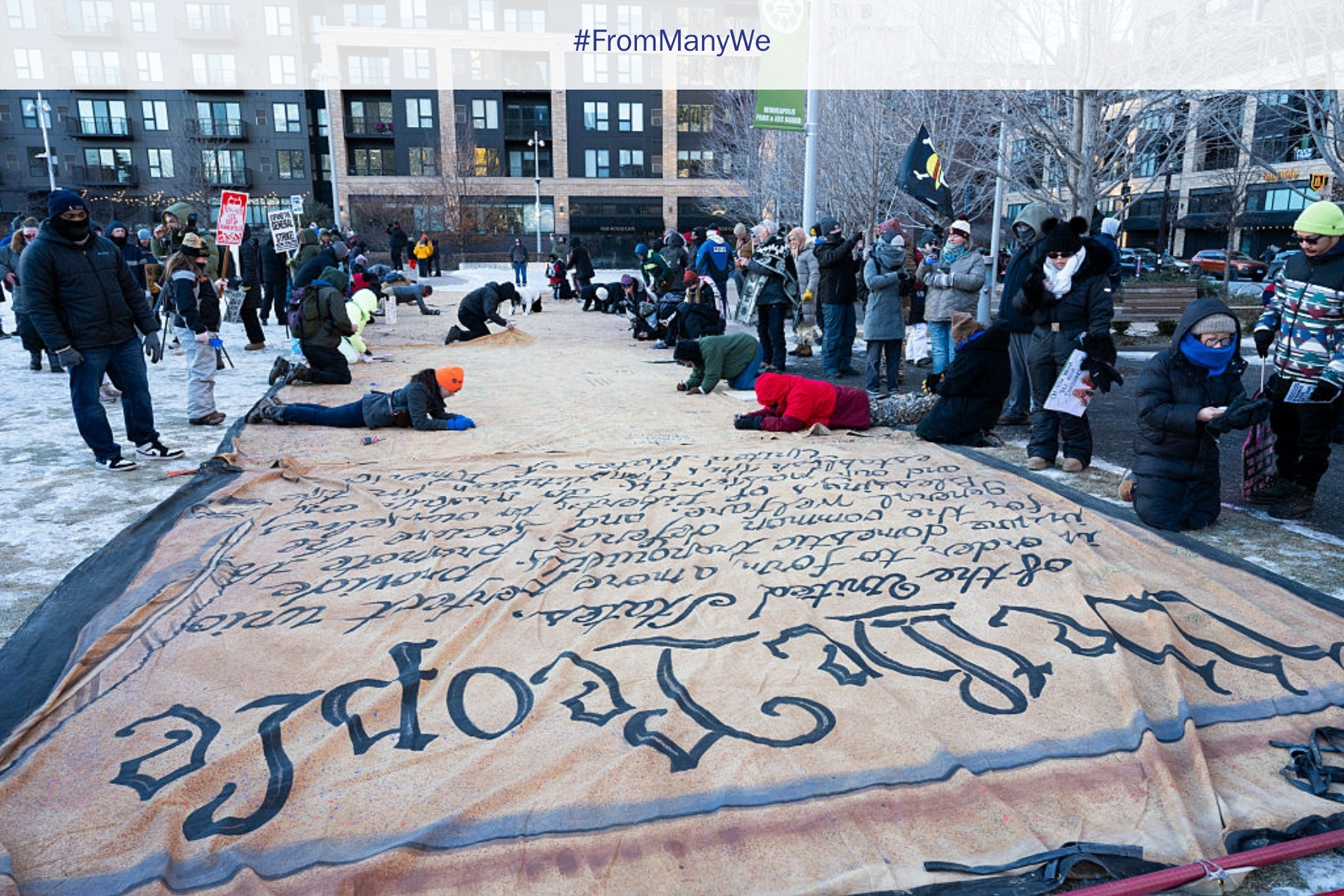

- Finally, we must find effective ways to reach out across our differences to find common ground on the issues that are fundamental to our democracy, like public education. Indeed, all of us must seek ways to move our nation to the point where our differences no longer make such a difference.

Johnnetta Betsch Cole is a noted anthropologist, educator, author, speaker, and consultant on diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion in workplaces. She is the former president of both Spelman College and Bennett College and currently is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation senior fellow.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.