Our National Mosaic: Weaving a Multiracial Democracy

The fight over immigration is not just a policy debate; it is a battle over belonging, and power. White nationalists know this. Unlike white supremacy, which is an ideology of racial superiority, I'm referring to a broader ideology of dominance that can show up through religion, policy, race, economics, and gender roles. White nationalists are not trying to preserve a real past but instead are trying to enforce a traditional ideal of America where Whiteness equals unfettered dominance. But the truth is, the roots of this land have always been multiracial, multilingual, and spiritually diverse. Long before borders and the US Constitution, this continent was shaped by Indigenous nations, African communities, and working people of all colors. What White nationalism fears is not a new future but an old truth that has been yearning to reclaim its place. To build upon our democracy, it is necessary to acknowledge and celebrate this truth as a blessing rather than a threat.

A Life in Diversity and Community

I grew up in Newark, New Jersey, raised in the wake of the civil rights movement and the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention, where civic imagination and multiracial solidarity collided to create a fierce and innovative environment. The city's history, like my own, sits at the intersection of migration, displacement, and reimagination. My family carries stories from the American South, Central America, and the Caribbean, from exile and return, from faith and resistance. We carried stories across generations, lit candles on street corners, organized in church basements, and refuted invisibility wherever it attacked us. Despite popular stereotypes about Newark and people of color, I experienced a tight-knit community that included professionals, the unemployed, a homeless shelter adjacent to the city's most expensive homes, and young and old residents of all races and ethnicities. They all held a shared responsibility for one another and were active participants in designing our future. And while I no longer sit in the pews of my family's church each Sunday, my life is steeped in the sacred. My faith, like my understanding of democracy, lives in those early lessons of community; it is how I show up for others. It is from this ground that I approach our current immigration struggle, not just as an issue, but as a mirror to who we have been, who we are, and who we could become as a nation.

Immigration and Identity

This country has never had a neutral relationship with immigration. The right to settle here versus the concept of being Indigenous has long defined citizenship for many. And so, citizenship has always been racialized and politicized and used as a cudgel or a compass.

Immigration is not just about policy and political tactics. It is about identity and our imagination for the future. In this moment of rising authoritarianism, it calls us to rethink not just who belongs in the United States, but how we have been taught to see ourselves, and how we might redefine citizenship beyond our colonial settler reality. This reality refers to a nation founded not simply on democratic systems, which originate with Indigenous nations, but on the displacement of Indigenous peoples and the forced labor of enslaved Africans. Land, labor, and laws were designed to serve a settler class and their descendants. Our immigration policy can serve as a mirror. When reimagined, immigration policy and thought can help to understand belonging, which is the bedrock upon which the policies of a healthier democracy can be built.

The False Allure of Whiteness

White nationalism isn't only about race, it's about a vision of belonging that is defined by dominance. Even people of color have found allegiance to White nationalism in this sense connecting to the idea of Whiteness: wealth, the law, heteronormativity, able-bodiedness, and Western Christianity. Justice, compassion, and universal dignity can transcend specific doctrines. Belonging is rooted in presence, in neighborliness, and in shared purpose.

We must reject the idea that the construct of Whiteness is aspirational. Proximity to power is not the same as safety. And immigration is one of the most powerful lenses through which we can examine and reclaim our democracy.

Latine identity offers a bold alternative. Unlike the identifier "Hispanic," which centers a relationship to Spanish colonial ancestry, "Latino/Latine" identity bridges racial, ethnic, national, class, gender, and spiritual differences. It is not a monolith; at its highest ideal, it is a mosaic. Afro-Latines, Indigenous communities, queer and trans folk, working-class migrants, Pentecostal elders, undocumented students: all of them belong in this storybook. And yet, the multitudes of stories are often erased from both policy conversations and immigration movement leadership, largely because their textured narrative does not easily translate to the masses who are used to digesting White nationalism as the status quo.

This helps explain why Christian nationalism and, in some cases, its explicitly racialized variants, have gained traction in parts of the Latine community. The appeal is not always ideological at first. Often, it's about presence: someone shows up, offers prayer, food, and a sense of belonging. As highlighted in a recent NPR episode, many Latine evangelicals turned toward the Right not because of policy alignment but because their spiritual, emotional, and material needs were acknowledged. The message came second; the relationship came first. Christian nationalism, with roots in White nationalism, is increasingly transcending racial boundaries. It is drawing in non-White communities through shared religious language and cultural values even while those same movements actively work to dismantle the rights of many within those communities themselves. There's also something deeper at play: the desire to align with power. In a nation where Whiteness is still often equated with safety, order, and legitimacy, Christian nationalism can offer a sense of clarity and protection, especially to those who feel overlooked and are claiming their station in society.

