Nazis Burned Trans Books to Usher in Fascism: Now Trump Does the Same

This article was originally published at Erininthemorning.com. The author will be joining the foundation’s From Many, We series in the coming year.

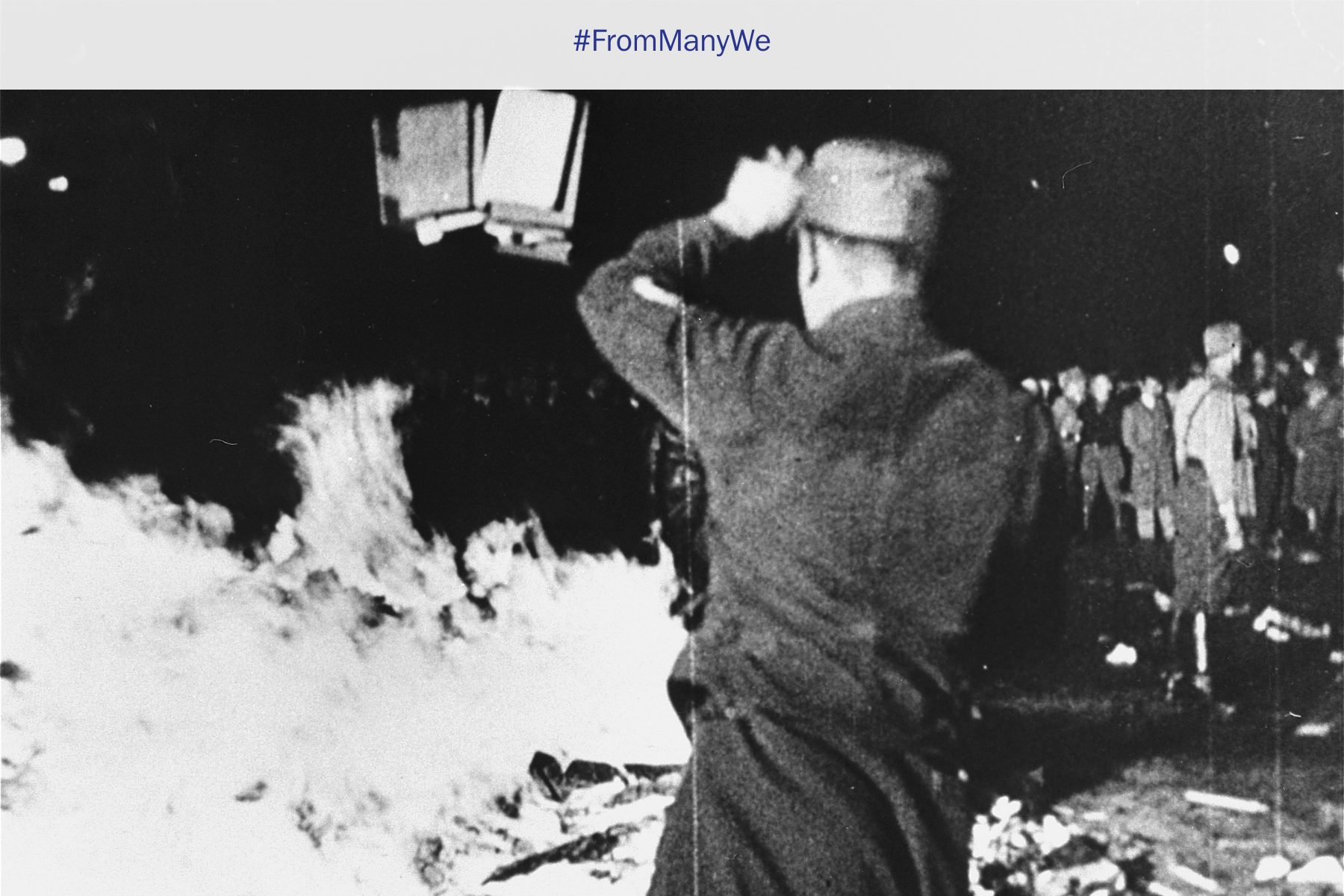

Nearly a century ago, Nazis raided the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft—the Institute of Sexology—a pioneering research institution and clinic founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, a forefather of transgender research. The institute housed tens of thousands of books, research notes, and data documenting the first decades of scientific study on transgender and queer people. Long before the labor camps and mass killings, the Nazis identified Hirschfeld as a primary enemy, targeting his work in the early rise of fascism. That night, in Berlin’s Bebelplatz Square, they burned his institute’s collection in a now-infamous spectacle, immortalized in history books yet often stripped of the context of who, exactly, was targeted. Now, President Trump is doing the same: digitally burning records of transgender people and pressuring nonprofits to follow suit.

And those digital fires have spread. Within days of Trump’s anti-trans executive orders, the word “transgender” was erased from nearly every government website where it once appeared. CDC data on transgender health was stripped from its pages. The Stonewall National Monument—dedicated to the LGBTQ+ people who fought back against oppression, led by transgender activists—was purged of any mention of transgender people online. Even institutions and nonprofits serving LGBTQ+ communities, particularly those receiving federal funding, have been pressured into scrubbing “transgender” and “gender identity” from their materials. The Nazis would envy the speed and efficiency with which it was done.

As a transgender journalist dedicated to documenting these events and helping people grasp the broader context of attacks on queer and trans communities, I feel the weight of this moment. The sacking of Hirschfeld’s institute was not met with uproar; there was little popular resistance. At the time, no journalists spoke with sympathy about those who sought care there—much less transgender journalists who might have needed that care themselves. If only alarm had spread then, or even earlier, when the very people receiving treatment at the institute were first being demonized.

And like today’s digital fires, those flames were not lit without years of prior hate. Four years before the book burnings, one of the earliest editions of Der Stürmer—the Nazi propaganda publication that fueled fascism’s rise—accused Hirschfeld of “grooming” youth, echoing today’s attacks on LGBTQ+ people. Hitler notoriously called Hirschfeld “the world’s most dangerous Jew.” Trans and queer people were the canaries in the coal mine of atrocity. Similarly, just a few years ago, the “groomer” slur ignited online, feeding a growing trans panic that has only escalated since.

