Censorship, Solidarity, and Resistance

I’m increasingly concerned by the efforts of the Trump administration to censor artworks and histories that don’t align with its political ideology. Even if you are not directly involved with the arts and humanities, you should be concerned too. These efforts, which suppress what the administration describes as “improper ideologies” and “objectionable art,” threaten anyone who cares about things like the freedom to express ideas without being intimidated, being treated fairly, and having access to an accurate account of our history. In addition, they undermine the foundational values and practices that the United States, as a democracy, has sought to embody since its inception.

I am also deeply concerned about the ripple effect. This includes copycat actions in some states and the self-censoring of organizations and institutions. Individuals are also affected in very personal ways. I’ve noticed that I now think twice about expressing my opinion, not only online but also in private conversations. That, in part, is why I’m writing this essay: to resist self-censoring.

The power of the arts and humanities is demonstrated by the considerable effort being devoted to control what is displayed in our public and private institutions, created by artists and writers, taught in schools and universities, and made available in our libraries and media. Why else would the administration put so much effort into censoring and punishing individuals and institutions who resist these efforts?

More than fields of study, the humanities offer us ways of exploring what it means to be human through expressing our own thoughts and feelings and exploring our family histories and experiences. Through engaging with an array of perspectives and cultures through literature, art, and history, individuals can learn to appreciate their own unique experiences and values, and those of others.

For some, the arts may seem to be simply a form of entertainment. For others, irrelevant. Yet the arts, understood as the creative expression of ideas, feelings, and experiences, can be for everyone. The arts can make connections between the personal and the public, the heart and the head. The arts can make democracy concrete and relevant because they are so very connected to our senses and lived experiences. The arts in all their various forms can embody the things we hold dear in democracy, things like belonging, trustworthiness, being treated fairly. They can embody history.

Earlier this summer, following an executive order titled, Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History, the administration sent a letter to the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution to initiate a “comprehensive internal review of selected Smithsonian museums and exhibitions. . . . to ensure alignment with the President’s directive to celebrate American exceptionalism [and] remove divisive or partisan narratives.” The letter ordered the Smithsonian to remove “divisive” narratives and “race-centered ideology” from its exhibitions and install what the administration characterized as “unifying, historically accurate, and constructive descriptions.”

