Africa’s Gen Z: Democracy’s Last Line of Defense

The African continent has 400 million youths aged 15–35 years, and they are playing a major role in determining the pulse of democracy. Young people are the largest voting cohort in Africa. In South Africa, they constitute 42% of registered voters and are 62% of the voting population in Ghana. They have driven major protests, including the most recent one in Kenya. However, they have also supported coups in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Zimbabwe and have been at the center of popular uprisings that have yielded to military-led transitions in Egypt and Sudan. African youths prefer democracy to authoritarianism, but they are more likely than their elders to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is currently working in their countries. The danger is that if the aspirations of youth are not addressed via democratic processes, their dissatisfaction with the establishment may give way to support for authoritarian alternatives.

From Winds of Change to Autocratization

The coups pose a significant threat to the ongoing process of democratization that Africa earnestly began in the 1990s. During this time, the Wind of Change brought a legal shift from one-party states into constitutional multiparty democracies. A new compact against military coups was also formed. The African Union and the Economic Community of West African States adopted a resolution to not accept governments that emerged out of military-led establishments. The consensus lasted for at least a decade. Since the early 2000s, evidence is also pointing toward reversing these democratic transitions to non-democratic regimes in a third wave of autocratization.

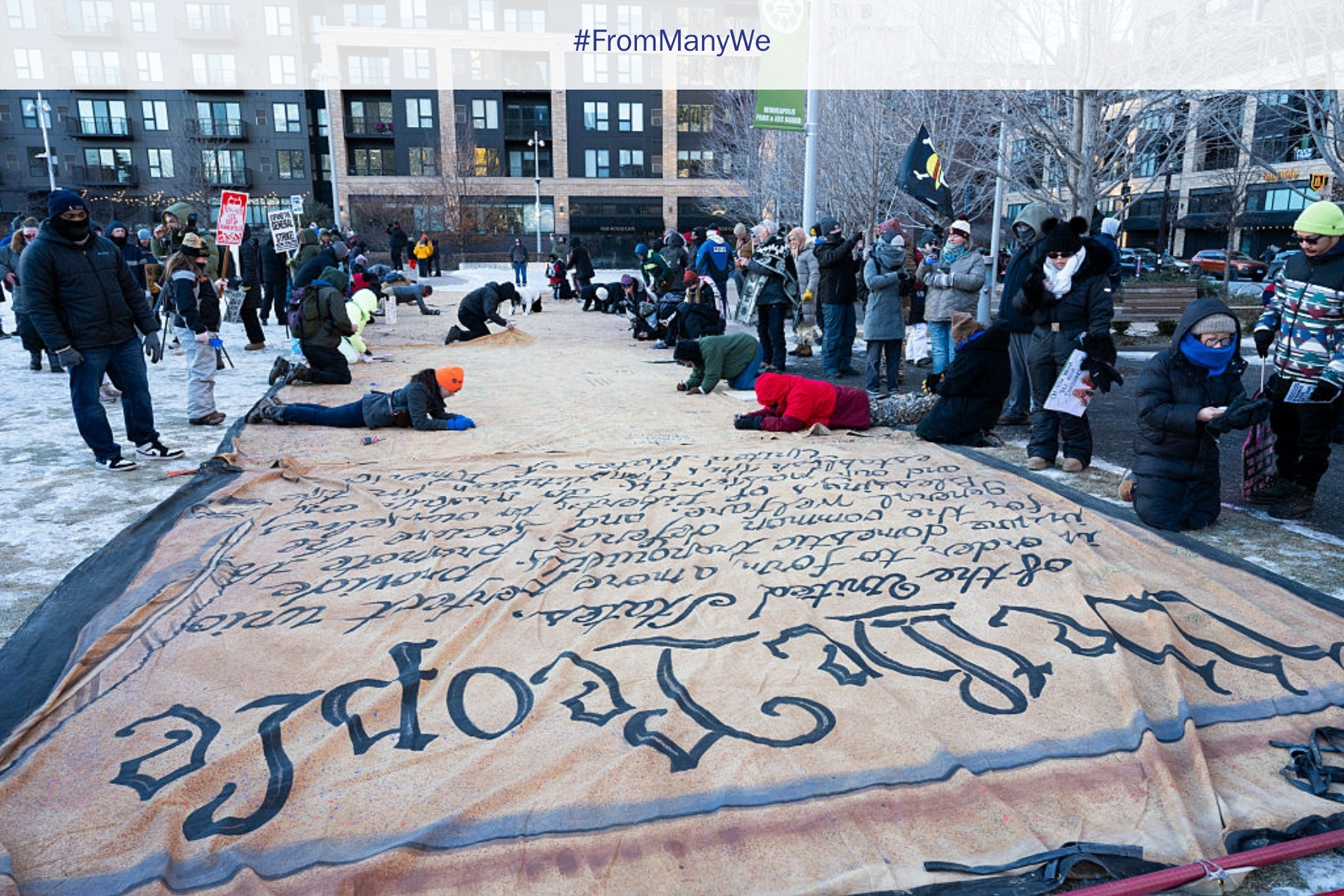

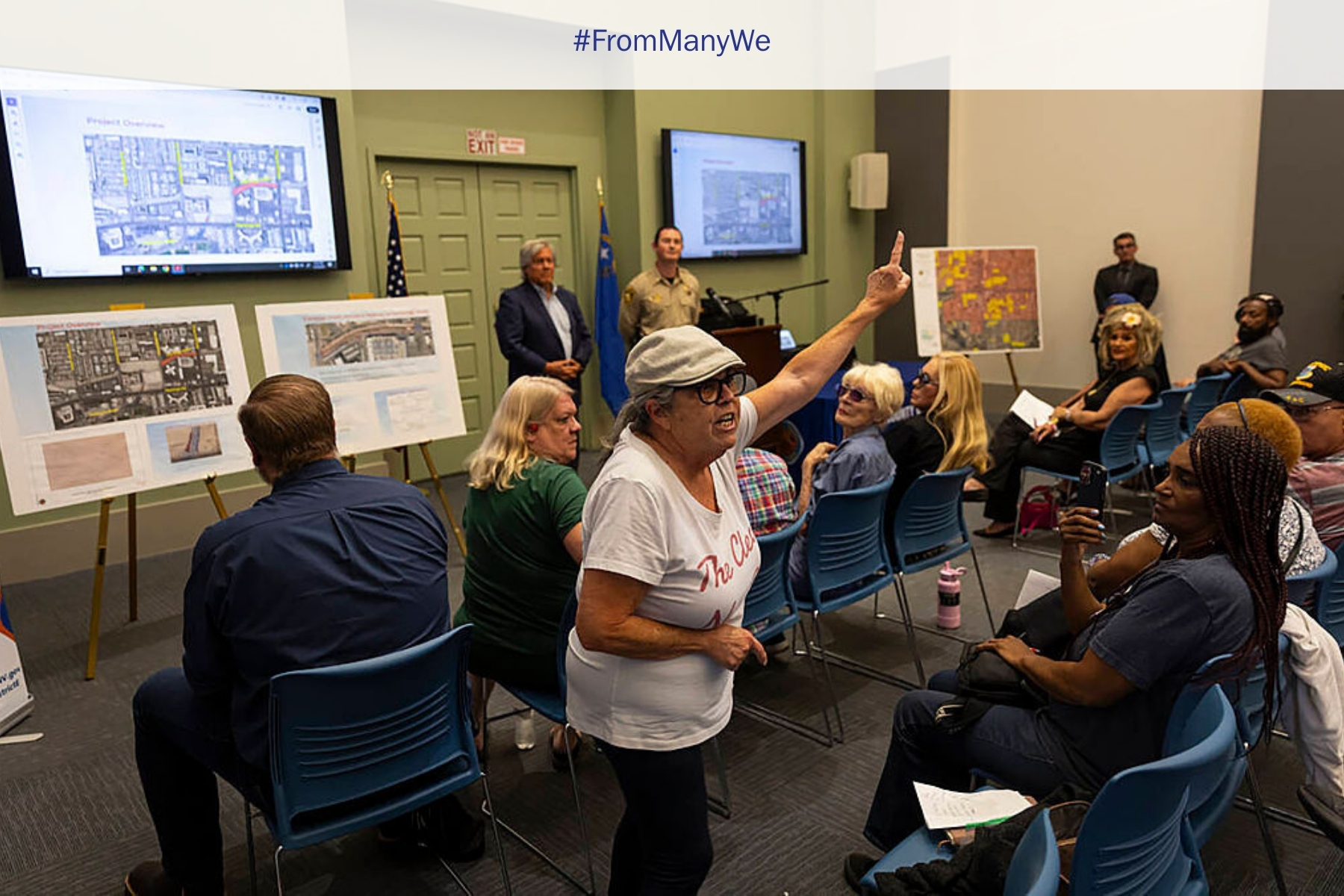

Despite the role that young people have played in supporting recent military coups, there is excitement about the potential of a Gen Z-driven democratic consolidation across Africa. The Afrobarometer report also notes that late millennials and Generation Z have broadened their political behaviors beyond voting to embracing collective action to advance new democratic ideals. But the same youth have a greater willingness to tolerate military intervention when elected leaders abuse power. They are also less trustful of government institutions and leaders. Furthermore, the findings from the Afrobarometer survey may suggest youth attitudes toward democracy are contradictory, but they may also point toward flexibility in dealing with existing