Liberating the Headlines: How Media Can Cover Aspiring Authoritarians without Enabling Them

In recent years, media ethicists have found little to praise in the way the American press covers political leaders, especially Donald Trump. Disingenuous leaders have used the news media to push false or misleading narratives by leveraging the thousands of headlines that run during a news cycle. Too often, in order to maintain the appearance of balance, editors have yielded their own framing power, often giving legitimacy to those who are subverting democracy.

Donald Trump has had unique leverage over the headline writers in newsrooms who have allowed his claims to dominate. But a sliver of good news has emerged, and signs are showing that newsrooms might be slowing their race to headline stories with everything Trump says and does. The press may be revealing a new willingness to reassert its agency in the face of authoritarian attempts to control the news cycle.

Tariffs or Liberation Day? A New Pattern

In the first week of April, Trump declared unilateral tariffs in a new executive order, which he called “Liberation Day.” This was a classic Donald Trump approach of using clever framing to try to unhinge the substance of a debate from the impression that the policy announcement could leave on people. A president is well within their right to name and frame their policies in their own language. The question was whether newsrooms would automatically let the words “liberation day” ride on their headlines despite there being no evidence about who was going to be liberated, when, and from what.

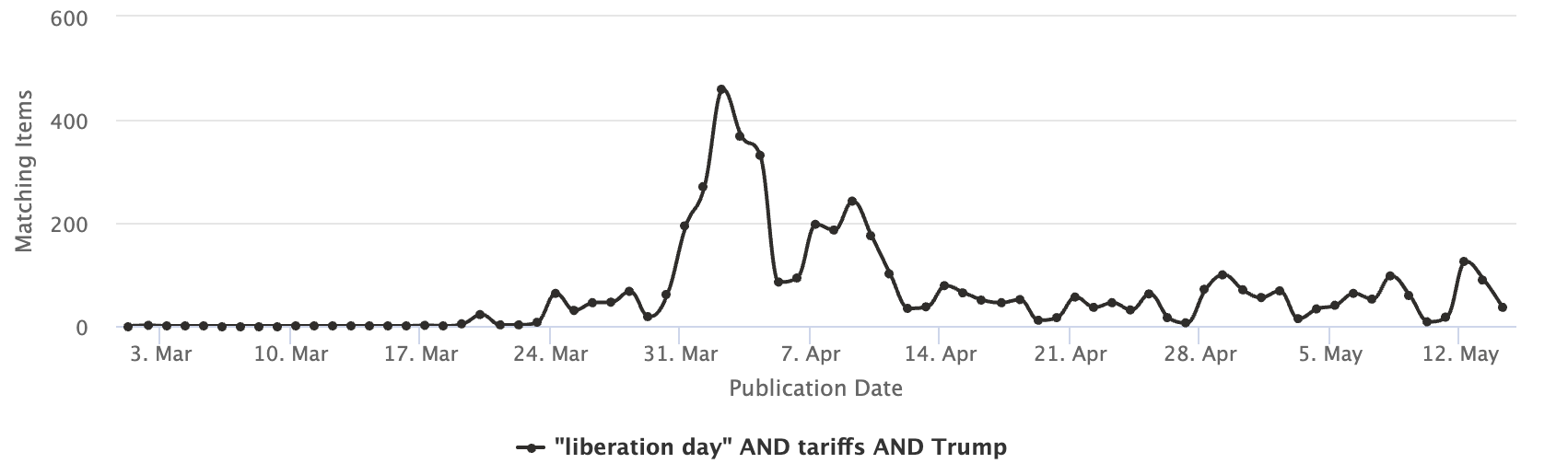

The research tool Media Cloud helps researchers sort and analyze news stories around timelines, both in the American sphere and globally. In a review of the tariffs coverage from March to May, the first two weeks of April tell the story of a media industry that has become more guarded in headlining.

