Social Bots and the Frightening Unknowability of Social Media

In a classroom at UMass Amherst this fall, I saw the scariest thing I’d ever seen on the internet. It was a tweet that read, “I’m sorry, but I cannot comply with this request as it violates OpenAI’s Content Policy on generating harmful or inappropriate content.” For years, scholars have warned of a wave of AI disinformation, but this was the first hard evidence I had seen that artificial intelligence was being harnessed to disseminate disinformation.

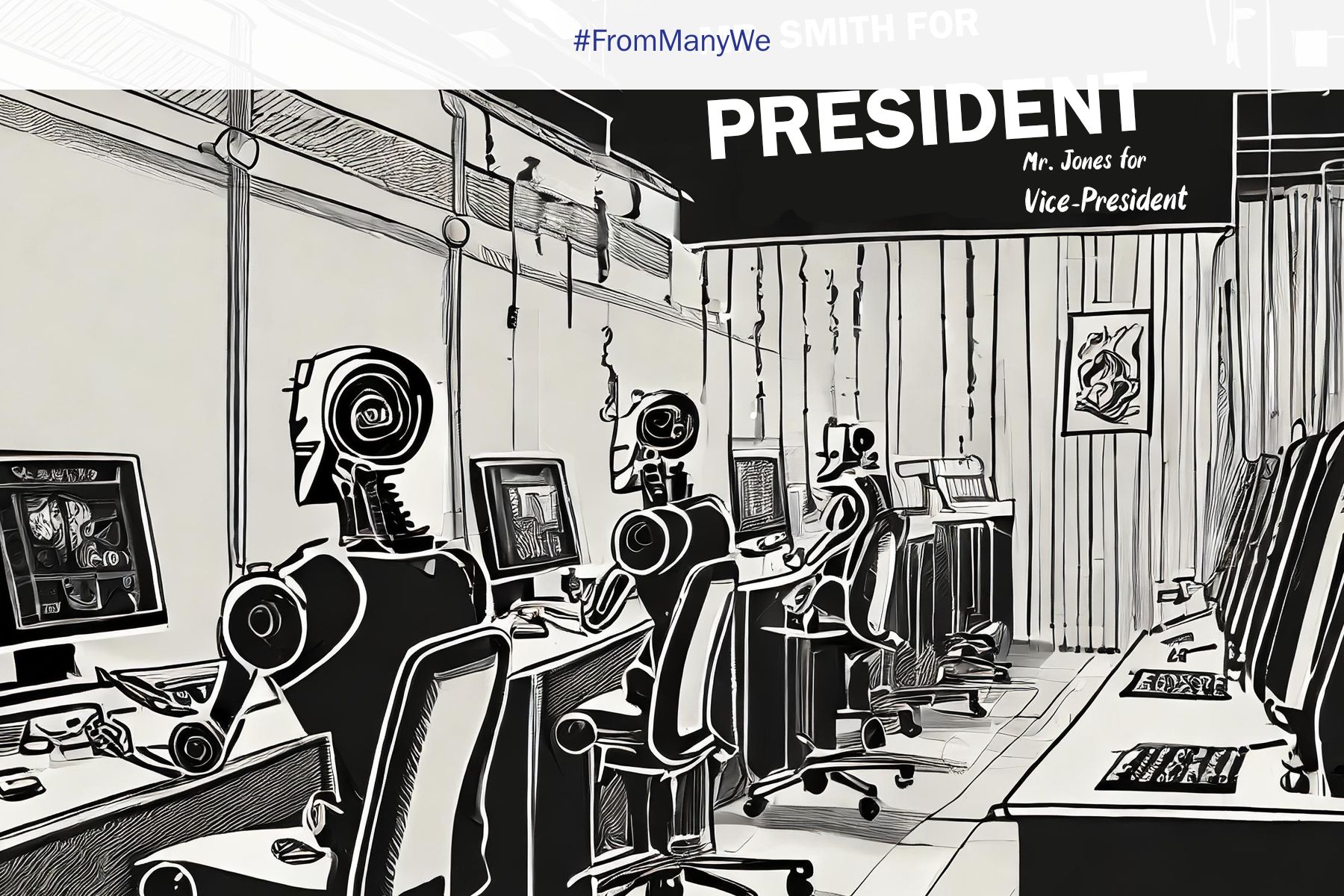

At the front of the classroom was Kai-Cheng Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern University and a world-leading expert on social bots. Social bots are social media accounts controlled wholly, or in part, by software. Some social bots are harmless: one offers a picture of a red fox every 60 minutes. Others are more dangerous: networks of bots (called botnets) can be used to promote worthless cybercurrencies or can create the appearance of grassroots support for a candidate or political issue.

