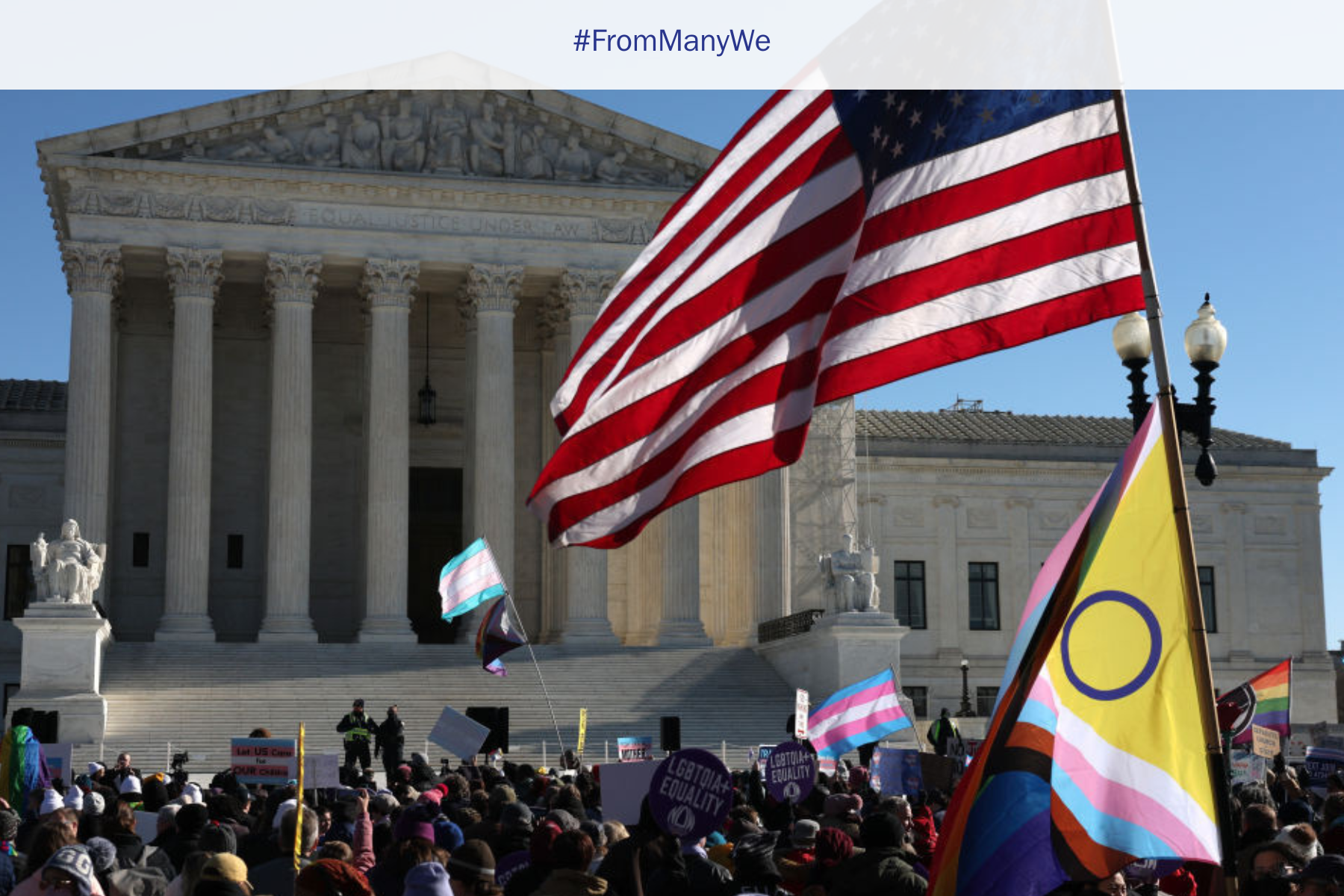

A License for Discrimination: The Supreme Court’s Anti-Trans Ruling Threatens the Foundations of Legal Equality

On Wednesday, June 18, the Supreme Court issued a devastating 6–3 ruling against transgender Americans in United States v. Skrmetti. The case, which challenged whether transgender people have a constitutional right to access gender-affirming care, raised critical questions around sex discrimination, equal protection, and medical freedom. Rather than address those questions head-on, the Court dismissed them entirely. Instead, they leaned on a strained reading of equal protection that echoes the arguments that the State of Virginia once used to defend its interracial marriage ban in Loving v. Virginia, a parallel the liberal justices forcefully highlighted in dissent. The decision now threatens to reverberate far beyond transgender rights and opens the door to future rollbacks for women, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized groups.

Discrimination Disguised as Neutrality

Over the last four years, 25 states have banned gender-affirming care for transgender youth. Following best practices and supported by every major medical organization in the US and many abroad, this care has consistently helped trans youth thrive by sharply reducing suicidality, depression, and anxiety and offering a path to a relatively normal life. As the bans have wound their way through the courts, parents and patients have argued that they unconstitutionally target trans youth by banning treatments that remain fully legal for their cisgender peers.

