Practical Advice for Reclaiming Democracy

Want to know what you can do to fight authoritarianism? Organizer Daniel Hunter joins host Alex Lovit to give practical advice for people seeking to reclaim democracy in the United States. Daniel Hunter has studied authoritarianism and resistance around the world. He is an educator with Freedom Trainers and the director of Choose Democracy.

Share Episode

Practical Advice for Reclaiming Democracy

Want to know what you can do to fight authoritarianism? Organizer Daniel Hunter joins host Alex Lovit to give practical advice for people seeking to reclaim democracy in the United States. Daniel Hunter has studied authoritarianism and resistance around the world. He is an educator with Freedom Trainers and the director of Choose Democracy.

Share Episode

Practical Advice for Reclaiming Democracy

Listen & Subscribe

Want to know what you can do to fight authoritarianism? Organizer Daniel Hunter joins host Alex Lovit to give practical advice for people seeking to reclaim democracy in the United States. Daniel Hunter has studied authoritarianism and resistance around the world. He is an educator with Freedom Trainers and the director of Choose Democracy.

Alex Lovit: If you’re listening to this, you are probably worried about democracy. I know I am. The United States has always been a flawed democracy. We’ve always had too much inequality and prejudice in our country, and we should work on solving those problems. But these days, I worry about whether American democracy will endure it all, whether or not we’ll continue to have free and fair elections and representative government. It’s a scary moment. And what’s worst is I don’t know what to do about it. It’s not an election year. We can protest and call our representatives and post on social media about all the things we’re upset about, and we should do those things, but they can feel futile and they probably are insufficient. So what could we do right now that would work? My guest today has answers.

You are listening to The Context. It’s a show from the Charles F. Kettering Foundation about how to get democracy to work for everyone and why that’s so hard to do. I’m your host, Alex Lovit. Today I am speaking with Daniel Hunter. Daniel has studied resistance to authoritarianism around the globe, and he’s used those ground-up lessons to teach thousands of people how to resist effectively. He’s a trainer with the organizations Freedom Trainers and Choose Democracy, which he also co-founded and directs, and he’s here today to tell us what we can do to successfully counter authoritarianism in the U.S.

One quick note before we dive in. In this interview, Daniel uses the phrase concentration camps to describe immigrant detention facilities. That term may be jarring, but it accurately describes the harsh conditions and lack of due process detainees experience. We recognize the historical weight that this language carries.

Daniel Hunter, welcome to The Context.

Daniel Hunter: Thank you so much for having me.

Alex Lovit: I want to talk to you about two Ps, psychology and power, because I think you have important insights into both. Let’s start with psychology. You’ve studied authoritarianism and resistance all over the world. How does authoritarianism work psychologically? How do authoritarians want us to feel?

Daniel Hunter: Well, the first thing is they want you to feel scared. So some of the moves that we’ve seen from Donald Trump have been classic examples of that. So deploying the military, even without a real operation plan, what they’re doing isn’t clear in terms of the behavior. The impact that they’re trying to drive is one of fear in the population. Othering, that’s part of the driving of fear is trying to create storylines in which they divide the population, “These are good people, these are bad people,” and the bad people should be eliminated, marginalized, arrested, jailed, et cetera. And, “If you’re not in my good graces, you might become one of the bad people.” So it fears a driving attitude of authoritarian, but it’s not necessarily the thing that causes an authoritarian to arise. It’s not as though the population is inherently scared, and that’s just why they choose. As we’ve seen, more and more people are voting in authoritarians around the globe, but it emerges out of people’s sense of isolation from each other out of people’s sense of chaos in the environment.

I think we’re all living in a world in which there is more and more instability and people are sensing it in this period of time. And so, with rising instability around the climate crisis, around the wealth inequality, around name your crisis that you’re experiencing, do you have enough support around you to feel like you can weather it? And as the social fabric frays, people feel more and more isolated. So Hannah Arendt wrote in her book, Origins of Totalitarianism, social isolation is the primary driver of the idea that people are locked in their heads with these ideas, trying to process the world in a scary time or unsettling time and aren’t able to do it with other people. And therefore, they lock into some ideology that can just give them simple answers for what’s going on, “We need a strong man, we need someone who can just tell us what to do, tell us who the good people are and tell us who the bad people are and we can eliminate it.” And that becomes a driver for people picking an authoritarian because they’re disconnected, out of touch with each other.

