Leveraging Data Resources for Civic Organizing

In a recent assessment of the state of democracy in the United States, researchers report the nation has moved from being a “full democracy” to being an “illiberal or mixed democracy.” In particular, they find declines in “toleration of peaceful protest, not using government agencies to punish political opponents, and fair electoral district boundaries.”

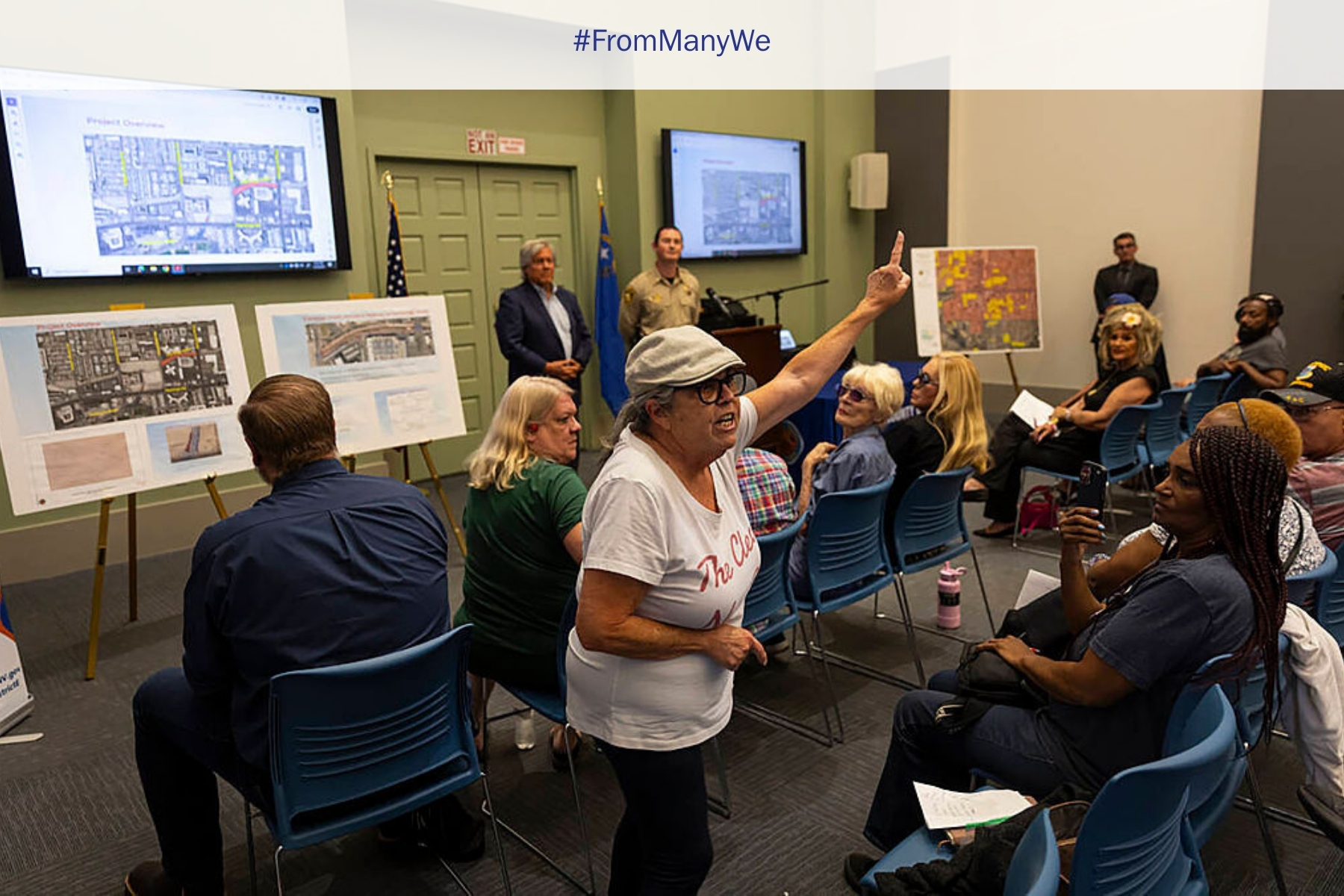

As leaders across various branches of government undermine the guardrails around various democratic norms, scholars and civic leaders are considering where and how to respond. The scale of the challenges facing Americans committed to a pluralistic, democratic society are national and global. However, responding to attacks on democracy does not need to be limited to a national or global scale. Researchers and movement leaders remind us that citizens and organizations can engage in some of the most influential work in defense of democracy at local and community levels.

