No Kings, Just Citizens: Civil Society Asserts Its Democratic Power

The statement “No Kings” is meant to be an exclamation of democratic power by ordinary citizens. It is a call that should cause us to consider both the increase in executive power and the state of civil society in the third decade of the 21st century. Often, when faced with the fact that mass street mobilizations are not enough to gain decision-making power on their own, people point to the electoral system as a salve. However, organizers and activists have come to understand that there is a prior, neglected realm of political action that is essential for effective political action: civil society.

The Context of “No Kings”

“No Kings” is a call that came about amidst a long protest wave that started right at the turn of the century with the antiglobalization protests of 1999–2000. Since that time, we have been in what political scientists call a “cycle of contention,” with protest movements coming in waves quite close together. These waves have crested in quick succession in the form of mass protest actions on both the left and the right. In 2003, the anti-Iraq War protests then gave rise to the Immigrants’ Rights Movement in 2006, the emergence of the Tea Party in 2009, Occupy Wall Street in 2011, Black Lives Matter in 2013, #MeToo in 2017, March For Our Lives in 2019, both Black Lives Matter and Anti-Mask Mandate protests in 2020, and anti-Gaza War protests in 2024. In 2025, the current wave of protests is a response to the perceived extra-legal overreach of the second Trump administration and against the democratic backsliding of Congress and the Supreme Court as well as some governors, state legislatures, and attorney’s general. Consumer boycotts started in February and included street protests in March with continuing actions every month, including planned Good Trouble mobilizations on July 17.

Contrary to popular perception, participation in protests in 2025 has eclipsed participation in similar mobilizations during President Trump’s first term. Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman’s Crowd Counting Consortium at Harvard note that:

By the end of March 2025, there had been three times as many protests as had taken place in 2017. Protest has been surging since, with large boosts coming from major, multi-location actions in April and May . . . significantly, protest activity occurred throughout the country, including in rural and GOP-leaning towns.

While 2017 was characterized by single-day protests that had millions of participants in major cities, the 2025 mobilizations have been more numerous, more geographically dispersed, have included more kinds of action (notably economic noncooperation such as boycotts), and have included more participants overall. These protest actions have been organized by a variety of different groups from Black and Latino consumer groups to churches and the 50501 movement, People’s Union USA, and diverse smaller, local groups. However, national groups with established presences in politics, like Indivisible, have served crucial coordinating roles and are spreading the word about when demonstrations will take place and directing people to the contact information of smaller organizing groups. This form of distributed and networked organization has become typical in 21st century social movements. With each successive wave of street protests, boycotts, and other kinds of economic noncooperation, organizing groups can rely on a growing communication network to share the word about where and when to gather and other protest actions that interested participants can take.

This geographic dispersion may be an intentional tactic. A common refrain of participants who recounted their attendance at protests on social media has been that they deliberately mobilized in their localities, including small towns and counties, rather than going to larger nearby cities. Building a sense of local solidarity shows that those who oppose the administration’s policies are not isolated on the coasts or in the largest metros but are instead a part of a vibrant, widespread, and diverse group who can be found outside the confines of the calcified stereotypes of “red and blue” America. One participant in Pittsboro, North Carolina, commented, “We could have gone to larger rallies in bigger cities (Raleigh, Durham, and Greensboro are all about an hour away) but instead, we peacefully took over our town.”

Protests have been overwhelmingly peaceful. The Crowd Counting Consortium has found that out of 4,770 anti-Trump protests in April and May, there were police injuries at only three events and participant injuries or property damage at only two events. That means that 99.5% of the time, there has been no violence of any kind at protests. In fact, the wave of protests since Trump’s inauguration has been characterized by a family-friendly atmosphere, perhaps owing to the demographic skew of attendees toward both seniors and parents with young children.

This deliberate attempt to build community connections locally is a critically important and distinct aspect of the current wave of protests. It is connected to some realities about changes in the social media environment and the need to rebuild local community connection, education, and support offline as a basis for political action.

