Inclusive Populism: How to Defend Democracy Without Defending Broken Institutions

The MAGA movement has long positioned Donald Trump’s words and actions as being the authentic expression of “the will of the people” in an attempt to legitimate his unconstitutional actions and to position his critics as out-of-touch elites. This creates a strategic quandary for Trump’s opponents: to check his power, they must defend the institutions that they know are flawed. If populism stands broadly for a politics that speaks for the people against elites, perhaps another kind of populism is needed to help the pro-democracy opposition contest Trump’s claim that he speaks for the people. A new vision of “the people” can be offered to embrace the diversity and equality of a large and complex society without taking the side of the flawed institutions that made Trump’s presidency possible.

Populism: Anti-Elite, Not Anti-Diversity

A pro-democracy coalition can tap into some aspects of Trump’s style of politics without accepting his particular version of populism. Researchers tend to see populism as a style of politics that is compatible with almost any policy or ideology so long as politics is framed as a battle between a virtuous people who deserve to have the final say and corrupt elites who have usurped their power.

This minimal definition of populism only gets us so far, since pitting people against elites is a common feature of politics in any polity that incorporates some form of political equality, like liberal democracies. But populism is often accompanied by other pernicious traits, including xenophobia and viewing “the people” as a homogeneous unity. Indeed, even as the Trump administration shed some of its populist aura by delegating spectacular power to an unaccountable billionaire, these exclusionary traits endured and even intensified. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill cut Medicaid and SNAP benefits while allocating an unprecedented $170 billion to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to conduct mass deportations and build detention facilities. This might seem surprising since Trump’s return to the presidency was made possible in part by support from voters of color, who have now expressed disapproval of these policies. But it becomes more comprehensible when we understand the connection between right-wing populism and a homogenizing, exclusionary view of the people.

All forms of populism claim to represent the people as a key part of their politics, but how they claim to represent the people—that is, what kinds of representative claims they make—makes a big difference. Crucially, right-wing populists tend to make representative claims that rely on an antipluralist logic that identifies “the people” on the basis of their similarity. Being different is a sign that a person does not authentically belong. Indeed, right-wing populists see political equality as requiring homogeneity. According to this ideology, elites aren’t like us and so they have no right to rule, while others who are different and inferior don’t deserve to have a voice at all. Only the “real” people deserve to be treated as equals.

Who Are “The People”?

Now, the sense in which the people are alike can be strategically amorphous. Despite Trump’s frequent racist remarks, he was still able to win the support of voters of color who saw themselves as members of the people on the basis of some other similarity, whether that was a shared embrace of traditional gender hierarchies, associating as a hard worker opposed to freeloaders, belief in Christian nationalism, or some other indicator of one’s common status. But once returned to power, much of the Trump administration showed that their own view of the people is racially grounded, as made clear by policies like allowing only White refugees in the US. Vice President Vance has been an outspoken defender of xenophobia and racial exclusion, as when spreading racist lies about Haitian residents of Springfield, Ohio. Vance argued it was “totally reasonable and acceptable” not to want to have immigrants as neighbors and even sought to provide theological justification to sanctify this discrimination. Trump’s campaign rhetoric and effectiveness as an entertainer allowed others to see what they wanted in his vision of the people. However, the specifics of his vision have become impossible to ignore when backed by the power of office and embodied in concrete policies.

Opponents of Trump can see an opportunity here to position themselves as the better populists—as more authentically working class, for example—and so better able to fight economic elites. But simply offering a new basis of similarity is not enough. The problem is the antipluralist image of the people. Any politics that relies on claims of similarity can always easily slide into xenophobia. Historically, many populist movements have done so. The 1892 platform of the People’s Party (Populist Party), which gave populism its name, decried “the present system, which opens our ports to the pauper and criminal classes of the world.” In the context of a nation shaped by white supremacy and colonialism, certain forms of difference can be readily scapegoated; immigrants who do not yet share citizenship with the people can always be marked as different. Offering a genuinely inclusive form of populism requires not just changing the kind of similarity that binds a homogeneous people together but also changing the logic of the representative claim itself.

A Logic of Inclusive Populism

An inclusive representative claim would not be antipluralist; it would make equality and difference compatible. In other words, what makes us a people is not our homogeneity; we can be equal and different. On Trump’s representative logic, that’s impossible; asking to be different and equal looks like a demand for special treatment, which produces resentment. But for an inclusive populism, difference and equality go together because the pluralism of the people cannot be eliminated. We can see this logic at work in the speech Zohran Mamdani gave on his inauguration as mayor of New York City in which he vowed to lead a city “where government looks and lives like the people it represents” by which he meant that it is a city indelibly marked by difference. “Where else can you hear the sound of the steelpan, savor the smell of sancocho, and pay $9 for coffee on the same block? Where else could a Muslim kid like me grow up eating bagels and lox every Sunday?” he asked. As Mamdani’s second rhetorical question suggests, being marked as different oneself might make one an especially apt representative of the people. If xenophobia poses an obstacle to equality and wrongly divides the people, then an immigrant can be an especially apt representative of the people as a whole.