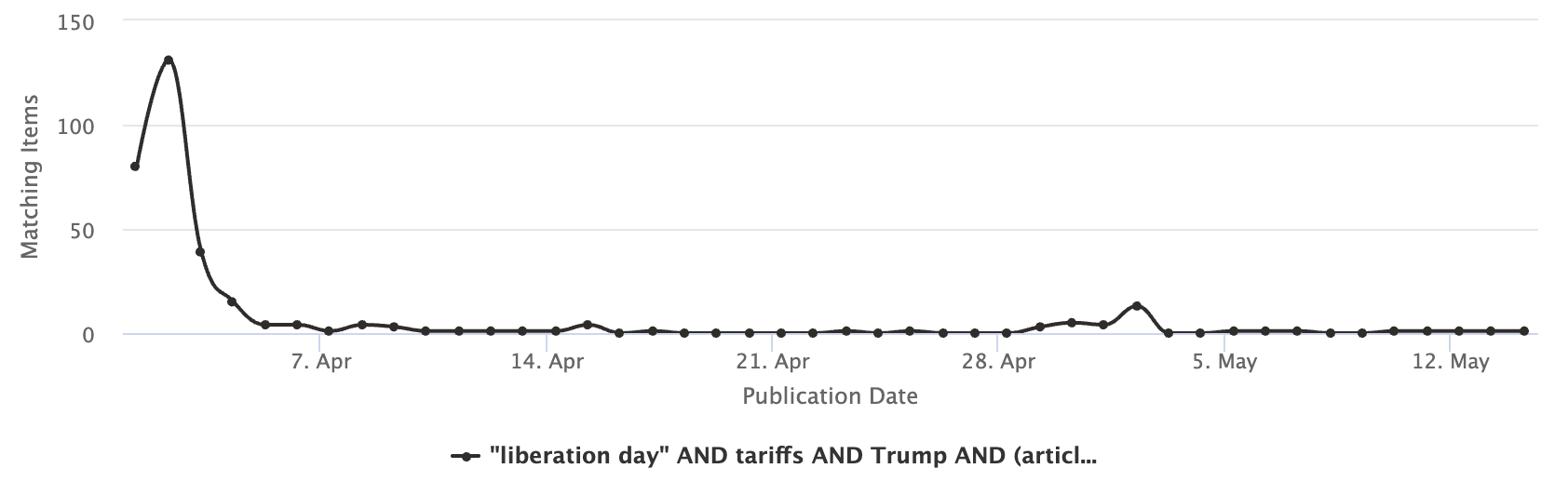

First, the story volume from March 1 to May 14 using the keywords “liberation day,” “tariffs,” and “Trump” show how Trump’s April 1 announcement on global tariffs expectedly created a news cycle, mainly because of how the markets reacted. I looked at results for a collection of 248 national US publishers, one of several publisher collections at Media Cloud. From the chart, you can see how the primary cycle lasted April 1 to roughly April 14. After that, coverage dies down to a lower beat through the weeks that followed.

The April tariffs news cycle. Donald Trump’s April 1 announcement on global tariffs expectedly created a news cycle. See the story timeline here between March 1 and May 14. The figure shows the primary cycle lasted from April 1 to roughly April 14.

