Gerrymandering and Democracy: An Introduction

In the United States, most legislative districts must contain equivalent populations. But unfair district maps can still be drawn while maintaining an equal number of residents per district. The practice of drawing these unfair maps is called gerrymandering. In most cases, it’s entirely legal, but voters have the power to change that.

Gerrymandering has a long history in the United States (the word dates back to 1812). However, advances in sophisticated mapping technology and growing political segregation have made it increasingly easy for politicians to gerrymander for partisan advantage.

How Gerrymandering Works

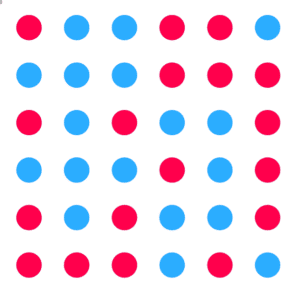

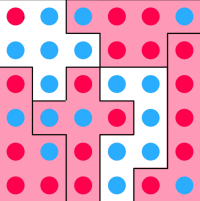

To illustrate, we will look at a theoretical population with 36 voters. The area is evenly split between the Blue Party and the Red Party.

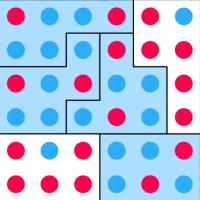

If we were to split this into six districts, we could easily draw the lines to advantage either party.

Two Red districts, four Blue districts.

Blue Party wins.

Four Red districts, Two Blue districts.

Red Party wins.

The basic strategy of gerrymandering is known as “packing” and “cracking.” District boundaries are drawn around as many opponents as possible to pack them into a few districts that they will win overwhelmingly. Concentrating the opponent’s votes into a few districts then leaves fewer of that party’s voters left, and those remaining voters can be “cracked” across the districts, where they will almost always be in the minority.

Gerrymandering in Ohio

Gerrymandering can be seen in practice in Ohio, the home state of the Kettering Foundation. Under current state law, redistricting decisions are made by a commission mostly made up by elected and appointed Republicans. In 2022, Ohio’s Supreme Court repeatedly rejected the commission’s maps for violating a provision of the state constitution that prohibits any map that was “drawn primarily to favor or disfavor a political party.” Ultimately, a federal court intervened, saying the fight over redistricting put Ohioans’ right to vote in that year’s election at risk. The federal court then mandated the use of one of the maps that the state supreme court had previously declared unconstitutional.