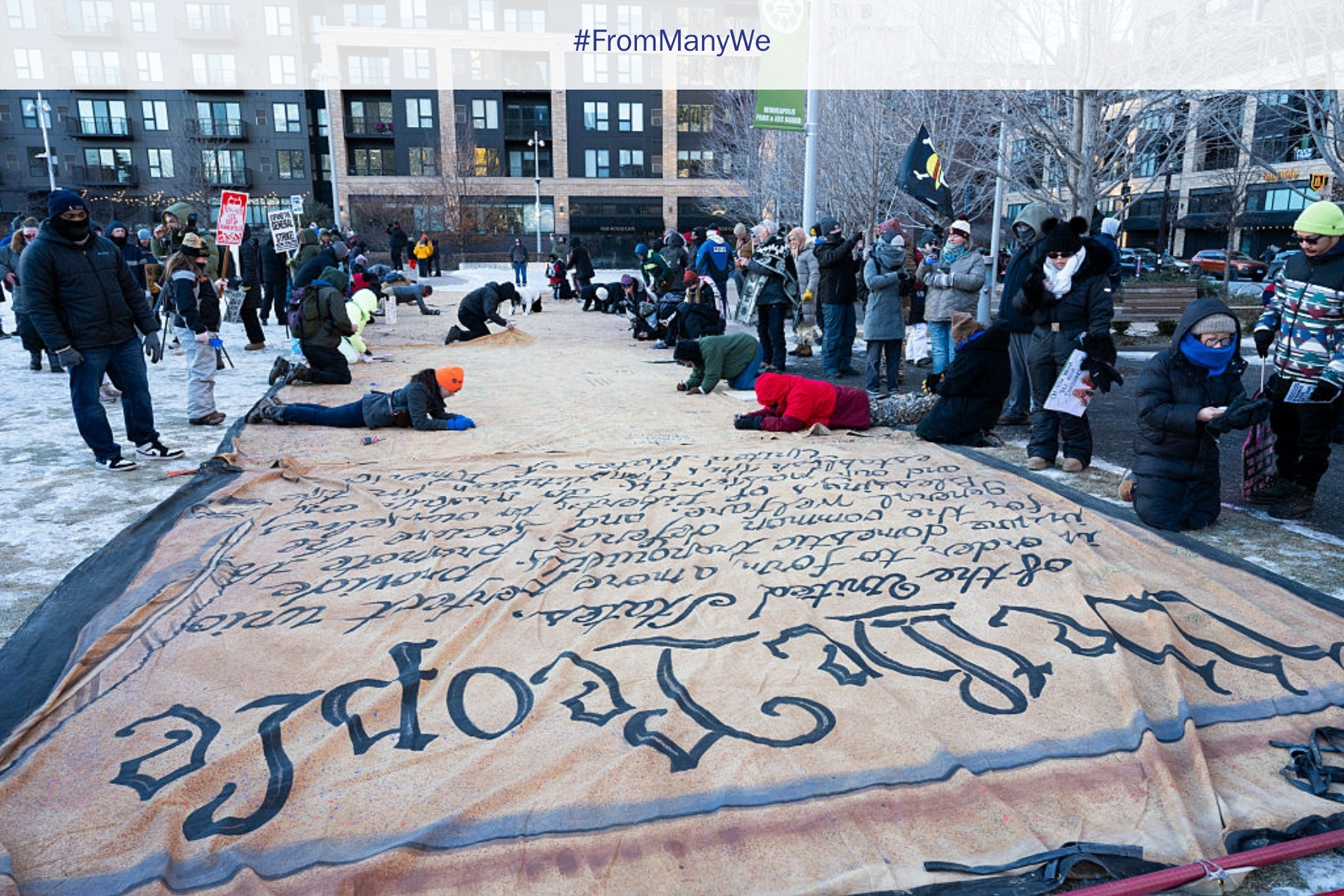

Today the boundaries and character of the American people—what it means to be part of the American people and who is allowed to belong—is a central struggle in national politics. On the first day of Trump’s second term, he issued an executive order called “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship” that purported to end birthright citizenship. As his second year in office commences, the administration is reportedly setting quotas to denaturalize thousands of citizens each month.