Alex Lovit: So if I want to oppose authoritarianism, you’re saying fear is a major tactic that they’re using, but it is scary. I have reason to be scared. Are there ways that I should prepare myself psychologically to go into a fight against authoritarianism?

Daniel Hunter: Psychologically, there’s a lot of things you could do. I’ll start though with the most practical thing, which is, have some other people that you talk these things through with on the regular to be in some kind of motion. So do some kind of action, whether that’s protesting in the streets or whether that’s simply being in solidarity with each other as you make phone calls or write letters. But the idea here is that you’ve got to be in some kind of formation connection with some other people. That’s the primary thing, because the psychology is difficult to achieve if you’re alone. What is it that we’re looking for psychologically? For the times ahead, it’s a number of things. One of them is having a realistic assessment as best you can, having a realistic assessment of what may come and the different directions that things can unfold. And that doesn’t mean it’s going to go like this with certainty.

History right now is very open about its directions. Yes, Trump could have total state control, and MAGA could be entrenched in power for the next 30 years. That is one way history could tilt. It’s also, Trump and MAGA movement is removed, and the country awakens out of its slumber and decides to act in decisive ways to follow through on values that people hold on equality and uplifting human values across the board. And that’s another way that this thing could tilt. This moment requires us to be prepared for some different options. So a realistic assessment means a flexible assessment that many things are true at the same time, and so, it’s not one way or the other. It’s not all good, all bad. It’s in conflict, in tension. And so, depending on where you put your attention, you could see more of one or more the other.

So something that one of our preeminent analysts at the time, Rebecca Solnit, has been reminding people is it’s not healthy to just focus on all the things that Trump is able to do successfully. You also have to focus on the things that the people are doing to push back. Otherwise, you have a bad analysis, a bad take. So that’s good psychology. It’s also good power analysis, but it’s good psychology because it helps us free ourselves from just the notion of it’s all or nothing. That requires more instability, that requires more grounding for us to be able to hold an analysis that is in flux, in tension, in conflict constantly. Human beings don’t like that. We like simple stories, simple answers. So uncertainty would be an element of what I’ve noticed people who do the best anti-authoritarian organizing, they’re able to hold complexity, hold a lot of uncertainty within themselves.

Alex Lovit: Which is a psychological challenge.

Daniel Hunter: Which is a psychological challenge. And just having some good friends around, having some good people who love you and care for you so that you’re holding some balance, that some contradictory things can be true. You can be living a nice life in an authoritarian regime. You can be having a good day even while bad things are happening. You can be incredibly sad and honoring that even while others around you’re cheering something else political that’s a win, that those are contradictions that are sometimes difficult for some of us to hold. And so, some of those things are important.

Alex Lovit: So that’s a little bit about psychology, and I really respect that your work tells us to pay attention to that, that we need to wrestle with our own emotions and that if we leave that to the side, we won’t be as effective in trying to challenge authoritarianism. I do also want to ask you about power. One thing that you’ve pointed out about power is that pretty much all forms of power are about influence on other people. So in a sense, all power is psychological then. Talk a little bit about that. We think of the government as powerful, but what does that power mean?

Daniel Hunter: I’ve been thinking about this, how to describe this situation that we’re in because we’re in this weird moment in which, over and over again, we’re told by any number of media sources, “Trump does this.” “Trump takes control of MPD.” “Trump builds a new concentration camp.” “Trump…” And Trump doesn’t do anything. I think we just have to get a clear labor analysis on where we are. Trump doesn’t do things. He doesn’t lift hammers, he doesn’t build buildings, he doesn’t enforce ICE policy, he doesn’t do things. He’s a manager. He’s telling other people to do things. We need to get a clear analysis in these times of who does what things, because three things are happening. One, many of the things that headlines tell us are happening that Trump has announced he’s doing, he does not actually have the power and cannot do. So reinforcing the storyline that he can do it is unhelpful.

