Ordering Power: JD Vance’s Moral Logic and America’s Authoritarian Turn

In an interview on FOX News in February, Vice President JD Vance, a converted Catholic, invoked what he called an “old-school Christian concept” to validate the Trump administration’s policies toward foreigners and immigrants: “You love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country. And then after that, you can . . . prioritize the rest of the world.” The late Pope Francis responded that Christianity teaches “a fraternity open to all, without exception.” The debate resurfaced when Cardinal Robert Prevost was found to have affirmed Francis’s inclusive vision on social media prior to his selection as Pope Leo XIV. Far beyond immigration policy, this difference in worldview reveals the core values at the heart of the administration’s agenda, and the extent of its threats to democracy.

Ordo Amoris: Concentric or Complex?

Following his initial comment, Vance confirmed he was referring to ordo amoris, “order of love,” a concept originating in the works of the early Christian theologians St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. The concept may seem obscure, but it is surely familiar among the far-right and conservative Catholic intellectuals with whom Vance is known to associate. However, upon closer examination, Vance’s comments suggest a divergent logic that is not inherent in the original teaching but has become a Christian veneer for an exclusionary mindset.

Augustine developed his concept of love while writing in the later stages of the Roman Empire, a time when the Roman value system remained strong despite signs of instability. In this context, Christianity’s emphasis on love and humility represented an alternative to the Roman valuation of wealth and power. In this context, according to Augustine, “All men are to be loved equally. But since you cannot do good to all, you are to pay special regard to those who, by the accidents of time, or place, or circumstance, are brought into closer connection with you.” While Augustine suggests love can and should be universal, convenience and circumstance will naturally favor doing good mostly for those whom are closest. Augustine never stated people should be indifferent toward suffering. Rather, failure to offer assistance may be acceptable only when the practical capacity to benefit others is limited.

Vance’s reinterpretation of ordo amoris goes much further than his predecessors. In Vance’s way of thinking, love is neither universal nor equal. Vance follows a rigid logic in which the amount of love we experience, and our obligations toward others, are defined primarily by geography. Love is ordered in a specific priority, starting with one’s family and progressing out into the larger world. According to Vance, we should prioritize our own communities over foreign others, not only out of practical convenience but also because love itself can and should be experienced only among those who are in closest community with each other. Moreover, Vance equates sympathy for foreigners with hatred of America, as if affection for one is mutually exclusive with affection for the other. Using this logic, he deduces that liberals, “seem to hate citizens of their own country.”

Francis presents a different view. In an apparent direct rebuke to Vance, Francis writes, “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups. The human person is a subject with dignity who, through the constitutive relationship with all, especially with the poorest, can gradually mature in his identity and vocation.” Francis suggests a more complex or flexible ordering. Rather than concentric circles radiating outward from the individual, love could instead be imagined as a web of overlapping shapes, or an infinitely complex network map, in which Christians push beyond their particular communities, to engage with and improve the larger world.

The Dangers of Concentric Thinking

Vance’s worldview has dangerous implications for a large, diverse, and pluralistic society. Vance’s logic divides the world into tightly knit, inner-circle groups and remote outsiders. This thinking echoes the distinction American political scientist Robert Putnam makes between communities formed by bonding within groups versus bridging across groups. Bonding can be achieved by like-minded members naturally associating with one another but also by excluding outsiders or purging of difference from within.

Beyond foreigners and immigrants, cultural difference can act in much the same way as geographical distance, leading those outside the majority to be viewed with indifference or fear. Vance’s concentric logic suggests a particular and narrow understanding of what America is and who counts as American. For Vance, that group should be as circumscribed as possible so as to achieve cohesion within the group.

Viewing outsiders with indifference is the first step toward seeing them as less than human, or as enemies. Vance claims that his concentric thinking does not mean hatred toward others, but his own actions suggest otherwise. During the 2024 campaign, Vance knowingly spread false rumors that went viral about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, with the rationale that the interests of naturalized Americans justified the propagation of false and harmful stereotypes: “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do.”

While Vance’s concentric thinking reinforces a harshness toward outsiders, it also suggests hyper-forgiveness toward the nation. Vance’s remark about liberal opponents hating America echoes the administration’s critique of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) and related programs that draw attention to America’s history of racial discrimination, as if acknowledging historical injustices is incompatible with affirming democratic principles. The administration’s policies, seen in the context of Vance’s framework, seem to reflect a “my country, right or wrong” attitude in which loyalty to the state does not allow for critical thought.

Concentric Thinking and Political Power

While Vance’s nationalism prioritizes the country above the rest of the world, his framework also places more proximate groups above the country. The natural tendency to seek to help one’s own might be fine as a personal code, but it is troubling when extended into politics. Weaponizing the state on behalf of a more proximate group would seem to be acceptable, or even desirable, within his concentric worldview. For example, if helping one’s friends is of highest moral importance, why not use political power to benefit one’s religious group? Indeed, the administration’s Project 2025 policy agenda is deeply informed by Christian nationalism, particularly reflected in its attacks on trans rights. Of course, Vance’s appeal to ordo amoris itself signals his intent to wield political power to encourage religiosity and “Christian” behavior.