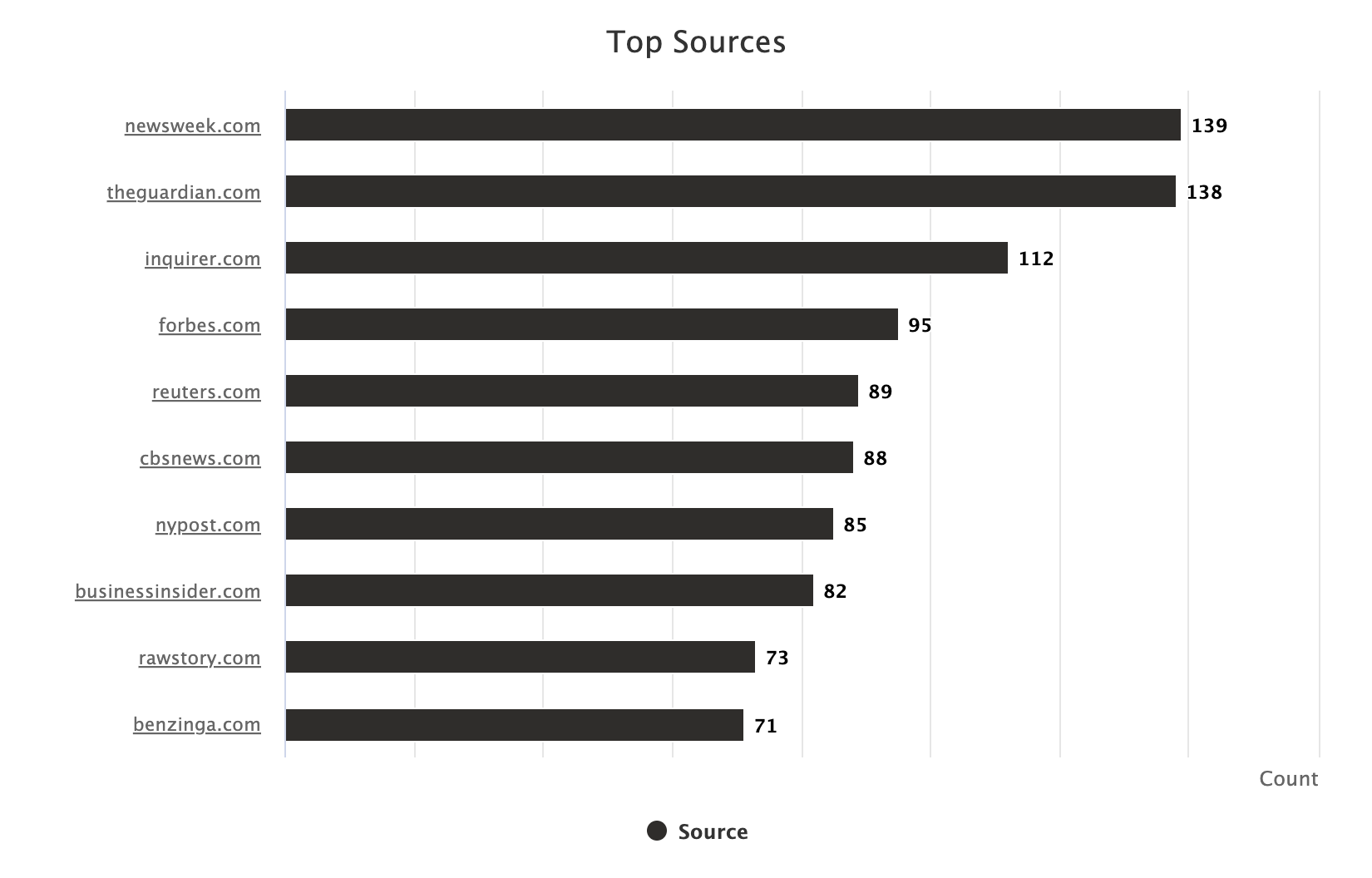

Next, when stories from the same publisher group are searched for from the exact time period of April 1–14 using the keywords "liberation day," "tariffs," and "Trump," a total of 2655 stories emerge. This number seems fair in terms of volume, particularly to researchers like myself who are familiar with the system.

Media Cloud results for search queries on “liberation day,” “tariffs,” and “Trump” in the body of stories as well as headlines, for April 1–14, 2025.

The pool of 2655 stories includes two groups. Group 1 used Trump's words "liberation day" in the headline. Using the term in the headline made the framing more visible since headlines tend to attract attention in news feeds as people scroll, whether they read the stories in full or not. Group 2 was made up of stories where this term was not in the headline, but the term was part of (necessary) reporting in the body. Roughly, only 11% (286) of the stories fell into Group 1. The rest were in Group 2.

The chart shows how headlines with the words “liberation day” had a small peak between April 1–14. The total was 286 stories, about 11% of the 2655 total stories that 248 US publishers posted during the same time.

Rather than simply amplify Trump's framing, the press used a variety of terms. This is certainly better than a counter-case: Imagine if a majority of the 2655 stories (say over 50% or 60%) had carried the words "liberation day" in the headline. The fact that this did not happen at scale is a sign of headlining restraint.

Compare the coverage with what happened in 2020. When asked by a journalist why African Americans were still dying at the hands of police, Trump said, "And so are White people. So are White people. What a terrible question to ask." He then added, "More White people, by the way. More White people." This resulted in a major news cycle. I don't have a Media Cloud comparison for that, but I documented this as a headline case by counting stories on news feeds. A stark majority of headlines carried his direct quotes instead of calling out his misleading framing. This case and its significance is documented in Guardrails for News Headlining: Principles and Workflow (see section 2, Centering Valid and Authentic Claims).