Two, even in cases when he could legally do it, he doesn’t do it. Someone else implements those things. Someone else lifts hammers and builds concentration camps. The reason that’s so important for us to understand is, every layer of authoritarian regime is compliant in making it happen. Even if people don’t personally like the regime, but if they still build a concentration camp, they still implement said policy, they are then part of that regime. And compliance at every layer is how regimes are able to be successful. It’s not because Trump does all these things, it’s because he’s getting other people to comply. And that means, three, we have a very clear direct path for people who are interested in trying to unseat an unjust regime like this, which is the path of noncompliance. That is a fairly clear pathway. And so, what we found, there’s academic research to back this up, what we’ve found over watching different authoritarian struggles around the globe is those that simply try an armed struggle, or those that simply try to use the electoral process, they are unsuccessful.

So the democratic playbook that is being tried out right now where Hakeem Jeffries tries to say, “Trump, we don’t like what you’re doing. It’s not constitutional.” Those don’t work. You actually have to be in a better power analysis than we’re just going to contest power with political power. Instead, it’s about organizing society to not comply with illegal, unjust and wrongful orders. What that means, and what that looks like is, the whittling away of different institutions, pillars, who their labor does these things. And so, that’s a different way than I think a lot of organizers, activists, movement players, et cetera have worked in these times.

And so, this is the insight that emerges out of what are the successful anti-authoritarian or anti-dictatorship struggles they have understood and analyzed through this, we sometimes talk about as the pillars of support, they’ve analyze the idea that there are institutions, pillars that are required, their behavior… Again, it doesn’t matter what they think or believe, it matters what you do. So they are holding up the regime, and therefore, they can make choices to stop holding it up. That’s bold. That requires risks. That’s a challenge, but that’s power.

Alex Lovit: So give me an example. What are some of these pillars of support?

Daniel Hunter: I’ll give one example out of Serbia, such a clear example and then unusually vivid. So under Slobodan Milosevic, there’s a group Otpor who they taught this pillars of support, actually. This is a training they required everybody who’s a member of their organization, the anti-Milosevic organization, they required everybody to go through training and they learned the pillars of support. One of the things that they analyzed was the military are critical for Milosevic’s power, the military and the police. And so, rather than simply being oppositional to the military, which they were oppositional to the military’s position and the police, how they’re being used, but they also understood that these are neighbors, and therefore, they can also be moved. So they were aiming for defections. Now, defections do not typically happen quickly. They take time, but they can be set up over a period of time. So one of the things that they would do, they did lots of protests and so forth and regularly got beaten up by the police, tortured and so on.

And so, their response, however, is very telling. So with some of the police officers who had beat them up the most aggressively, they would go to their houses and they would hold up posters, pictures even of say one of the kid’s bloodiest body that was beaten up and they would say a version of shame and “You can do better,” and so forth. But they would say a real message which is, “You will have a chance to join us. Even you will have a chance to join our side. It is never too early to join.” And again, they’re not just hurting them, they’re also targeting the neighbors who are watching this. And the intention is to get a neighborhood conversation where a neighbor turns to someone and says, “Why are you beating up these 14-year-olds?” And to begin to soften?

Not everything they did was just push like that. They also pulled, so they would hold days of remembrance for people who were killed in line of duty. And so, as protesters, they held a day of remembrance and read the names of all the police officers who were killed in the line of duty, as well as all the folks who were also killed by police from their ranks, and describing them all as victims of the Milosevic regime, that, “This, a level of violence that we’re experiencing is not necessary and we have a person who’s responsible.” I’m jumping a whole bunch of different activities, but you get the sense of what they’re up to. Fast-forward to a moment in time in which, Milosevic, under enough pressure, called an election, they got it verified that in fact their candidate, their opposition candidate had won and heard nothing from Milosevic. Milosevic did not leave the capitol.

After a period of time, not long, a few hours and so forth, they began mobilizing and saying, “People need to go to the capitol en masse.” So thousands, tens of thousands from around the country being descending on the capitol in order to peacefully take it back. And what we then saw was a moment in which the police and military, they surrounded the capitol building and were ordered to shoot into the crowd with live bullets. And they didn’t do it. The order never got passed down. And it’s a moment to have in our heads, we don’t know what it’ll look like. It may look very differently, but getting that kind of defection. And at this moment in time, which Trump seems to be able to keep doing anything he wants to do, and that’s one story that people hold, although I don’t think that’s accurate, but it’s one story, it can be hard for us to remember that.