Essentially, the argument presented to the Supreme Court was that the Constitution's equal protection clause requires heightened scrutiny for laws that target people based on sex or transgender status. When a state allows a cisgender girl to take testosterone blockers to treat facial hair growth because it causes her distress but denies that same medication to a transgender girl for the same reason, the transgender girl is not receiving equal protection under the law. Likewise, when a cisgender boy can undergo breast reduction surgery but a transgender boy cannot, the discrimination on the basis of sex and transgender status becomes undeniable.

The Tennessee law at the center of the case may go further than any other in making clear that it hinges on a classification based on sex. The law explicitly states that its purpose is to "encourage minors to appreciate their sex." Such a classification doesn't automatically invalidate the law, but it should trigger heightened scrutiny and require the state to prove that the law serves an important government interest and is narrowly tailored to achieve that goal. "Yet the majority inexplicably refuses to take even the modest step of requiring Tennessee to show its work before the lower courts," Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent.

The Supreme Court majority, however, had other ideas. Rather than seriously contend with the equal protection arguments, the justices sidestepped them entirely by claiming the law did not discriminate based on sex or transgender status but instead targeted the medical diagnosis of "gender dysphoria." The majority further argued that both cisgender and transgender people are equally prohibited from accessing medications for gender dysphoria—a tortured rationale that does not consider transgender and cisgender people equally. In this case, gender dysphoria serves as a thinly veiled proxy for transgender status, and the claim of equal treatment recalls the legal gymnastics once used to justify bans on interracial marriage and same-sex relationships. The reintroduction of this reasoning into Supreme Court precedent could open the door to broader rollbacks of rights for other marginalized groups.

An Old Argument

In their minority opinion, the liberal justices compare the ruling to Virginia's argument in Loving v. Virginia (1967), a landmark case about interracial marriage. "But nearly every discriminatory law is susceptible to a similarly race- or sex-neutral characterization. A prohibition on interracial marriage, for example, allows no person to marry someone outside of her race, while allowing persons of any race to marry within their races," said Justice Sotomayor.

Similar reasoning was once used to deny gay people the right to marry. Opponents of marriage equality argued that anti-gay marriage laws didn't discriminate because gay people, like straight people, had the same right to marry someone of the opposite sex. In the 1974 case Singer v. Hara, a court sided with the state's argument that "all same-sex marriages are deemed illegal by the state," and therefore claimed there was no violation so long as marriage licenses were denied equally to both male and female couples.

Fights over supposedly neutral laws that actually target protected characteristics have long played out across issues from housing discrimination to gerrymandering to employment law. Now, the Supreme Court is signaling that states can sidestep constitutional protections simply by crafting an ostensibly neutral workaround. As long as lawmakers can offer a vaguely plausible proxy—whether it's "gender dysphoria" or another euphemism—the Court appears willing to give them broad leeway to pass and enforce discriminatory legislation.

A Dangerous Precedent Expands

These archaic arguments and rulings take on new relevance in the wake of the Skrmetti decision as the court has effectively resurrected them to sidestep protections for transgender people. It's not just a legal loophole—it's now Supreme Court precedent, and one that could jeopardize a wide range of rights. The threat is compounded by the majority's reliance on another case—Geduldig v. Aiello (1974)—a precedent that has gained disturbing traction in recent Supreme Court rulings, most notably in Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), where it helped lay the groundwork for overturning Roe v. Wade (1973).

Geduldig held that denying disability insurance to pregnant women forced to stop working was not a violation of equal protection. To reach that conclusion, the court had to address the obvious: pregnancy is inextricably linked to sex and should trigger heightened scrutiny. Instead, the justices carved out a legal fiction—declaring that although pregnancy is related to sex, it is merely a "physical condition," and thus discrimination on its basis was not sex discrimination. Now, for the first time, the precedent has been expanded beyond pregnancy.

To say the Geduldig precedent has been controversial would be an understatement. Liberal justices have repeatedly contended that it was wrongly decided and serves to define what counts as sex discrimination so narrowly as to fit on the head of a pin. "That the Court today extends Geduldig's logic for the first time beyond pregnancy and abortion is more troubling still. Divorced from its fact-specific context, Geduldig's reasoning may well suggest that a law depriving all individuals who 'have ever, or may someday, menstruate' of access to health insurance would be sex neutral merely because not all women menstruate," reads Sotomayor's minority opinion.

In an era marked by the erosion of fundamental rights—from abortion access to transgender healthcare—the Supreme Court has now sanctioned legal arguments once relegated to the fringe. These rationales, revived and legitimized, have already gutted protections for trans people and those seeking reproductive care. But the implications don't stop there. This legal reasoning could open the door to renewed attacks on marriage equality, medical autonomy, and protections against gender discrimination. The Skrmetti ruling is not an isolated strike—it's a spark in a broader conflagration and is aimed at torching the legal scaffolding of equality itself.

Erin Reed (she/her) is a transgender journalist based in Washington, DC. She tracks LGBTQ+ legislation around the United States for her subscription newsletter, ErinInTheMorning.com.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.