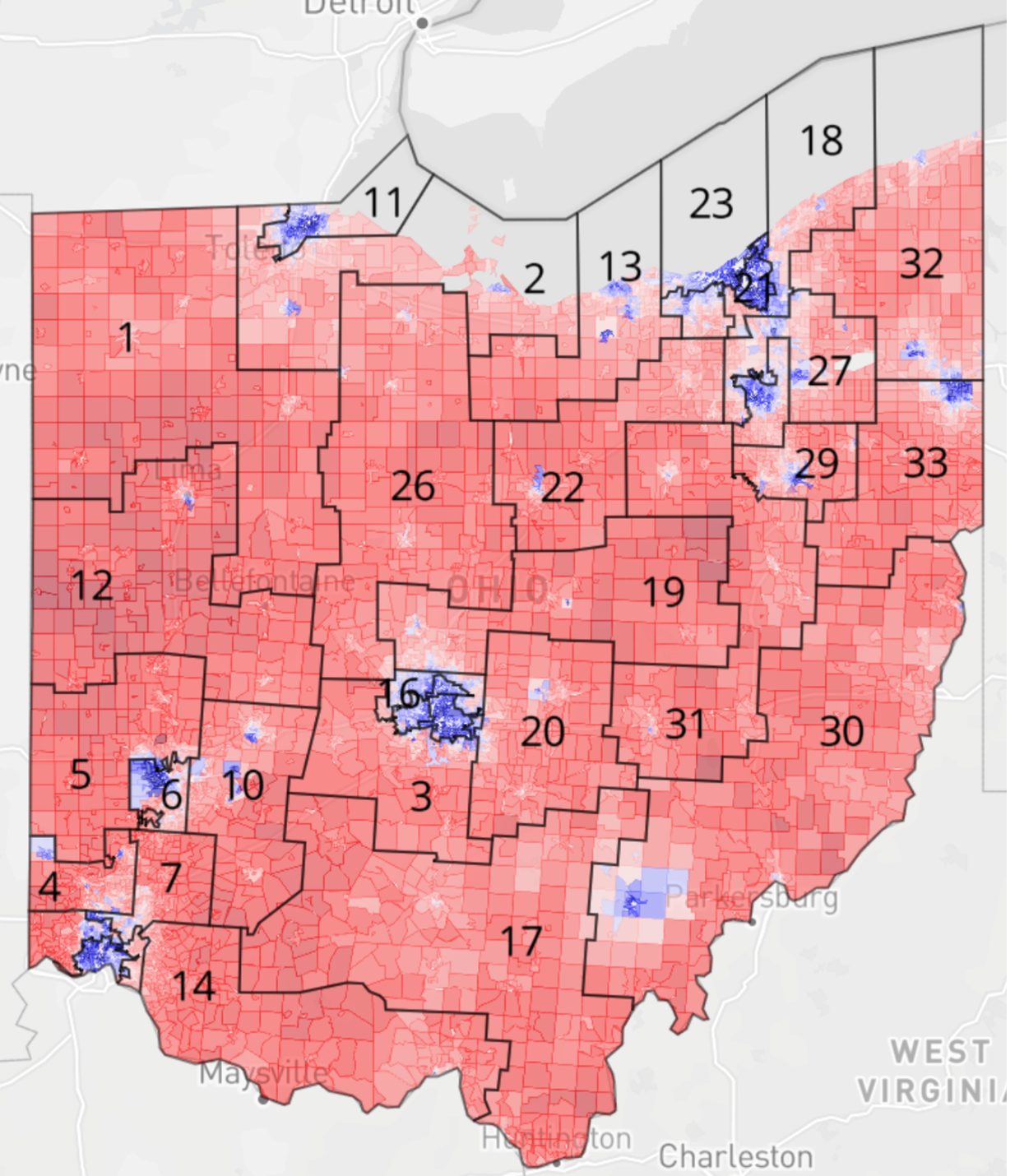

Ohio Senate Map

Map by Dave’s Redistricting using data from Voting and Election Science Team and Redistricting Data Hub.

Ohio’s current senate map includes many jagged, irregular shapes. The Ohio maps reproduced in this article also include data about the partisan lean of voting precincts, based on recent elections.

In the theoretical examples used earlier, each voter occupied the same geographical footprint. But in real life, some areas are more densely populated than others. Many of the blue dots on the Ohio maps represent cities that are more Democratic-leaning and more dense than other areas of the state.

Americans tend to live in politically like-minded communities, so it is difficult for even the most politically neutral map-drawers to create competitive districts that reflect the proportion of voters who support each party. This geography provides gerrymandering opportunities for less fair-minded redistricting officials.