Race, Citizenship, and Religion Are All Connected

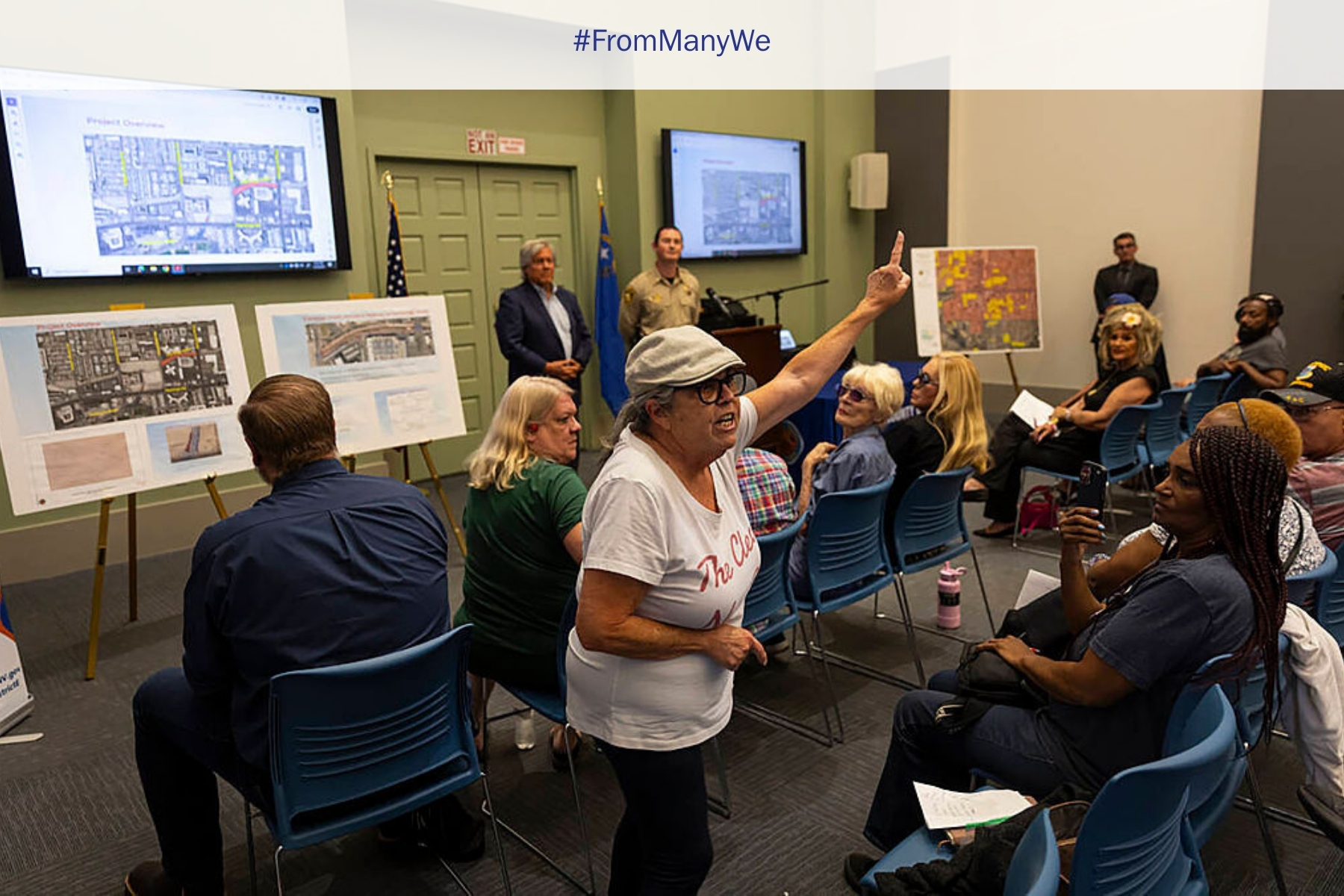

The work of stitching together a just, pluralistic democracy is not about left versus right. It is about memory versus amnesia. Consciousness versus convenience. Those of us interested in a more democratic future must organize with the same depth and commitment as White nationalists, all while remembering the critical role that empathy and tenderness must play. Not to convert people to our politics, but to reconnect folks to their power. We must hold firm that acknowledging complexity and historical injustice is not "being divisive," but rather is necessary for genuine, lasting unity. We must simultaneously ensure that we address the day-to-day issues impacting our community. These efforts will require all of us across the political spectrum to do both internal and institutional work.