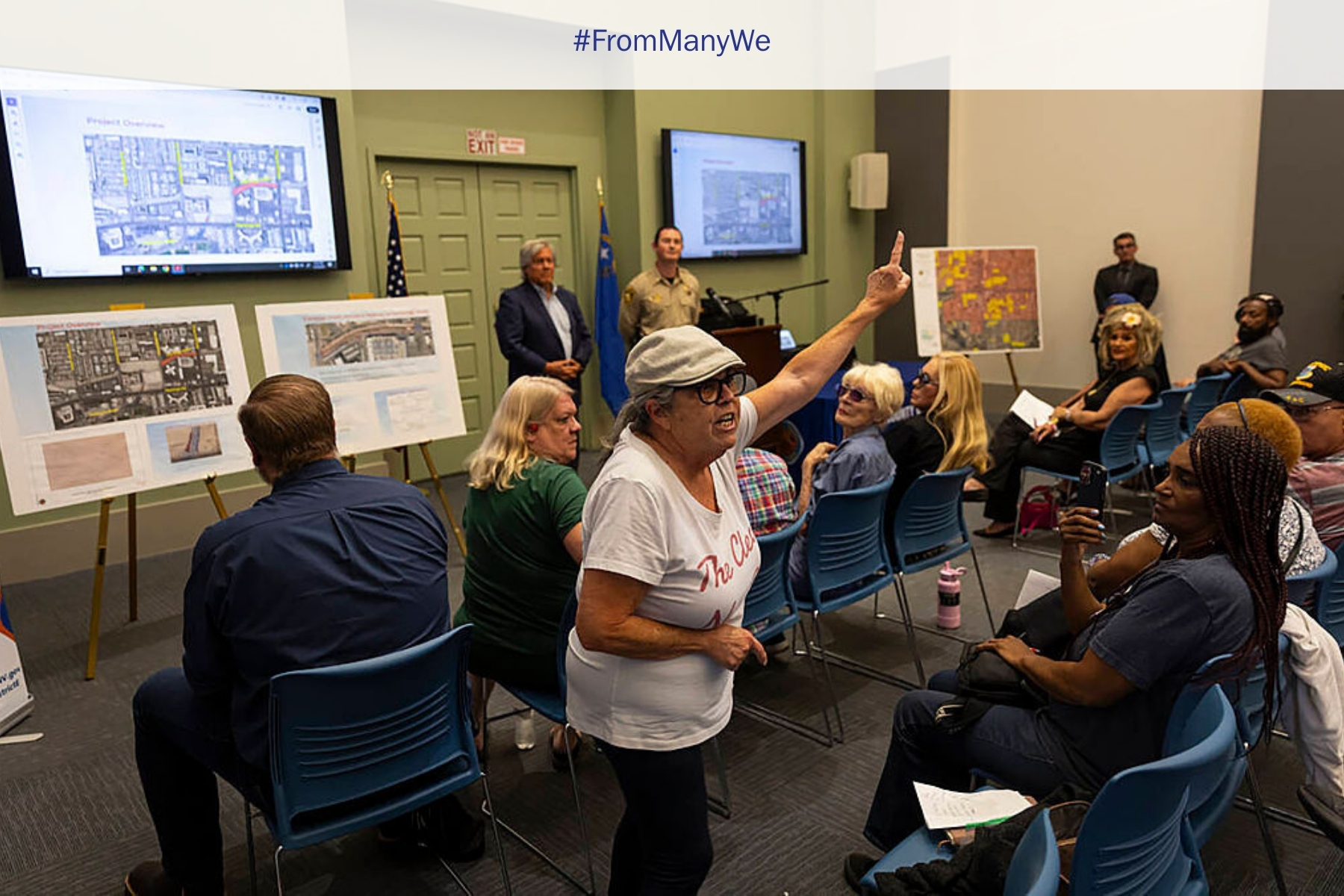

Those who want to resist Trump’s exclusionary concept of the American people can draw some lessons from inclusive populism without regarding it as a silver bullet. Popular opposition to Trump has coalesced around #NoKings protests, but these protests are often framed by a concern for liberal democratic principles rather than around specific claims on behalf of the common man. Consequently, these protests are rarely described as “populist.” While these protests have been very large and impressively dispersed all over the country, they are also notably narrow in the slice of the population they have mobilized, which has been disproportionately older, White, and more educated than the country as a whole. This opposition might be able to broaden their appeal by modeling their own representative claim on the populist Rainbow Coalitions assembled by Fred Hampton in the 1960s and by Jesse Jackson in the 1980s or even draw on the legacy of Reconstruction making explicit that they seek to represent a diverse people. Affirming that we are all equal and different can offer a real alternative to the vision of the people being used to legitimate unconstitutional actions without requiring a defense of a flawed status quo. There’s no guarantee that a voice centered on inclusive populism will win a political struggle against Trump and his political movement. But explicitly rejecting the homogeneity underlying his politics would at least move the fight from the opponent’s preferred terrain.

Benjamin L. McKean is an associate professor of political science at The Ohio State University. His research focuses on populism, global justice, and climate change.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.