Disinformation and Identity: A View on Media and Authoritarianism from the Americas

On October 14, 2024, the Kettering Foundation released a Democracy around the Globe webinar exploring how authoritarian leaders use disinformation to divide publics, mobilize supporters, and diminish opponents. Featured speakers included:

- Roberta Braga, founder and executive director, Digital Democracy Institute for the Americas (US)

- Samantha Bradshaw, director, Center for Security, Innovation and New Technology, American University (US)

- Raquel Recuero, Center for Languages and Communication, Federal University of Pelotas (Brazil)

The author’s analysis of the discussion and its key findings follows.

For four years, Donald Trump told Americans that their elections could not be trusted. He insisted that the 2020 election was rigged and that the 2024 election would be too. In the end, Trump won reelection handily, without the need for false claims of fraud. Facts and falsity proved largely irrelevant, and leading observers are now calling for a rethink of countering disinformation as both a theory of change and a field of practice.

Disinformation, and efforts to counter it, is about more than truth and falsehood. Rather, each is best understood as being a struggle between the narratives that play on citizens’ identities and are used to shape political perception. Roberta Braga described these narratives as “stories about the state of the world” that incorporate facts and falsehoods into a frame; that frame can itself be true, untrue, purely subjective, or a combination thereof. These stories often appeal to identity issues by drawing on racist, sexist, and homophobic rhetoric.

During the webinar, Brazilian academic Raquel Recuero gave the example of her own country, where former President Jair Bolsonaro used social media to communicate directly with throngs of supporters. Recuero says these supporters developed a deep emotional bond to Bolsonaro, similar to soccer fans identifying with a team. Bolsonaro based his appeal on returning the country to “the good old days,” which he claimed had been ruined by Brazil’s corrupt, leftist elite. According to Bolsonaro, only he—backed by the military—could reverse the damage. In a majority Catholic country, rocked by a major corruption scandal, this narrative—along with his rejection of feminism and his homophobia—also resonated with many conservative voters.