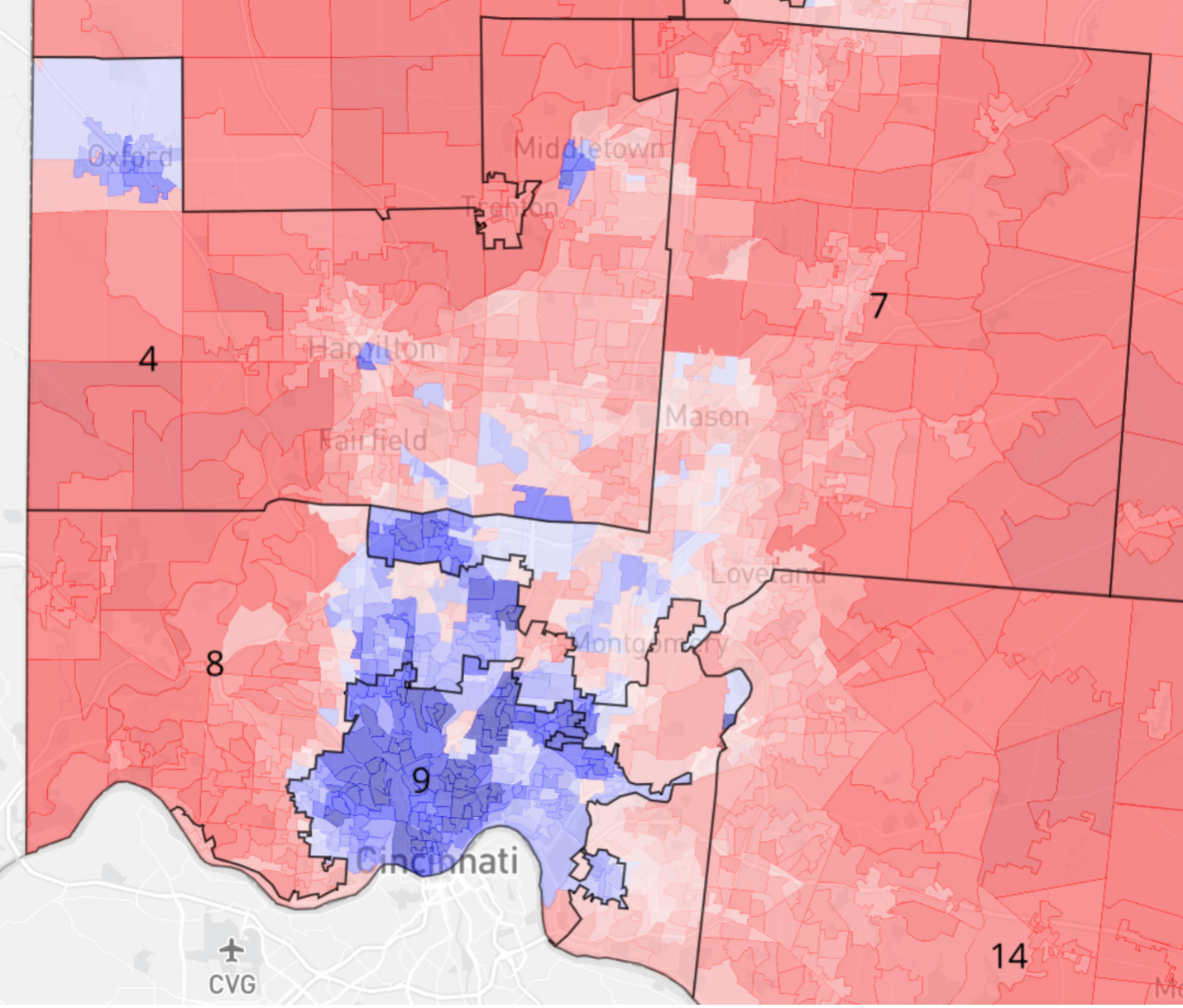

Cincinnati, Ohio Senate Map

Map by Dave’s Redistricting using data from Voting and Election Science Team and Redistricting Data Hub.

The districts around Cincinnati show real-world examples of packing and cracking. As you can see, the 9th district has been drawn to include Democratic-leaning areas near the city center. Democrat Catherine Ingram won nearly 73% of votes in this district in 2022. But other Democratic-leaning areas have been split across three additional districts: the 4th, 7th, and 8th. Each of these districts elected a Republican with approximately 60% of the vote in their most recent elections—a comfortable margin of victory without many wasted votes. (The above map has been updated for the 2024 election, so the results mentioned above are from previous but similar gerrymanders.)

Effects of Gerrymandering

The most significant effect of gerrymandering is that it distorts representation. In 2020, 53% of Ohio voters supported the Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, and 45% supported the Democratic candidate, Joe Biden. But in the US Congress and in Ohio’s State House, 67% of Ohio’s representatives are Republican and only 33% are Democrat. The state senate has an even larger bias at 79% Republican and only 21% Democrat.

Gerrymandering has contributed to a long-term decline in the number of competitive elections for the US House. According to the Cook Political Report, only 16% of US House seats are competitive. This means that for 84% of Americans, partisan representation in Congress was effectively decided when the maps were drawn, and our voting power is diminished.

When legislators don’t fear competition from the other major party, they have little reason to seek compromise or to represent moderate views. In fact, extremism can be a pragmatic response to the threat of challengers within their own party. And less competition means less scrutiny and more opportunities for corruption. “Safe” seats are unsafe for democracy.

A Pathway to Fair Maps

National legislation could address gerrymandering across the country and ensure an even playing field across all states. Federal legislators have introduced gerrymandering reform bills in recent years, but none have passed into law. In 2021, the For the People Act included provisions to prevent gerrymandering and had majority support in the House, but it was killed in a Senate filibuster. (Due to unequal representation, the 50 senators who supported the filibuster represented 41 million fewer Americans than the 50 Senators who voted to consider the bill, a related but different problem than gerrymandering.) The Supreme Court has also declared that it will not intervene to prevent partisan gerrymandering.

While attempts to prevent gerrymandering have stalled out in national government, there are success stories at state-level government. Each state controls its own redistricting process. Most often, the state legislature approves maps, but courts and redistricting commissions can also play a role. Nine states currently redistrict through independent commissions whose members cannot be elected officials of either major party. Many of these commissions are relatively new, arising from citizen activism and approved through ballot initiatives in recent decades.

Independent commissions have a strong track record of creating fairer maps, but they may not be enough to solve the problem of gerrymandering at the national scale. For one thing, partisan politicians don’t always give up power willingly. This year, Ohio voters will have the option to approve an amendment to the state constitution that would create a new independent commission, but politicians have inserted misleading language about the proposal onto the ballot. And only about half of states allow the kind of citizen initiatives that have been used to pursue redistricting reform in Ohio and other states.

Any solution to gerrymandering will require public awareness, advocacy, and activism. To understand how gerrymandering affects your own representation, the first step is to understand how district maps are drawn in your state. Nonpartisan resources, like the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, help to evaluate the fairness of state maps. Gerrymandering is a solvable problem but solving it will require informed and engaged citizens.

Alex Lovit is a senior program officer and historian at the Kettering Foundation. He is the host and executive producer of the Kettering Foundation podcast The Context.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.