Grading Desegregation: Dayton Gets an Incomplete

Seventy years ago this month, the Supreme Court of the United States decided the case of Brown v. Board of Education. Most Americans recall that this was the decision that ended state-sanctioned segregation in American public schools. Desegregation has improved educational and social outcomes for many students, but it remains an incomplete project as evidenced by the history of Dayton, Ohio, a typical American city and the hometown of the Kettering Foundation.

Desegregation and Democracy

In his book, Children of the Dream, Rucker Johnson compares outcomes for students who attended segregated and desegregating schools in the 1960s and 1970s. He found that over the long term, Black students who attended integrated schools saw greater educational attainment, higher wages, and better health, all without significant negative effects for the White students attending these same schools. Decades after learning in integrated classrooms, adults report having more racial tolerance and more diverse friendships. These outcomes are important on their own terms, but integration in education is critical in an inclusive democracy in which all citizens have voice and feel they belong.

The Dayton Desegregation Story: Structural Challenges and Resistance

The 1970s desegregation story of Dayton is in many ways a typical story of attempts to integrate Northern districts in American public schools, but Dayton’s history has some unique elements. During this same period, the city was home to a racist serial murderer who terrorized Black residents in his quest to prevent school integration and other forms of race mixing. But on the whole, Dayton’s story is emblematic of America’s limited commitment to educational integration and equity.

Dayton’s Black population grew during the Great Migration of the mid-20th century; by 1960, Black Americans accounted for about a fifth of the city’s population. Discriminatory housing policies like “redlining” largely restricted Black Daytonians to a limited number of neighborhoods. School zones followed these lines, meaning that Black and White students mostly attended separate schools.

In 1971, the Dayton school board established an advisory committee to study desegregation. The committee recommended that the state consolidate the school districts of the city and its surrounding suburbs. A metropolitan-wide desegregation plan would be necessary to prevent White families from avoiding integration by moving to the suburbs. The advisory committee wrote, “There will be no place to run from the changes that must be made.”