I don’t know where we are heading as a country, or what future you see when you stare into today’s fires. But I do know that the transgender and queer readers I write for every day see the signs—and fear the worst. Trans people, in mass numbers, have rushed to secure passports—some too late, as the administration has tightened restrictions on gender marker changes, in some cases even confiscating documents. Anyone active in this space knows people who have already left. And yet, despite this fear, so many cisgender people I speak to—including journalists covering stories that implicate our rights—seem unaware of the full scope of what is happening. I even had one reporter recently express surprise and dismay at hearing trans people were removed from Stonewall, something widely reported on in recent weeks.

People should pay attention. Court battles are already raging, with rulings blocking the administration from stripping funding from hospitals that provide transgender care. In another case, a judge appears poised to halt Trump’s attempt to expel trans service members from the military. As Trump and his allies openly float the idea of ignoring court rulings, the risk of a brazen defiance of judicial authority looms, and transgender rights could be an early test case. The way this administration treats transgender people may foreshadow how it treats all those it seeks to silence—a potential step toward consolidating totalitarian power.

Trump’s digital erasure of transgender people is more than policy—it is a declaration that the very existence of certain human beings is unwelcome in the official record. This is not a hallmark of a democratic leader respecting courts and laws; it is the move of someone intent on atrocity. When you eliminate all traces of a people’s identity, it surpasses mere ideology and becomes an act of “salting the earth,” ensuring their name and their history cannot be seen. Such an action must be recognized and resisted by every voice capable of protest. We are witnessing the dark echo of “first they came for . . . ” in our own time, and we must understand that after they come for us transgender people, they will not simply stop with us.

Erin Reed (she/her) is a transgender journalist based in Washington, DC. She tracks LGBTQ+ legislation around the United States for her subscription newsletter, ErinInTheMorning.com.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

Photograph courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park. A member of the SA throws confiscated books into the bonfire during the public burning of “un-German” books on the Opernplatz in Berlin, May 10, 1933.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.