Changes to the Social Media Environment

One of the characteristics of 21st century social movements has been the use of social media to spread awareness about political concerns, communicate ideas, and publicize protest actions. However, the social media environment has changed over time, and organizers and activists have learned some valuable lessons during this century’s long cycle of contention.

The most significant changes in the social media environment stem from both consolidation of ownership and changes in owner philosophies. Meta, the parent company of Facebook, systematically bought up competing social networks throughout the last 15 years, bringing the popular platforms Instagram and WhatsApp under their banner and launching the Twitter competitor Threads in 2023. Meta uses algorithms that deemphasize news content and external links and has changed its approach to content moderation, decreasing efforts to vet posts for accuracy. Additionally, billionaire political activist Elon Musk bought the comparatively small, but incredibly influential, social network Twitter (now known as X) in 2022. Musk declared his desire to buy Twitter expressly because he wished to change the content moderation rules so that what he calls “free speech” (but what experts have deemed right-wing extremism) would be more welcome on the platform, and “woke” points of view could be curbed and contained. These alterations in the algorithms and content moderation features of the largest and most influential social media platforms have made them less effective tools for activists who seek to reach broad audiences.

These changes have also coincided with a growing realization that although social media has been extremely useful as a communication tool for drawing people into the streets and helping to produce the largest mass mobilizations in US history in the 2020s, it has also produced a unique discontinuity. Social media has allowed for mobilization (assembling people for a one-time or episodic event) but has not necessarily led to democratic organizing (bringing people into a community of action that serves as a space where they can build interpersonal connections, problem-solving capacity, and collective agency over time). Democratic organizing takes place in timespans longer than election cycles and creates what political scientist Katrina Gamble calls “civic homes.” These are places that cultivate a sense of belonging and foster environments where people can make durable interpersonal connections and build mutual support while also acquiring civic skills like collaboration, leadership development, and collective agency.

The Democratic Necessity of Civil Society

A dense and flourishing civil society is essential for building political power. Such forms of organizing go beyond the expressive power of mass mobilization and furnish contexts in which people can develop resources for persistent and resilient political action that can enforce demands for accountability from decision makers.

A lesson that political scientists know, but have not taken as seriously as we should, is that democracies require robust civil society. Civil society is the realm of organized social life that is voluntarily generated by participants who choose to associate together based on shared values, goals, and interests independent from governing duties or commercial interests. Civil society includes organizations that range from parent teacher associations and unions to garden clubs and community sports leagues.

Unfortunately, civil society has been in decline. Sociologist Robert Putnam pointed out the “strange disappearance of civic America” beginning in the 1990s, a deterioration that has only accelerated in the 21st century.

This is a major problem. The decline of civil society correlates with the increasing social isolation of Americans and has corresponded with a cratering of trust in both institutions and among one another. This is not coincidental. People need social relationships. They are essential to our well-being, but that does not mean that we are born with social skills or into contexts that allow for relationality, collective problem-solving, other-regarding behaviors, conflict mediation, or any of the myriad skills that are necessary for people to live and govern together—to behave as democratic citizens in democratic society. Indeed, increasing economic inequality, social marginalization, and the erosion of communal or “third spaces” that once facilitated organic connections all contribute to the democracy-eroding ills of social mistrust, decreased participation, and calcified polarization.