Local Resistance Makes a Difference

Daniel Tirrell, cofounder and coexecutive director of The Ohio Democracy Project, writes how focusing on local issues and programs, even when the primary threats are national or global, led to effective results in Honduras, Ukraine, and Colombia. Acting locally builds resources and relationships and helps to make progress more tangible.

Guillermo Correa, a political scientist and the executive director of the Argentine Network for International Cooperation, also points to the importance of building civil society organizations. Doing so can bridge various levels of scope—local, regional, and global—where each level informs the other.

And as political scientist and Kettering Foundation research fellow Deva Woodly shares, changes in social media have encouraged large-scale mobilization but that mobilization has not translated into democratic organizing. Democratic organizing is about “bringing people into a community of action that serves as a space where they can build interpersonal connections, problem-solving capacity, and collective agency over time.” So, while investing in and building civil society is often neglected, it is essential for political action.

Resources Can Be Hard to Find

Given the importance of organizing and taking action at the local level, it is vital to know who is in our communities and what their needs might be. Some of us may know who our neighbors are and what resources exist in our communities, but others may be less sure. We are also living with an overabundance of information available to us at every moment. When considering which sources to trust, we also must determine if an algorithm has provided us with accurate information and resources that will meet our needs.

In my work codirecting the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), I consistently hear nonprofit directors, community members, and congregational leaders also voicing concerns about resources. They want to serve their neighbors, and they are searching for accurate information but can feel overwhelmed, particularly in a moment of national and global democratic backsliding.

A Tool for Dialogue and Inclusion

The Community Profile Builder (CPB), available for free on the ARDA website, is a resource that community and organizational leaders can use to instantly access demographic and religion data for any community in the United States. The CPB empowers users to map community assets, which the “asset-based community development” literature highlights as a first step in organizing. The initial map shows the locations of religious congregations in a chosen area using any zip code, city and state, or complete address.

After users choose an area, the CPB then gathers and displays the social, economic, and religious information about the selected community or neighborhood. The data sources include the United States Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, the US Religion Census collected by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies, and Data Axle USA.

In a series of training sessions filled with community leaders, nonprofit directors, and clergy, ARDA was able to introduce the CPB and then follow how users applied the data-rich snapshot of their respective communities. We found they appreciated knowing the religious organizations already present in their cities and towns. The CPB also signaled potential demographic groups that might benefit from focused attention.

For some users, it augmented planned outreach efforts. For instance, one Catholic priest participating in an ARDA workshop in Indianapolis was helping lead the Indianapolis Archdiocese’s education efforts. He was a part of ongoing conversations around whether his diocese needed to offer languages other than English, and if so, which ones. Some of the decision makers held assumptions—not based on any data—that the surrounding community members would be best served by offering Spanish. However, he was able to use the CPB to demonstrate that the diocesan schools’ assumptions around language needs were outdated. Many more folks from Southeast Asia were populating those communities, so a focus on Southeast Asian immigrant Catholics was necessary.

The insights from the CPB also proved useful to community and nonprofit leaders who were planning initiatives that focused on poverty, education, refugee resettlement, and interfaith dialogue. They used the CPB to look for possible partnerships with other religious congregations.

One of the most impactful reflections from our training sessions came from a mayor serving a city in northeast Indiana. He shared stories of how the political polarization present at the national level regularly infected local politics and his ability to bring groups together to solve issues in his city. However, when citizens in cities like his had access to trustworthy data to inform their conversations, the negative influence of political polarization was neutralized.

By resourcing high-quality data in conversations at the local level, we can help (re)build our civic spaces, develop resources and relationships, make progress more tangible, and increase our problem-solving capacity. The data provided by ARDA’s free CPB helps people see the assets and potential of their communities more clearly. Citizens and community leaders can then capitalize on the diverse perspectives that such voices and information can bring to the discussion, which can then lead to more fruitful and generative conversations.

We are living through a moment where the hallmarks of a pluralistic, democratic society are under direct threat from disinformation, authoritarianism, and polarization. While the scale of these challenges is global, social movement leaders and scholars remind us that thinking locally is vital. The communities using ARDA’s free CPB can build the durable connections that make the promise of democracy real for everyone, everywhere.

Andrew L. Whitehead is professor of sociology at Indiana University Indianapolis, codirector of the Association of Religion Data Archives, and a Charles F. Kettering Foundation Research Fellow. Follow him on Bluesky and Substack.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.