But we really do have to remember the number of people who do not like Trump in his own ranks… Lindsey Graham can’t like him. He sees him as a vehicle for getting some things done. But there are many, many people who would be willing to have knives out inside the Republican Party for Trump if he was perceived as weak. So these things can collapse fairly quickly. And one way we accelerate that is by intentionally and conscientiously thinking of different pillars of support and appealing to them. The primary way of getting defections isn’t protest in the streets. The primary way of getting defections is fraternization, chatting with people and encouraging them to defect. It’s personal relationships. So it’s thinking through who are the people that you know that are in the National Guard, who are the people you know who are in the military, who are people who are in any of these pillars of support?

And I use military as one example, but I shouldn’t lean there because there are many different pillars of support. There are all the contractors who are involved in building these concentration camps, the architects, the builders, carpenters, electricians, all of that. There are all of the people who are implementing his policies at the judicial level, the Supreme Court Justice has been the most dramatic of them, but any of the layers, all the people who are involved in it, there are many forms of noncompliance. What we’re looking for is defections and movement of the population so that we are in collective non-cooperation together. We’re seeing parts of that already, but that’s the architecture of where we’re heading. That’s what it looks like to use a pillar of support to have that moment, that Otpor had. And that was a visceral moment and it’s a clear story, but when they tell that story, it’s a long trajectory. So it’s for us understanding the length of time. There’s many things that we would need to do and we’re doing many of them and there’s more things we can do.

Alex Lovit: If I’m a member of one of these pillars of support, there’s a fairly direct way that I can have an impact. So if I am a National Guard member, I’m a federal judge or something like that, I can withdraw my support from the regime. I might pay a price for that. I might lose my job.

Daniel Hunter: That’s right.

Alex Lovit: But if I’m not a member of the pillar of support, I guess there’s a practical challenge and an emotional challenge. So the practical challenge is figuring out what can I do? What pillar of support could I target? And then the emotional challenge is, you’re talking about people getting beaten up by the police and then telling those police, “You can join us. You’re also a victim.” Can you talk about those two challenges? If I’m trying to think about putting this pillars of support idea into practice, how do I overcome those challenges?

Daniel Hunter: So the first question was about what do you do when you’re analyzing the pillars of support and you’re not seeing yourself in that? You’re seeing yourself outside of it? And it’s important to see yourself in everybody, the entire system is connected to each other. Sure, some pillars are more key than others or whatever, but it’s important that all of us are in some way. So through our consumer behavior, that’s one that we might be able to see the quickest. What are different ways that we are giving money to some of these different capitulating institutions? That’s one of the reasons why economic boycotts have been very important as one of the tactics for large-scale, mass non-cooperation. So we’ve had several examples of that right now. So Avelo is an airline who’s been involved in shuffling people through the deportation process with ICE. And unlike some other airlines who refuse to take part, Avelo continues to support this policy, uphold it. So one way is to put pressure on that company by boycotting it. So people who use Avelo have been saying, “I won’t use Avelo.”

There’s also other companies that we probably have more connections to. Target, for example, has been one of the early capitulators, stripping away its DEI policy, stripping back money that it had promised to the Black community, removing items from the shelves because they might be perceived as pro LGBTQ. And these are policies that were hard won. To get Target even to do this step was a hard won policy, and its capitulation is a signal to everybody else, “It’s okay, we don’t have to, we can step back and pull back from our diversity, so-called values.” So economic boycott is one of the ways in which we are involved. We give our money, I give my money to companies who do some terrible things and are involved in holding up this regime. Stripping ourselves away from that, that’s one way both personally, but also collectively that we’re doing it masse.

So I am trying to honor not just I look at my own personal life and think, “What are these companies? So forth, but I also look for where are there national boycotts that I can join in on so I can add my energy to the collective effort? One person not buying from Amazon isn’t a big thing, but if there’s a national boycott, organized, structured, so we’re looking for a number of different things. There’s also just the element of being part of a citizenry, so keeping the gears going. And so, those of us who might not be in say critical pillars, paying taxes to government, continuing to give credence to the way that we might be celebrating 4th of July, the stories that we are or are not telling, whitewashing of history, all of these are behaviors that we can either comply or not comply with. And the not complying takes some active resistance, takes some choicefulness on our part.