Taken to its furthest extreme, Vance’s concentric thinking leads ultimately to no other principle than that of self-love. If family and friends are prior to neighbor and citizen, any form of corruption can easily be justified. Following 3,740 documented cases of conflict of interest in the first Trump administration, recent news that President Trump appears ready to accept a $400 million luxury plane from Qatar is a sign that the administration is again open for business. For a supposedly Christian ethical code, Vance’s worldview, and his administration’s behavior, are strikingly amoral.

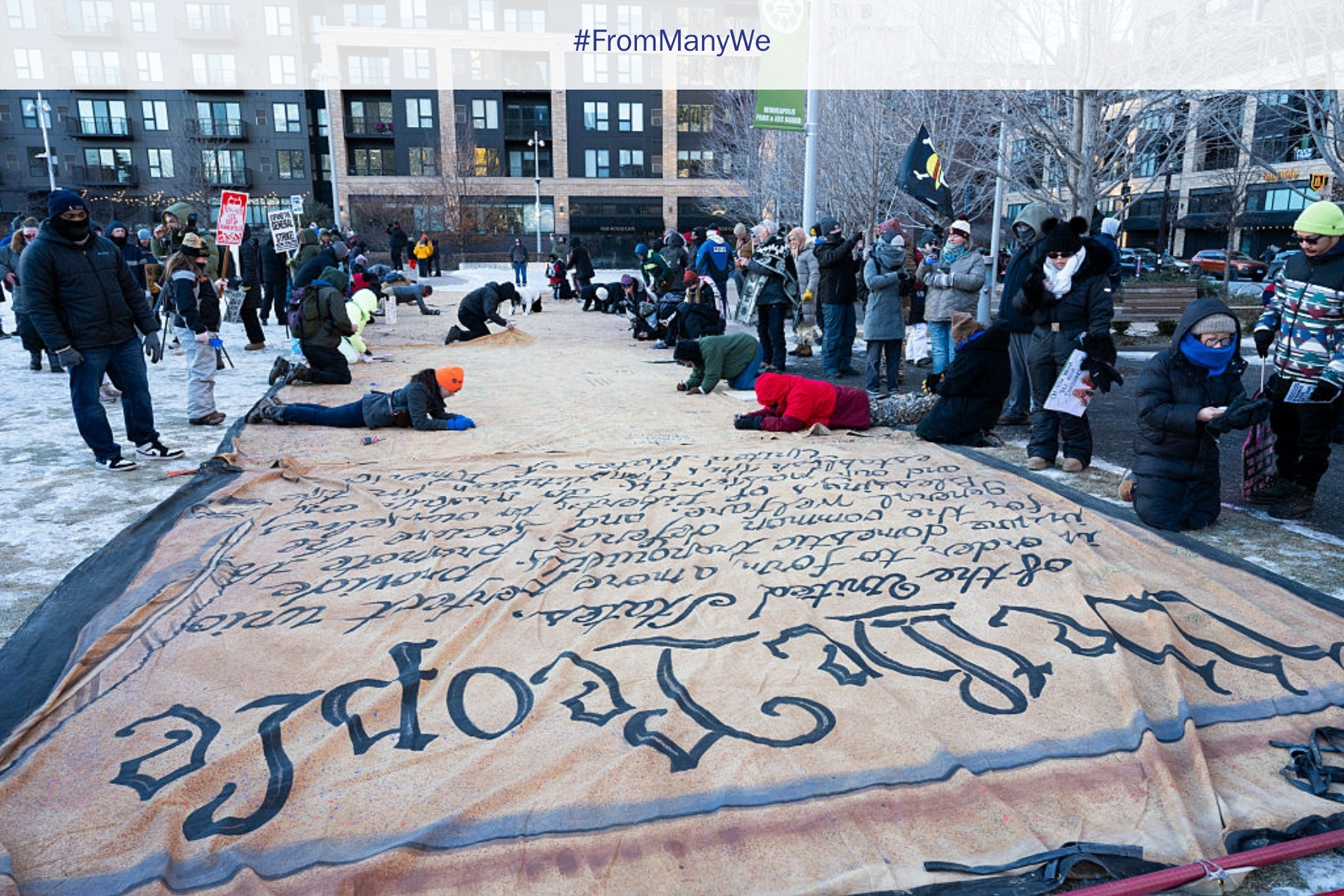

The exchange over ordo amoris highlights the need for a strong, shared national identity beyond a naive and abstract cosmopolitanism. However, contrary to Vance, such a national identity need not be achieved through bonding and exclusion. Rather, the exchange also highlights a way forward, through the affirmation of our shared humanity and diversity.

Derek W. M. Barker is a program officer at the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, a political theorist, and the lead editor of the foundation’s blog series From Many, We.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.