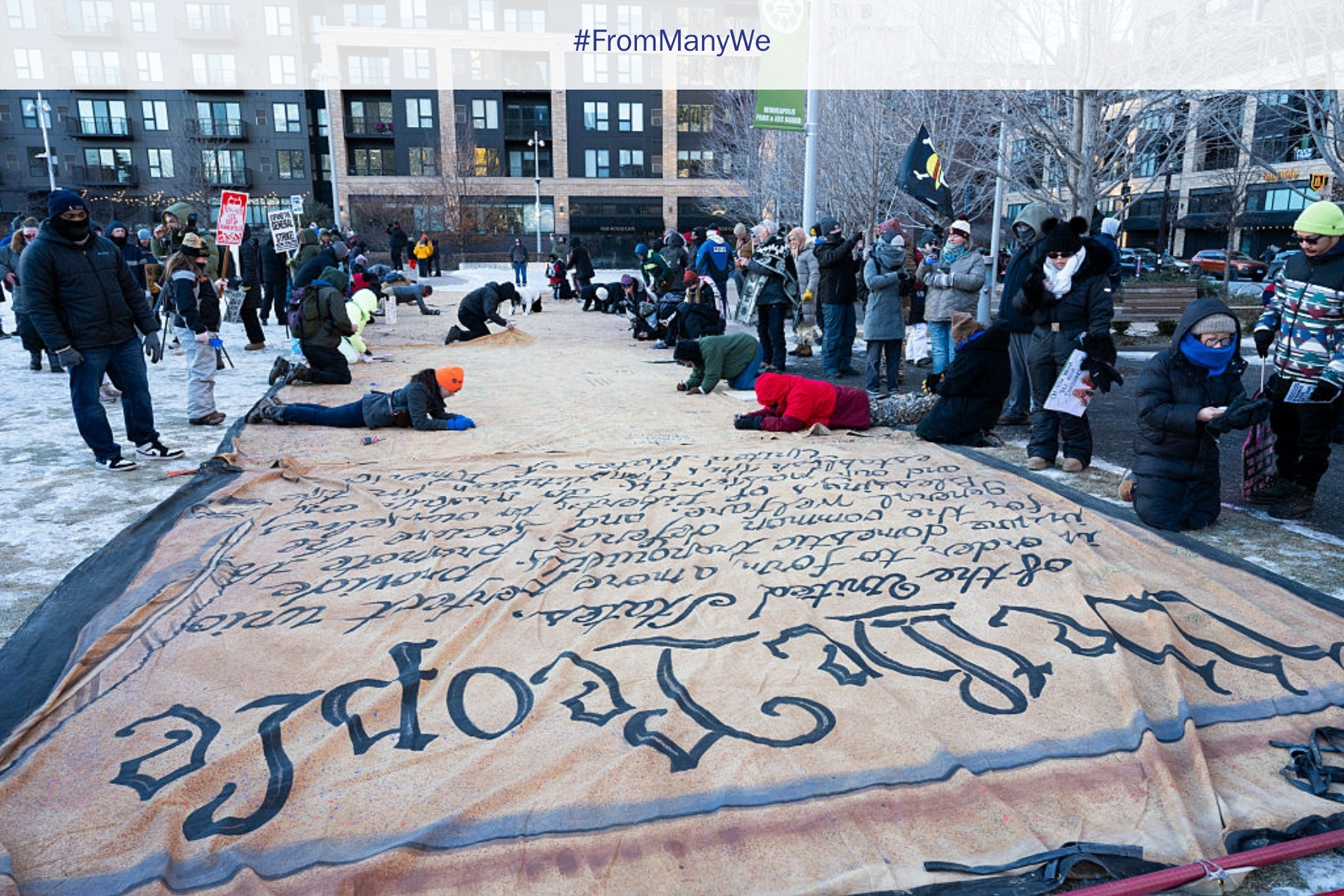

The civil rights movement did not just secure voting rights, it also reshaped the idea of who gets to be American. That movement cracked open immigration policy in 1965 and dismantled a racist quota system by making space for citizens of the world to enter into the United States on more equal terms. Democracy did not expand on its own; it was demanded and redefined by those who refused exclusion as destiny.

To defeat White nationalism, not just as a political threat, but as an enduring ideology, we must reclaim the stories that sustain liberation: stories of crossing and of return, of sanctuary and survival, of identities not erased for assimilation but honored as the building blocks of a shared future.

A Strategy to Defeat White Nationalism

At the heart of White nationalist strategy is division—using race, gender, sexuality, and reproductive justice as wedges to fracture the very coalitions that could transform democracy. We have seen this tactic unfold in Latine communities, including Afro-Latine and queer spaces, where faith is often weaponized to shame or exclude rather than liberate. But our bodies and our faith traditions carry more profound truths, ones that make space for complexity, contradiction, and collective care. True democracy will not be built by choosing which parts of us are acceptable enough to bring into public life. It will be built when we refuse to trade belonging for conformity and when Indigenous, Afro-Latines, queer and trans folks, immigrants, refugees and migrants from various nations, and parents across the political spectrum do not stand behind one issue or identity but for each other.

Again, for those of us who believe in the promise of democracy, this is not about fixing a broken system or forcing a single message. It is about remembering that we were never meant to fit into a machine. It is about organizing a future where our children know that borders—geographic, ideological, and so on—do not define belonging, and that faith is not a wall but a wide and open pasture.

If you are reading this, whether you are clergy or culture worker, policy advocate or parent, begin here: What does democracy require of you, in your body, in your community? And remember, democracy is not an individualist project; it demands courage from institutions. From our pulpits and publications to our philanthropic strategies, we must invest in narratives and leadership that complicate the dominant frame rather than echoing it. When we face these questions fully, we might find ourselves a more democratic nation again.

Bryan Epps is a movement builder, strategist, and storyteller leading Sojourners’ faith-based justice programs. Shaped by his Newark, NJ, roots, he is committed to abolition and contributes this piece with two decades of experience advancing change.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.