Another element of this, and I’ll just give one more example of the kinds of things that we can be up to, is using our voice to interrupt the silence that’s happening. So when Donald Trump announced that he was doing a takeover of the MPD in Washington, D.C., the police department, when he made that announcement, there’s a group of people in Washington called Free DC, and the day that he made that announcement, they already organized a quick response, getting people to bang pots and pans at 8:00 PM that night. Their urging was, “Silence will be mistaken as acceptance of, as some level of capitulation. Therefore, it’s incumbent on us to raise our voice.” So at the most fundamental level, if we are not in any of the critical pillars as we’re analyzing it, our silence, our not outright in public ways speaking up will be and has been misunderstood.

So we speak up. Right now, Indivisible and the No Kings Coalition has been organizing signs to go up and small businesses around the country to just put up a little poster saying some version of “No ICE. We don’t want you. We love our neighbors,” to assert a public value as part of the contradiction. So that alone will not, of course, stop Donald Trump, but it does give encouragement for other people. People aren’t going to take risks for the most part. People aren’t going to take a lot of risks if they’re not feeling socially backed. They don’t feel like they will be held, respected, seen as courageous acts if their act will just go into history, into obscurity, people are less likely to. People will, and there are some brave people already who’ve been showing some great courage. These are acts of non-cooperation that all of us can take, and they’re very critical. They’re very important because those symbols, again, encourage more defection, encourage more resistance on the whole.

Alex Lovit: And so, what about the emotional challenge of having the strength to say, “You’re welcome to join me even though you beat me up”?

Daniel Hunter: A good political analysis goes a long way. It really does help to analyze, with the pillars of support, “What’s your goal?” We will have to work with the pro-authoritarian portion of this country in the future. They will be in this country. And simply winning, beating them down will not be a successful way to work with our neighbors in the long term. So we need a political vision that is beyond just one side wins and another side loses. It’s one way in which the electoral game has been very unhelpful in this country because it perceives everything as a win-lose scenario, “Our team wins, their team loses.” But the reality of policy, the reality of how we work in the future is, we do have to interact with these folks. That doesn’t mean all of us have to personally interact. So what I say to some of my friends who are fully uninterested, they’re just absolutely not, “I’m not going to work with ICE.” That’s fine. That’s not a role for everybody.

I’m a Quaker and I’ve been telling Quakers, “This is a good role for Quakers.” I want Quakers out there agitating doing what they have a history of doing, which is putting pressure on power holders directly, direct appeal, being on the front lines so that they’re the ones getting beaten up. That’s a historical role that Quakers have been able to play and can play during times like this. So put those people on the front lines so they can be interacting with ICE and saying that kind of thing. For other people, that may be, it doesn’t mean that we all have to be willing to fraternize with… I’m using ICE as an example… It doesn’t mean we have to be willing to fraternize with them, but it may mean that we aren’t making our job, the job of the Quakers, et cetera, harder by simply writing off ICE as horrible human beings who are unredeemable.

Many of the folks, and I’ve had some interactions with folks with ICE, and many of them are extremely conflicted about what they’re being asked to do. There are members and there are stories, for example, of folks who went into ICE because they were trying to stop human trafficking. They’re being pulled off human trafficking cases, human slavery, they’re being pulled off these cases in order to deport members who are embedded in the community, who are well-loved and respected, and they’re watching that happen, and they know it’s wrong. But they don’t necessarily have a pathway. So part of what we have to do is have some offerings for them of what we’re asking them to do. But the political analysis I think is helpful.

But you asked the question, emotionally what do we have to do to get in shape in order to be beaten up and still bounce back? I think some humor helps. It also helps to have some clarity about your goals. I’m saying that in some different ways, but in terms of the emotional stuff, what does it take? What is it that some of the folks do who really face these? I think a lot of us are aware of groups who’ve used faith or religious institutions as a core pillar. So in South Africa, that was a core anchor point, but I’ve been using Otpor as an example, and they did not have a strong religious, that was not one of their core pillars. Instead, for them, it was much more heavy dose of sarcasm. And also having lost and being aware having lost. They did a round where a generation took on Milosevic, tried a much more aggressive, and both, it was a mixture of armed and unarmed struggle, but they took a shot at it and were thoroughly beat down because they weren’t able to move enough people.