contexts. The youths are probably more interested in the performance of political regimes than the rhetoric of democracy. The Kenyan youth have been actively demonstrating against specific government policies. The public role of African youth has mostly entailed protesting (at times violently) against economic injustices, corruption, police brutality, governance, and election-related concerns.

- Since the Arab Spring, youth movements have helped remove long-term authoritarian regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. However, their role in Zimbabwe is somewhat disputed given the central role of the military in orchestrating the change of government.

- In Malawi, the youth played a central role in disputing what was perceived as a rigged outcome of the 2018 elections. The attention led to the nullification of the results and new elections.

- In Senegal, youths successfully protested former President Macky Sall’s decision to imprison opposition political leaders and postpone the elections. A number of youth leaders that had been arrested were then released, and the election postponement was ruled illegal.

- In Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa, the youths have protested the unaffordable costs for tertiary education (#feesmustfall), police brutality (#endsarsnow), economic crisis, and rising youth unemployment. The abuse of international debt has been publicly rallied against in Ghana and Zambia.

These protests are not one-off events. In some countries—Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, and South Africa—it has become normal to witness at least four protests a month. The specific grievance or rallying point may shift, but the root problems are always the economy, the increasing cost of living, and governance blunders.

In 2024, the Kenyan #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests have not only animated the African public space but also inspired movements beyond the continent. The Gen Zs of Kenya (a seemingly leaderless movement) successfully protested the imposition of a new tax that the government intended to use toward settling international debt. The original draft of the bill would have increased levies on basic daily needs such as fuel, mobile money transfers, internet banking, sanitary pads, and diapers.