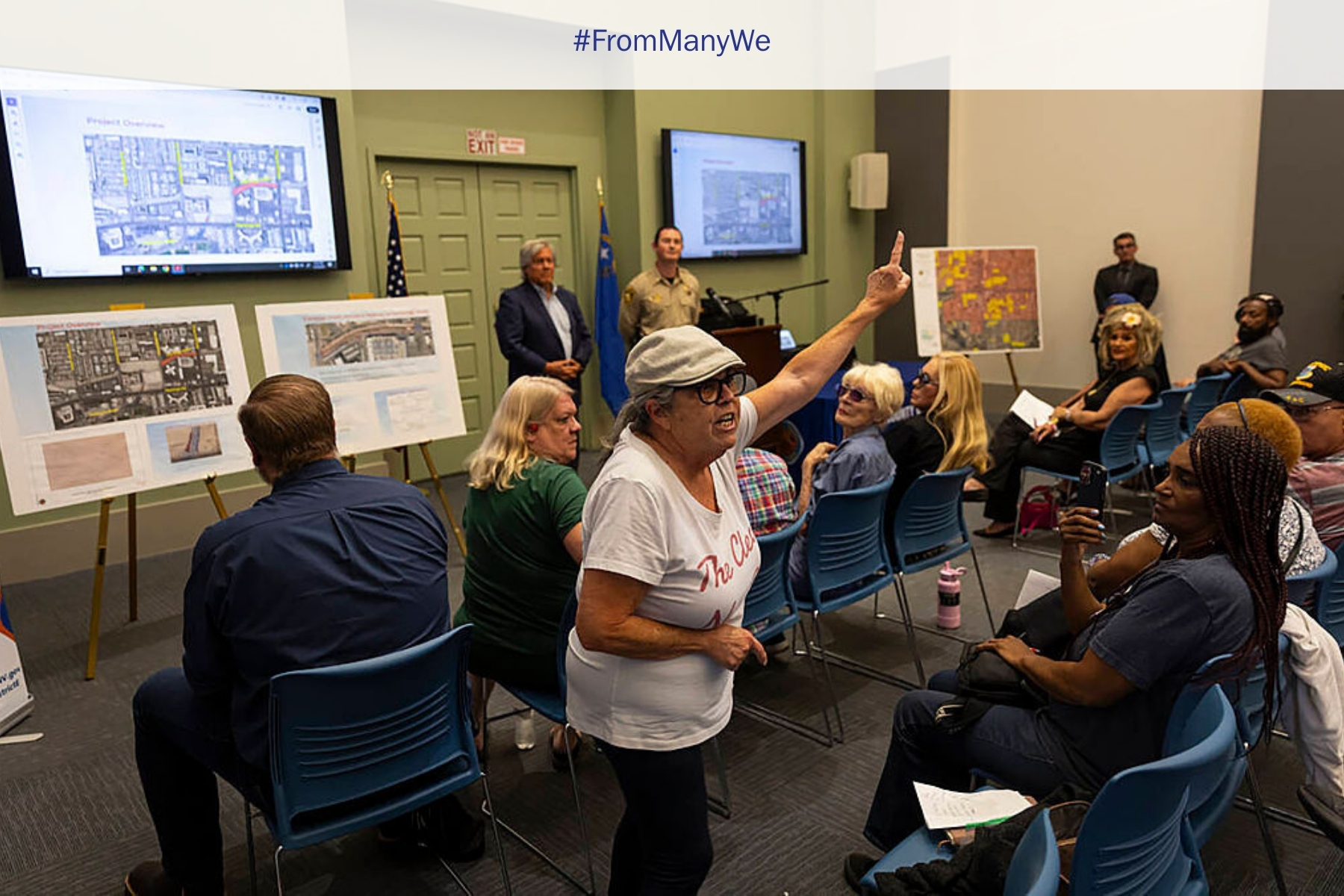

Social movement groups can act as civil society organizations, but 21st century movements are only just starting to invest significant amounts of time and resources in building long-term civic homes for participants. This is because this century brought with it an unprecedented mismatch in communication power and civic strength. Large protests during the 20th century were smaller in both size and geographic proliferation than protest movements of today. However, protest movements of the past were more firmly rooted in local civic structures like churches, social clubs, secret societies, sports leagues, hobby and charity organizations, neighborhood associations, and other place-based formations that offer people spaces to gather with one another; learn from one another; form opinions, analysis and action plans; and offer support. The form of protest that we see with “No Kings,” which are proliferate, locally rooted, and geographically diverse, may provide for less spectacle than large mobilizations based primarily in big cities, but it reflects a new organizational practice that is essential for building power. Rebuilding deep civic roots is necessary for the ongoing mobilizations of 2025 and beyond to meet serious democratic challenges and to make the declaration that the US has never had and shall never have a king. This declaration remains true as the nation enters its 250th year.

Deva Woodly is professor of political science at Brown University and a Charles F. Kettering Foundation research fellow.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.