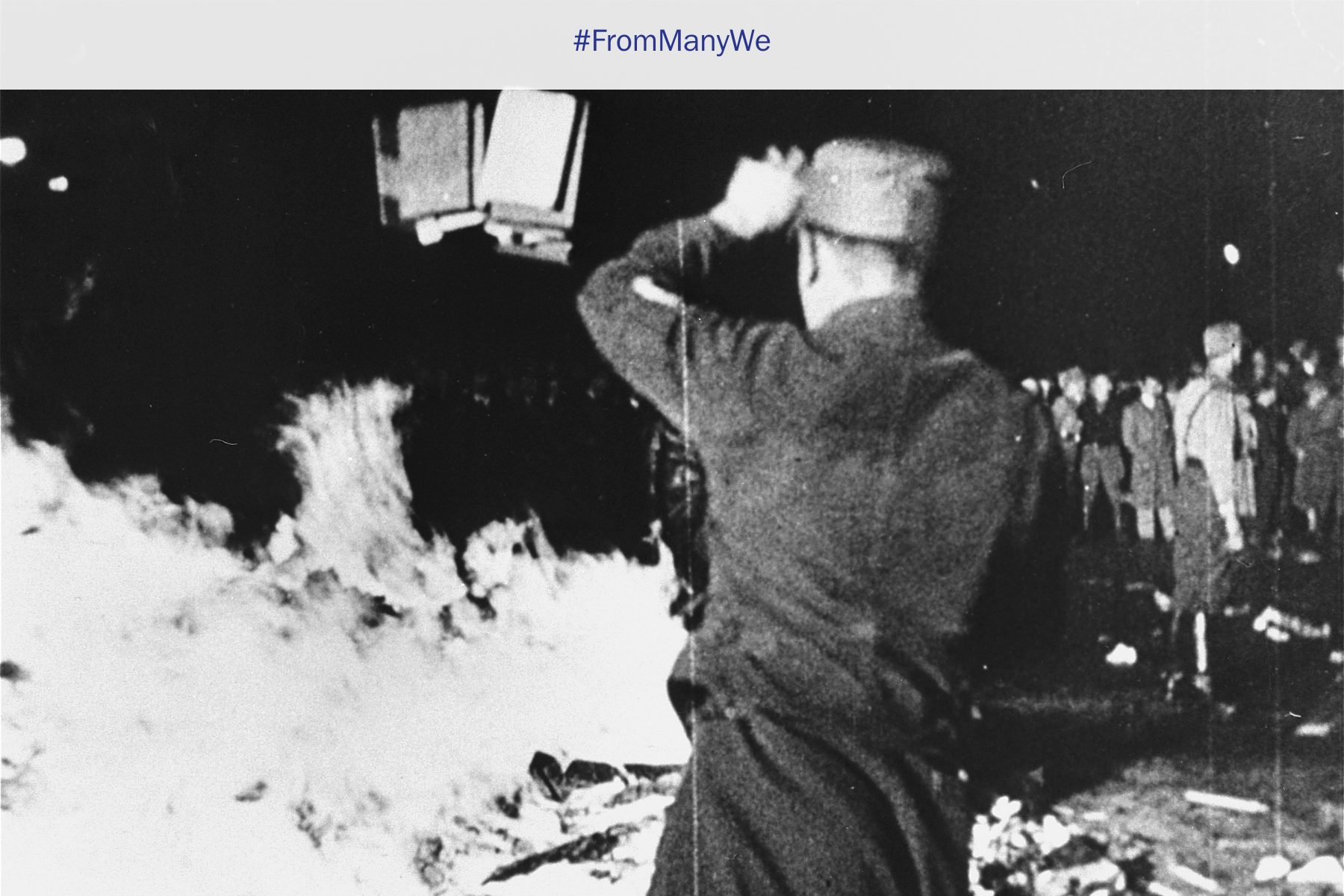

But later that same year, conservatives won majority control of the school board and rescinded the endorsement of desegregation. In 1972, the NAACP sued, seeking a desegregation plan across the entire metropolitan region. By 1976, when the lawsuit finally resulted in court-ordered desegregation, the increasingly conservative Supreme Court had already ruled, in Milliken v. Bradley, that desegregation plans should not include multiple school districts. Court-ordered desegregation in Dayton was limited to the city itself.

The first day of school under Dayton’s new desegregation plan, on September 2, 1976, was uneventful. Students were bused across town to ensure racial balance in each school. A quarter of the students stayed home on that first day. By the second day, attendance was above previous levels.

But restricting the desegregation plan to city limits had consequences. Between 1970 and 2010, while the city’s Black population held relatively steady, the White population was cut in half. Overall, the city’s population fell by more than 40 percent between 1970 and 2010. Some of this was due to a regional economic decline, but much of it was also due to out-migration to the suburbs. The metropolitan region’s population declined by a much more modest six percent over the same period. Avoiding racially integrated schools was not the only motivation for people to leave Dayton for the suburbs, but it was a significant factor.

By 2002, several state and local agencies, including the local chapter of the NAACP, signed an agreement ending the desegregation order in Dayton. By that point, 73 percent of students in Dayton Public Schools were Black. US District Court Judge Walter Rice, who oversaw the agreement, explained his decision: “There simply weren’t enough White children.”

21st Century Segregation

In effect, the Dayton region never desegregated its schools. Today, 78 percent of Dayton public school students identify as minority, and total enrollment is less than a quarter of what it was at the district’s pre-desegregation peak. The eight largest suburbs in the region have majority-White enrollment. According to Ohio School Report Cards, each of them has higher average teacher salaries, higher test scores, and a higher graduation rate. Prior to Brown, Dayton’s schools were segregated and unequal; they remain so today.

The Brown decision had real effects: ending formalized legal segregation in Southern states, increasing educational access for minority students in some cases, and contributing to cross-racial experiences and understanding. But commemorating Brown should not fool us into thinking that the goal of educational integration and equity has been achieved. Integrated, high-quality schools are essential for American democracy, but court orders are not going to build those schools on their own. If we believe in educational integration, we have to act—and vote—accordingly.

The Kettering Foundation is celebrating the anniversary of Brown:

LISTEN to The Context Podcast: Matthew Delmont: Brown v. Board–What it Achieved and Where it Feel Short

WATCH Education and Democracy: A Conversation with Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole

WATCH Kelley Robinson: Stand Up for the Promise of Brown v. Board of Education

READ in From Many, We Blog: Honoring Brown v. Board of Education: A National Opportunity to Confront Today’s Challenges

READ in From Many, We Blog: 70 Years After Brown: A Reflection on Democracy and Education

Alex Lovit is a senior program officer and historian at the Kettering Foundation. He is the host and executive producer of the Kettering Foundation podcast The Context.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.