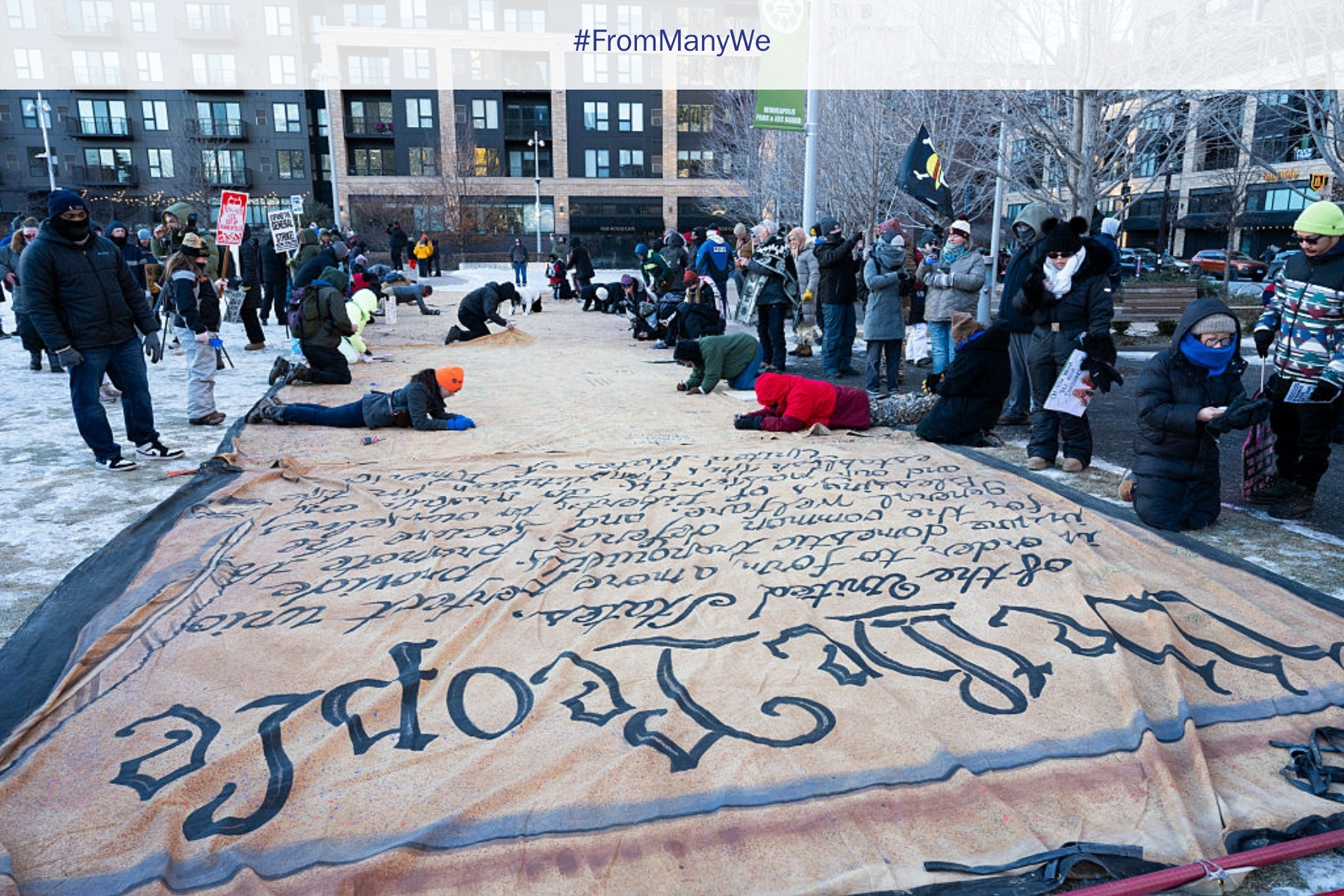

Supporters who wanted more of Bolsonaro’s pitch could find unlimited amounts online, where they connected with other supporters in an environment unmediated by professional journalists or traditional media gatekeepers. Previously taboo ideas, like the idea that democracy might have to be overthrown in order to save it, became more mainstream and were legitimized by the shared sense of identity among adherents. Ultimately, Bolsonaro’s electoral defeat in 2022 led to riots in Brazil’s capital that were reminiscent of America’s January 6th insurrection after Trump’s loss in 2020. Given the close relationship between the two men and their movements on opposite ends of the Western Hemisphere, these riots were likely not a coincidence.

The Information Deficit Paradigm

Over the last eight years, responses to disinformation have largely underestimated the role of identity issues and placed too much emphasis on debunking and literacy initiatives. Scholars like Rachel Kuo and Alice Marwick warn that these responses are aimed at correcting perceived information deficits and are ill-suited for addressing the narratives that appeal to race, gender, class, and other facets of identity. As Théophile Lenoir and Chris Anderson write, these strategies “often frame large parts of the population as irrational beings that can be easily manipulated . . . [leading] to political constructions where, with the right information, people would make the right political choices.”

As panelist Samantha Bradshaw stated during the webinar, “You can’t just label racism, [and] you can’t just fact-check sexist claims.” She recalled the use of narratives about race and feminism by Russian actors hoping to divide American activists during the beginning of the first Trump administration. Her research shows how identity-based disinformation can mobilize support and demobilize opposition.

A New Strategy: Transform the Information Environment

Bradshaw is the author of a new paper, “Disinformation and Identity-Based Violence,” in which she asks how considering disinformation as an identity issue might more effectively mitigate disinformation and the harm it causes. She explores the human dimensions of the biases and prejudices that disinformation thrives on and perpetuates and the role of social media platforms that often reward controversy, anger, and fearmongering. Addressing disinformation through the provision of true information alone is not enough to mitigate the harm directed at broad communities of people. Bradshaw calls for building “a culture of digital peace,” which would address the human dimensions by working directly in communities to build civic capital, social trust, and renewed pluralism. The technological dimension would be addressed by making the online media environment less rewarding for divisiveness and hate.

Panelist Roberta Braga believes that academics, policymakers, philanthropists, and activists should acknowledge the complexity of the human beings whose views are influenced by disinformation narratives. For example, in the United States, many observers fear that Spanish-speaking communities are more vulnerable to mis- and disinformation, but Braga warns that treating communities as monolithic can backfire. In her work, factors like a generally conspiratorial mindset or time spent in hyperpartisan media spaces are better predictors of belief in disinformation narratives than demographic variables like ethnicity. Braga also believes that stakeholders in the United States can learn from counterparts in Brazil and elsewhere, saying that the relationship between Western countries and the global majority should be less like that between a parent and child and more like a relationship between peers.

Despite eight years of work to counter disinformation work since Russia’s attempts to interfere in the 2016 election, Trump’s reelection emphatically makes the point that voters will not simply reject authoritarian leaders after being presented with the right facts in the right order. In a reflective postelection note, disinformation researcher Jared Holt said a better way forward will require the field to challenge its assumptions and explore more imaginative approaches. In the months to come, stakeholders should devote time and resources to mapping those approaches out more fully. Responding to identity-based disinformation requires a shift in strategy and a renewed focus to reckon with the roles of human bias and technology in propelling the disinformation on which authoritarians rely.

Dean Jackson is the principal of Public Circle, LLC, and a contributing editor at Tech Policy Press. In 2022, Jackson was an investigative analyst with the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the US Capitol.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.