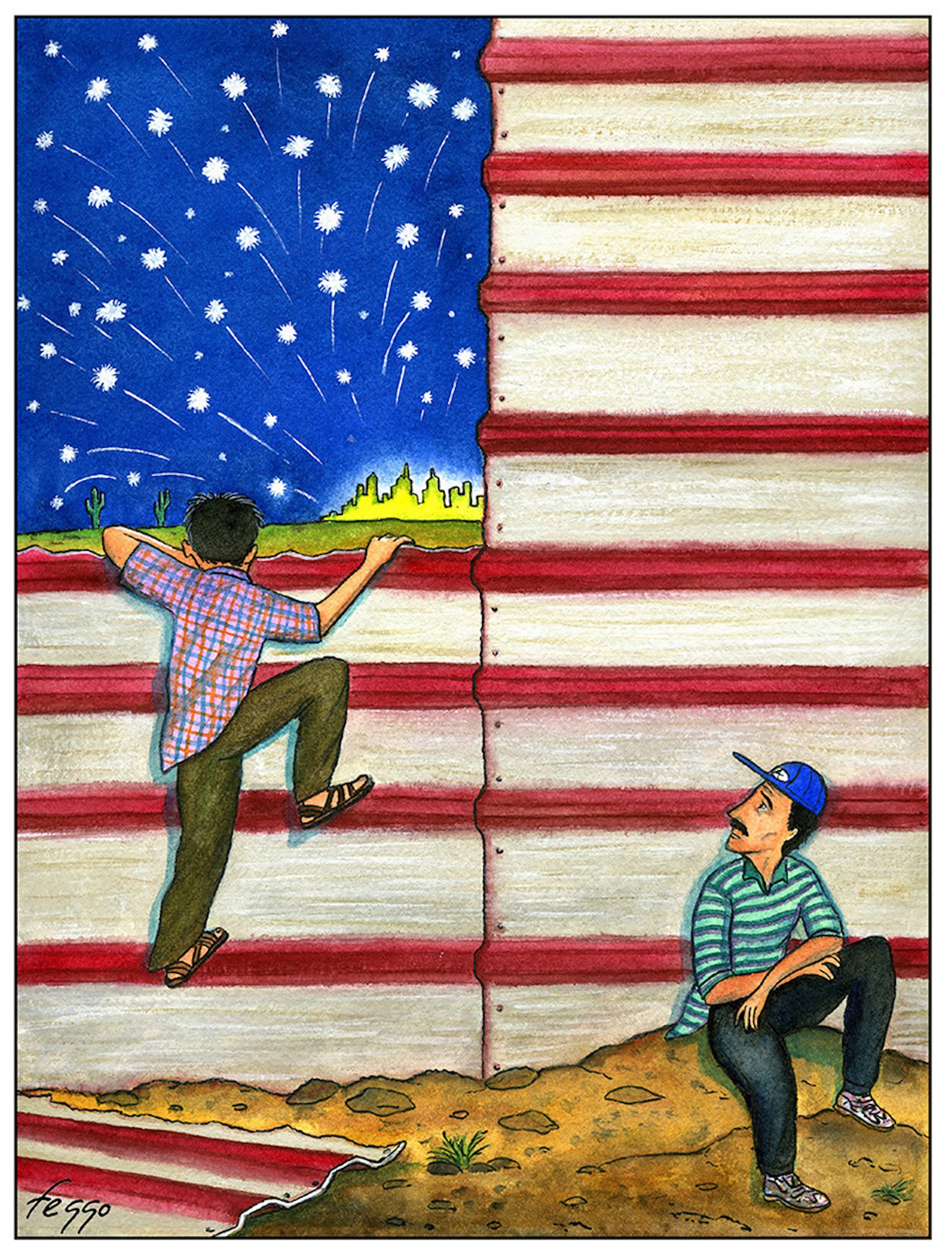

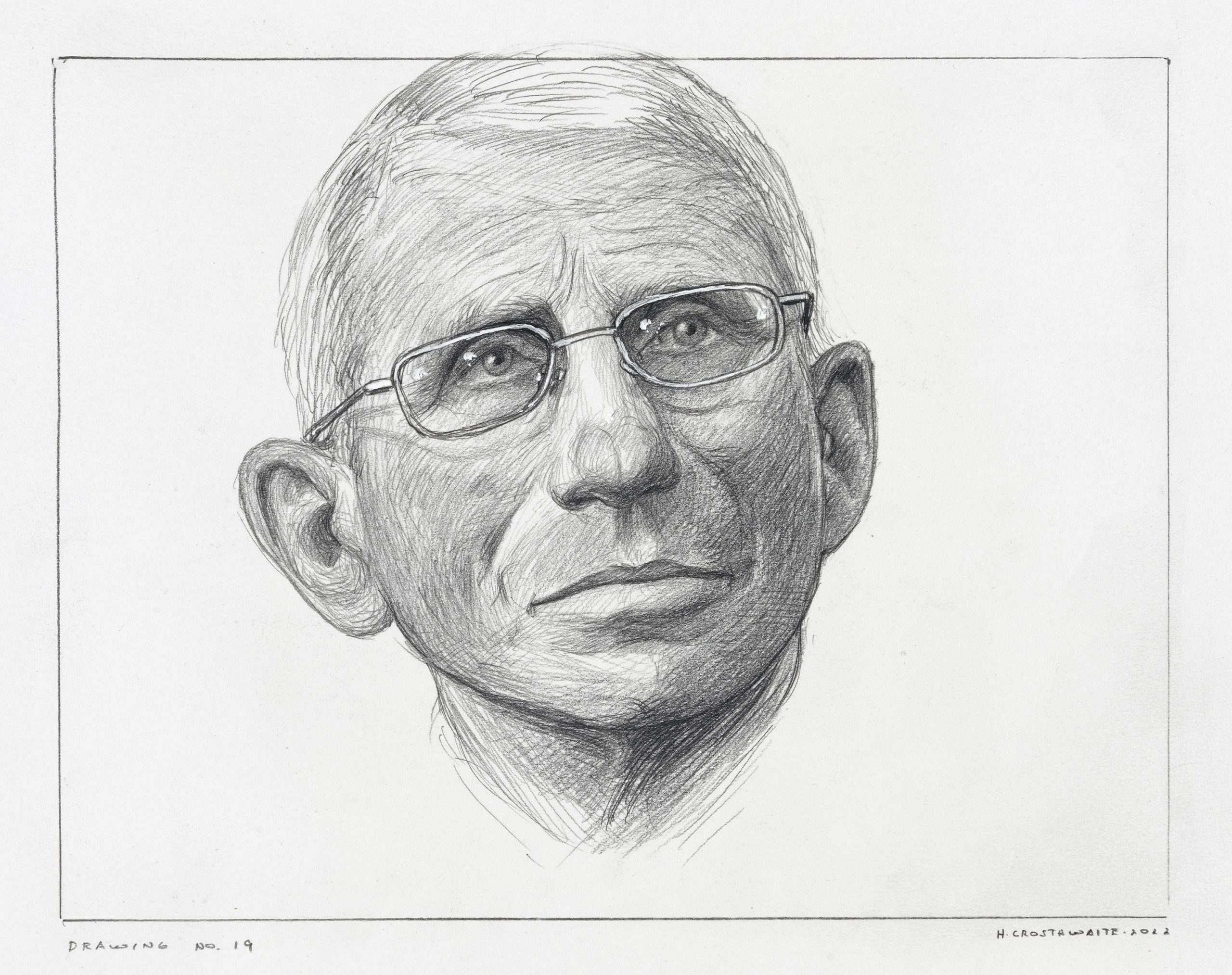

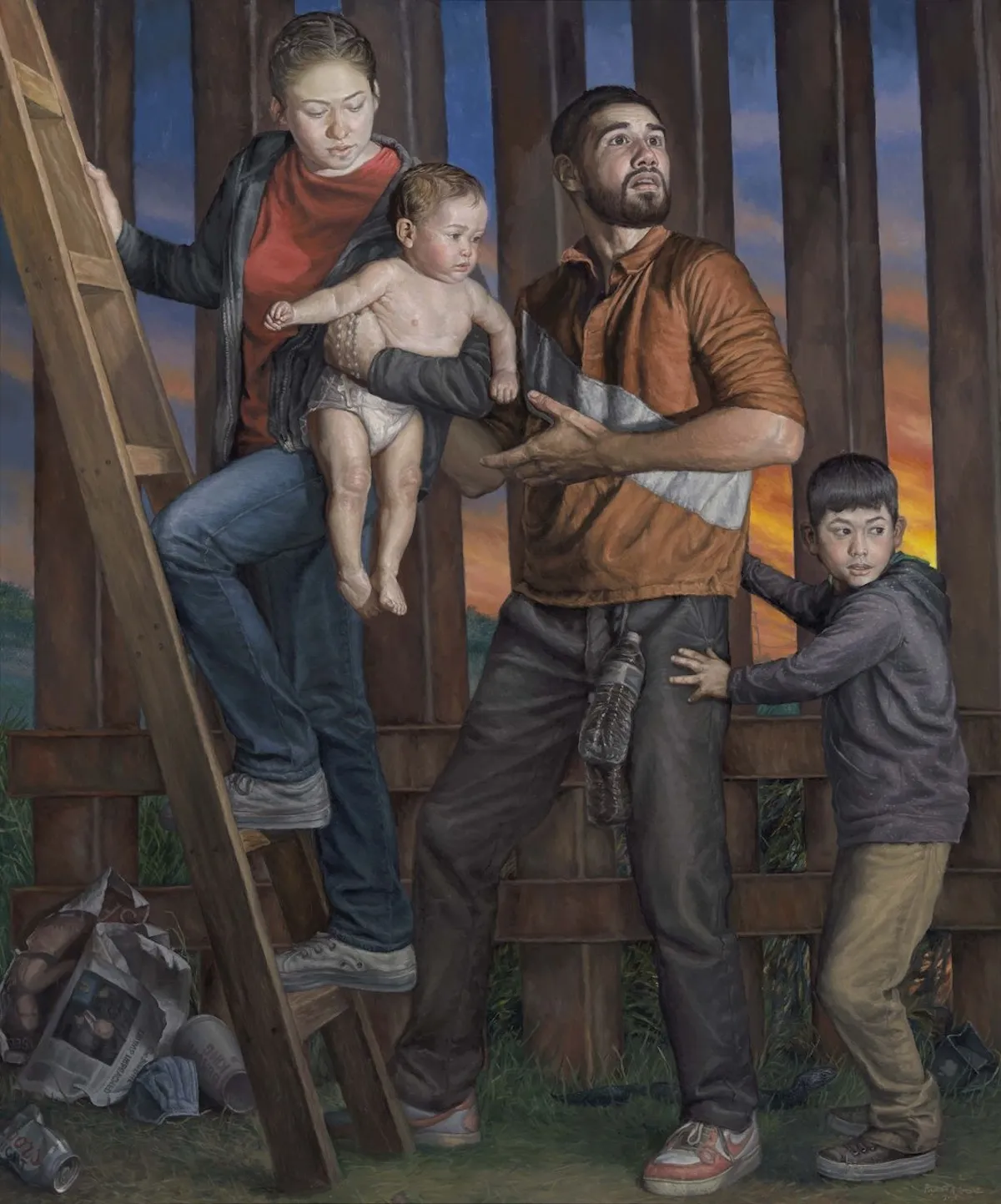

After the White House published a list of Smithsonian artworks it deemed objectionable, the National Museum of the American Latino’s exhibition, ¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States, on view at the National Museum of American History’s Molina Family Latino Gallery, was closed. This list included Felipe Galindo Gómez’s 4th of July from the South Border, a reproduction of which was on view in the exhibition. And instead of a 2026 exhibition about the Latino civil rights movement of the 1960s, the museum is now planning a salsa show. The National Portrait Gallery was denounced by President Trump for commissioning A Portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci by Hugo Crosthwaite and for exhibiting Rigoberto A. González’s painting Refugees Crossing the Border Wall into South Texas. Both were characterized as objectionable by the White House.