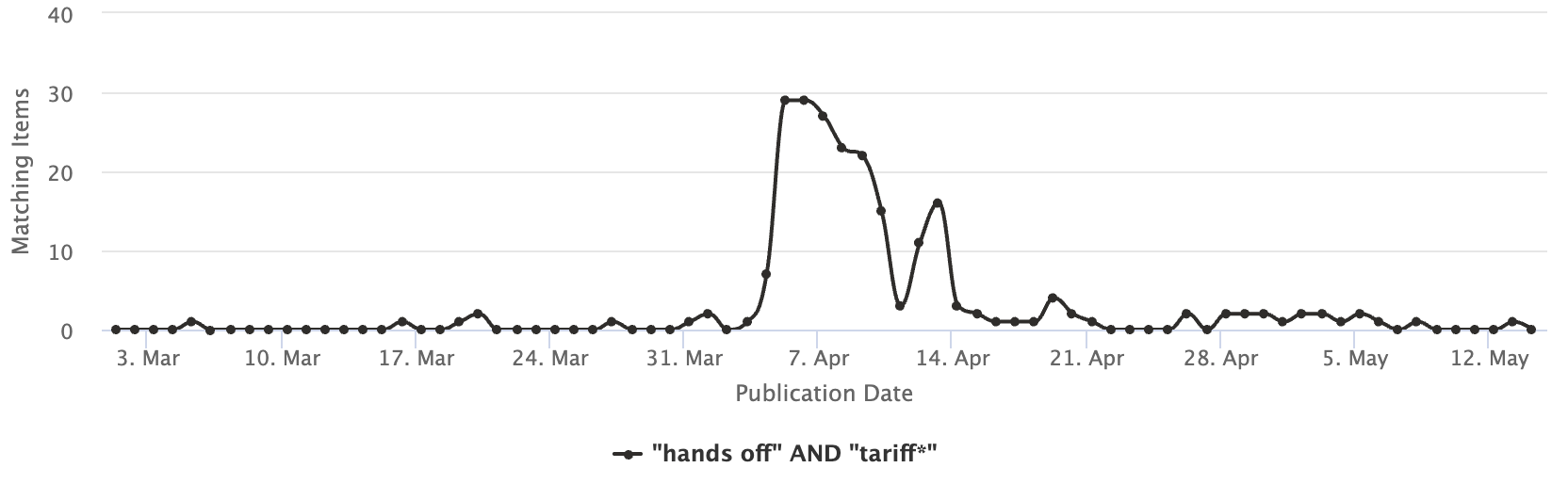

The news cycle on tariffs also coincided with a smaller one on the Hands Off protests. These demonstrations were held across the United States on April 5, 2025, to speak against a wide range of the Trump administration's policies. Three to five million people were estimated to have participated in these rallies. In all, 729 stories were published in the same time period of April 1–14 that referred to the Hands Off protests as a term while 188 stories referred to "tariffs." But a meager 23 stories intersected the terms "hands off" and "liberation day." But among these 23 stories, no stories used "liberation day" in the headline itself. This suggests that "liberation day" as a frame did not get (and likely did not merit) mention in the Hands Off protests coverage, another sign of journalistic pushback.

729 stories were published in the same time period of April 1–14 that referred to the Hands Off protests as a term. 188 stories intersected with “tariffs” and a meager 23 stories intersected the terms “hands off” and “liberation day.” Zero stories from this category had “liberation day” in the headline.

Framing Matters

Headlines on political stories are an important facet of public communication. Democracies cannot exist without communication, and the news media are a key part of the human communications infrastructure. Framing is a crucial tool in persuasive communications and is used by leaders everywhere. Headlining, because it is an act of creative brevity, requires deciding what gets saliency. Headlines are frames to view the story, its facts, and its findings themselves. A news editor has choices in deciding the headline. They could choose a leader’s plain claim, a key fact, a rhetorical flourish, or a synthesis of the realities in the story—any of these could make the headline.

When it comes to rhetorical claims or lies promoted by bad actors, newsrooms would do well to remember that leaders can drive disinformation and manipulate discourse. One source’s claims need not be automatically and uncritically accorded overarching framing power in news cycles, unless they have passed checks on authenticity and validity. It is up to editors to consider the totality of circumstances that the reporters have considered in the story itself, and the readers’ stakeholdership for the issues in the story before deciding the headline.

For our case at hand, the fact that only 11% of the stories during the peak news cycle of April 1–14 tariffs coverage carried Donald Trump’s “liberation day” framing is a promising insight. Headlining in mainline political coverage may be showing improvement and more journalistic independence compared to a few years ago. This is an important indication at a time of rising authoritarian and anti-democratic attacks on American institutions, including and especially the news media.

Images courtesy of: Hal Roberts et al. “Media Cloud: Massive Open Source Collection of Global News on the Open Web.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 15, no. 1 (2021): 1034–1045.

Subramaniam (Subbu) Vincent is director of the Journalism and Media Ethics program at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. He focuses on developing tools and frameworks to help advance new norms in journalism practice and ethical news distribution.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.