The fundamental challenge is to get a lot of the population in motion. So some people, you may have even heard this, it’s sometimes called the 3.5% rule, which I find an unhelpful way to call it. But there’s a body of work where basically they looked at what are the different struggles that were successful in taking out authoritarians. And they found that all of the successful campaigns, whenever they had reached mobilizing 3.5% of the populations at a high moment of one action, one event, one moment in time, whenever they mobilize that amount of the population, the movement was successful. That’s not determinative. I don’t think we need to just think of that as we just need to move that number. But the point here for me is, it’s not that you have to get to 75% of the population in the streets or 50% even, but a significant part of the population being in motion and that resulted in major regime changes.

If we need to get a lot of people, then we need a lot of people. And so our job, wherever we are, is to move people who are not already in motion into action and get them courageous to join protests. Yes, to join acts of non-cooperation, yes, to join public acts and private acts of non-compliance and sabotage. Absolutely. All of that is in the mix in an anti-authoritarian struggle. So the psychology, how do we get there? We get there by keeping our eyes on the prize. Our goal here is not beating Trump. Our goal here is not stopping bad things. Our goal here is bigger than that.

Our goal here is building a society with as many of us as we can, pulling as many people as we can into this new society that has higher values for all people, that respects all people’s rights, bodily autonomy, respects their rights to live in dignity, to have a nation that doesn’t bring in people, economically exploit them. Instead one that has a greater amount of economic quality. These things, these pillars of what we’re going for help anchor us. We want people to come towards that vision. That’s our job.

Alex Lovit: So earlier you said people can play different roles. Not everybody has to do everything. And you also talked about the stakes are high. This is a very important turning point in our history, but yet people have other parts of their lives. So for someone who’s listening to this, who’s thinking, “I want to get involved, I want to do something, but I’ve got someone depending on me, I can’t get arrested. There are limits to what I can do,” what would you say to that person in terms of finding the right task for them, the right level of commitment for them?

Daniel Hunter: So I’d say three things depending on the person. So if you like, a broad analysis. I would say, “Look, it’s helpful just to remind ourselves there are different roles.” So I’ve been writing about four different roles that are commonly seen. So protecting people. Those are folks who are involved in harm reduction, protecting folks who are being targeted personal care. My grandmother, who is Methodist, she was the person who would bake a casserole for everybody. If someone got hurt, no matter whether she liked them or not, she would care for. So protecting people is a very important role. Second was defending civic institutions. So that’s those institutions that are under attack, doing the best to support them, to make sure that they’re being supported and backed, safeguarding the democratic institutions and infrastructure, the elections, EPA, all of those institutions.

The third is disrupting and disobeying. So those, we are the rebels. We get a lot of more attention often for the acts of civil disobedience or dramatized acts of resistance, but that includes any of the public acts of disrupting and disobeying as well as the private acts of protesting policy. And then, the fourth is building alternatives. We need vision of something that’s outside of what we currently have. We need parallel institutions who are ready to take over for some of these institutions that are faltering or failing and are being bled dry right now. We need alternative party platforms and new culture building. And so, all of those are different categories. So protecting people, defending civic institutions, disrupting and disobeying, building alternatives. See yourself in one of those roles. You might be more than one. You might have something that you love. I have my own preferences. I’m not a defending civic institutions person. Just temperamentally, that’s not my way. But also respecting we’re going to need all of these in this moment. So that’s one way to just orient to finding your pathway.

The second thing I would say is there are more and more clear offerings from national organizations for folks who are still looking for how do I find my lane that are steps in. So Free DC I gave as an example, who’s been calling people to support the opposition of the DC takeover. They have been putting out calls and making clear asks of people to share the Free DC sign and participate in the pots and pans at 8:00 PM every night. There’s also other calls like the No Kings Coalition has been a structure who’s been organizing both protests, which people are very welcome to join. I think those are great entry points for people, marches in the streets, get to join with thousands of your friends-to-be in the society we’re heading towards. But also they’ve been inviting people to do… I mentioned some of the activities of putting up signs and posters again through social non-cooperation signaling. Find some of those. They’ve just run a training series, 1 million Rising where they’ve trained hundreds of thousands of people in some of these techniques of non-cooperation. They have videos you can watch. Join with other people.

They’ve been telling people to have house parties as one of their initial acts, to just bring other people to help sort through what is it that we’re hearing about that we’re seeing that we want to do. So have a house party with some of your friends so that you can get in some motion together with some other people. The third thing is, on Choose Democracy’s website, we have a page called What Can I Do? And we’re just trying to help people sort through, scan some different options. So that’s another resource just on Choose Democracy to look at what are some different ways you can plug in. Because there are so many, there’s not one or two activities that are the ones to do. There are many different activities right now, because there are many things being under attack right now, and therefore, there is a range of options. And so, we offer some ways or some specifics that we’ve heard of or seen that are helpful for these times.