Recently, the president directed the National Park Service to drop transgender and queer references at the Stonewall National Monument, which, ironically, is dedicated to LGBTQ+ history. It also ordered information on slavery and Native Americans to be removed from national parks and monuments. One example is the removal of signs and other materials that recognize the land once belonged to Native American tribes. Another is the elimination of references to slavery at several sites commemorating the Civil War. Philippe de Montebello, the former director of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum, once observed, “A museum is the memory of mankind.” In an article in The New York Times, Stephanie McCurry, a professor of history at Columbia University, said it was impossible to separate slavery from the history of these sites because “there is no history of the U.S. without slavery in it.” That appears to be what this administration is trying to do.

This August Hyperallergic published an essay by Vedet Coleman-Robinson, president and CEO of the Association of African American Museums. She reminds us that “interpreting culturally diverse stories and artifacts is not what divides us. What divides us is the omission of those stories under the pretense of neutrality. Teaching American history without the full truth is what creates division. . . . The American story includes joy and pain, triumph and injustice, brilliance and resilience. . . . Removing African American stories from this tapestry doesn’t just harm Black communities—it impoverishes our understanding of the nation as a whole.” During these times, she argues that “preserving history is not a passive act; it is an act of civic courage. . . . The role of museums is not to protect us from history, but to prepare us for the future. . . . In this moment, honesty is patriotism.”

In a recent guest essay published by MSNBC, artist Amy Sherald expressed a similar perspective: “This country’s story has always been a contradiction. Slavery alongside freedom. Erasure alongside invention.” She warns, “When governments police museums, they are not simply policing exhibitions. They are policing imagination itself.”

The severe cuts to funding and staffing at the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities are another effort to undermine the reach of the arts. The administration is trying to defund the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences, a significant source of support for libraries and museums. What happened at the Kennedy Center can be seen as a form of hijacking. President Trump said, “We didn’t like what they were showing and various other things. I’m going to be chairman of it, and we’re going to make sure that it’s good and it’s not going to be ‘woke.’”

In addition to what’s happening in Washington, many arts and humanities organizations across the country have had grants rescinded. All previously approved Congressional funding for PBS and NPR has also been withdrawn. These public broadcasters provide free, nationwide access to arts and culture through offerings such as PBS NewsHour, Great Performances, American Masters, Morning Edition, and All Things Considered, all of which deliver arts and humanities content and educational resources.

Hitler’s campaign against the arts resulted in the confiscation of more than 20,000 works of “degenerate” art—art which he believed was created by “sick minds”—to advance an Aryan racial hierarchy and to dehumanize others. Stalin also censored artists and writers who did not support an idealized depiction of life in the Soviet Union. In addition, Hitler and Stalin gained control over television and radio and weaponized the visual arts, film, and literature to advance state propaganda. The similarities are clear. It can happen here. It is already happening here.

We don’t need to turn to Europe or Russia to learn about fascism. For centuries, African Americans have experienced the violence of fascist beliefs based on racial hierarchies. As Kimberlé Crenshaw has observed, the effort to erase “our racial history and its present consequences . . . is among the least talked about dimensions of our slide into fascism.” She goes on to say, “exclusive notions of who belongs and who doesn’t are fundamental features of fascist regimes.”

As the Human Rights Foundation posted in a blog titled, “The Silencing of Dissident Artists,” “Authoritarians have always understood a certain truth: creativity is a threat to their power.” Creativity can also be a form of resistance. Examples range from the colorful posters displayed in No Kings protests to the boycotting of the Kennedy Center to recreating the Pulse Memorial crosswalk with chalk after the painted version had been removed by order of Governor Ron DeSantis at the request of President Trump.

Resistance also occurs in more traditional ways. A number of humanities councils, which offer educational and enrichment programs in every state and territory in the country and the District of Columbia, are fighting the rescinding of grants in court.

These examples include the acts of everyday people as well as organizations and institutions. Resisting the urge to self-censor, while not easy, is an important first step.

Joni Doherty is senior program officer for Democracy and the Arts at the Kettering Foundation.

Images:

Rigoberto A. González, Refugees Crossing the Border Wall into South Texas, 2020, oil on linen, Valmar Private Collection, https://portraitcompetition.si.edu/exhibition/2022-outwin-boochever-portrait-competition/refugees-crossing-the-border-wall-into-south-texas/.

Felipe Galindo Gómez, 4th of July from the South Border, 1999, ink and watercolor on Arches paper, 36 × 29 cm, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018648700/.

Hugo Crosthwaite, A Portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, 2022, stop-motion drawing animation and 19 pencil drawings, 4:59 minutes, National Portrait Gallery, https://portraitcompetition.si.edu/competition/commissioned-works/portrait-dr-anthony-fauci/.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.