Yang’s PhD work was conducted on the Botometer program, which was developed in Fil Menczer’s lab at the University of Indiana. Yang and colleagues refined the software so that it became highly accurate in detecting all sorts of malicious bots. Until recently, Botometer users could enter a handle for X, formerly Twitter, and quickly receive Botometer’s prediction on whether an account was run by a human or by a computer program.

Social Bots and the AI Threat

In mid-2023, Yang discovered a new breed of social bots driven by large language models, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT. These new powerful tools generate text that is difficult to distinguish from human-authored text. Yang’s detection tools had missed these bots because they looked very much like accounts run by humans. Their profile pictures had been generated with AI tools like This Person Does Not Exist and their content seemed utterly human. Yang was able to find these bots only from error messages like the one above, which was only triggered when the operators tried to get the bot to say something prohibited by the “guardrails” that OpenAI has put on their tools.

The botnet that Yang had found was used primarily to promote cryptocurrencies. But botnets can be used for political disinformation. In December 2022, a wave of spambots dominated Chinese-language X. Posts that documented protests against COVID lockdowns were overwhelmed with tweets about escort services and adult content. While the intent was to drown out rather than deceive, the more sophisticated botnet that Yang had found could easily be weaponized for political purposes.

How the Tech Platforms Are Obscuring the Threat

I was particularly chilled by Yang’s discovery because I have been tracking changes in the social media landscape that have made it more difficult to conduct research of all sorts, including studies using tools like Botometer. In March 2023, Elon Musk decided to end researcher access to the Application Programming Interface (API), a set of tools that allowed programmers to search X’s archives. To continue their work, Botometer’s researchers would need to pay the company $42,000 a month for access. Reddit, too, began charging steep fees for access to its API. My lab at UMass was forced to stop updating our tool, redditmap.social, which mapped conversations on Reddit.

Meta’s Instagram and Facebook have never been as open to researchers as X was before Musk’s takeover, but a valuable research tool called Crowdtangle allowed researchers to monitor trends across these networks. Unfortunately, Meta forced out Crowdtangle’s founder Brandon Silverman in 2021 and has starved the project of resources since, leading to a tool that’s far less useful for researchers than it once was.

Researchers Face New Legal and Political Risks

As social networks have become technically more difficult to study, they are also more legally risky to examine. In July 2023, Musk filed a lawsuit against the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), a nonprofit that researches online hate speech. The CCDH had reported that hateful speech targeting minoritized communities had increased under Musk’s management of the platform. The suit alleges that CCDH’s accusations have harmed X’s advertising business, but many legal analysts believe the suit exists mostly to deter criticism of Musk’s management of the platform.

Other mis- and disinformation researchers are experiencing harassment from an unusual direction: the US House of Representatives. House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan is investigating the theory that social media researchers have been working with the Biden administration to pressure social media platforms to censor right-leaning speech. While these accusations fundamentally mischaracterize how academic research operates, the investigations they’ve engendered have had a profound effect on researchers and have forced academic labs to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars responding to information requests.

In other words, social media has become significantly more difficult to study in the past year, just when we need to understand its influences more than ever. Combine the increasing unknowability of social media and the rise of generative AI with the wave of global elections in 2024, and we may be looking at a perfect storm. India and Taiwan are two countries with evidence of attempted election manipulation via social media in their past. What Yang’s talk told me was that even the very best researchers in the world are unprepared to fight against the systemic corruption of elections.

A Call for Transparency

One response to the anticipated rise of AI botnets is to focus on social media transparency. EU nations have passed legislation demanding increased auditability of large social media platforms as part of the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act. Even stronger transparency legislation has been proposed in the US with PATA, the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, which seeks to protect the right of researchers to study platforms both through APIs and through more controversial methods like “scraping” data from websites. But the right to research won’t be enough. We also need to protect researchers through groups like the Coalition for Independent Technology Research (CITR), an advocacy group started by academic, journalistic, and activist researchers to protect against attacks like those coming from Musk and Jim Jordan.

The future is always a surprise, but we do not need to be surprised by the 2024 elections. We just need to heed the warnings of researchers who study social media and politics.

Ethan Zuckerman teaches public policy, communication, and information at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and is the author of Mistrust: Why Losing Faith in Institutions Provides the Tools to Transform Them. He is also a founding board member of CITR.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.