These protests suggest a broadened understanding of democracy beyond elections. From the youths’ perspective, democratic governments should be able to resolve economic and social injustices. They are focused on reforming not only the national but also international political and economic frameworks. At the national level, they have sought to expose and, where possible, remove a corrupt and illegitimate government. At the international level, the Gen Zs have devoted their energies to challenging remnants of colonial power, especially in Francophone Africa and the international financial system. In Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Mali, there has been a consensus to challenge French hegemony in the affairs of former colonies. The youth vote in Senegal was in many ways an expression of their discontent with how the French continued to exercise power, especially around economic reforms and fiscal policy. Rallies in Kenya have been largely against President William Ruto, but protesters are also speaking out against the IMF. Gen Z protesters throughout the African continent are focused on the wasteful local elite and on what they call irresponsible lending and unfair interest rates.

Beyond Protests

Conversations about youth participation in the state of democracy across Africa are often reduced to a counting of first-time voters. Such discussions remain disconnected from the wide-ranging protests discussed above. The protests are usually successful. In Kenya, after six weeks of demonstrations and a promise to reverse the bill, President William Ruto fired his cabinet and pledged to cut wasteful spending.

However, there is limited evidence to suggest that youth-led movements have imagined new democratic frameworks beyond their participation in voting, protesting, and ensuring accountability. Youth-led organizations focused on government accountability have grown in number and influence over the years. They have leveraged technology to track government expenditures, established commitments to policy reform, and mobilized more youth participation. They have pushed back on the global financial system and its treatment of poorer countries. However, all these actions can appear to be simply tinkering on the edges of a continent that may be drifting into a new era led by popular authoritarians. To avoid this outcome, the youth movement must continue to play a more active role in governance instead of simply being facilitators of political transitions.

Tendai Murisa is a researcher and development practitioner focusing on democracy and governance across Africa. He has been a fellow of the Kettering Foundation in 2013 and 2018. He is the founder and executive director of the SIVIO Institute.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.