Alex Lovit: We’ll put that in the show notes. And one thing I like about that list is that they’re also categorized in easier to do, medium to do and harder to do. So it sort of does give people a sense of, “Okay, if I’m just looking for an entry point, here’s how I can start.”

Daniel Hunter: But do something. If you’re paralyzed… This is what they teach you in the military. They teach you in the military, “If you are frozen, just move.” It’s more important that you’re in motion than it’s the most strategic thing ever. Get in motion, do something. That’s so critical and then find some other people and do some more.

Alex Lovit: You’re drawing from the military there, but I was about to ask you about non-violence, which I know you come from.

Daniel Hunter: I am a non-violence practitioner and many people have learned many things including the military.

Alex Lovit: And when we’re talking about protest or non-compliance, it’s important that those things be non-violent. And I think there’s, of course, a moral argument for that. But what’s the practical argument? Why is it so important to maintain non-violent discipline in order to achieve the results we’re looking for?

Daniel Hunter: So I am entirely a non-violent activist, but let me start by arguing for why acts of violence are meaningful. So I’m going to do the counter argument here just for a second, which is, because many of us saw in L.A. when the National Guard were ordered, they saw violence happening. If you took my kid away from me, all bets are off about how I would act. I’ve done training for years in non-violent resistance, but if I watch you take my kid, I’m not clear how I would react. I just said, “Be in motion,” and Gandhi was a big advocate. He said, “If you don’t know anything else other than violence as a way to stick up for India, do it. Because it is far better to do something than to do nothing.” So I’m taking an unusual position for a non-violent activist to just argue motion is important and we need to understand that.

And that one of the things that non-violent activists have often done is simply told people, “Don’t do that,” and then they look like chiding human beings telling people to not be in motion. That’s not the strategy here. The strategy isn’t restrict until you simply have a small window of things that you’re up to doing. The strategy here, the goal here is to act as much as possible in ways that get and recruit as many people to participate and be involved in. When you look at anti-authoritarian struggles globally, the reason why many of them who pick up armed struggle as a deliberate act, the reason why they struggle to grow is there’s only so many people who are willing to participate in that kind of behavior. Typically is, young men tend to be the people who are most attracted to that, and it very quickly struggles to gain a foothold inside the society.

So our job is to recruit as many people as possible, and therefore, having clear delineations about what we will and will not do, assist people to know, “I’m not going to be involved in an action where we’re throwing rocks at people as part of the thing we’re doing.” And so that’s why non-violent discipline can be so useful. That said, I want us to also be really clear, in these times, about something it’s happening, which is, Trump is using any act as pretense. So the invasion by the military that he ordered into D.C., the takeover of the MPD, the D.C. Police Force, he used a pretense moment where allegedly one of the members of DOGE was involved in a carjacking and he was beaten up. And because of that, Trump is saying D.C. is violent, on and on and on. Trump is going to use pretense and he’s going to attempt to claim any acts on our side are violent. And so, one thing that we need to do is get more sophisticated than simply joining.

And I’m speaking a little bit to some subsect of my non-violent activists who their inclination is to join the decrying acts of violence. But that isn’t how you get discipline. The way we get discipline is getting a clear head on our shoulders about the kinds of behaviors that will be effective and offering people clear vehicles, mass non-cooperation, which is where we need to get to. So we’re in a stages of lots of individual acts and some very meaningful, some very large. No Kings was millions, but we need to get to large-scale, mass non-cooperation. And to do that, we have to offer people actions that are clear. And these are where we talk about general strikes. These are where we talk about large-scale disruption, large-scale tax resistance, large-scale fraternization efforts, these kinds of activities. But the thing I wanted to come back to why non-violence seems to work is because of its ability to recruit more people, a wider base of people, because you have a wider range of tactics that you’re participating in. That said, I do want people in motion. How about that for a take on it?

Alex Lovit: Well, it’s a little surprising.

Daniel Hunter: The fundamental thing for us to do in this moment is to understand there are three steps. Before we get to the third step, which is build the new society we’re looking for, we have to stop the Trump administration, the regime. In order to stop it, you have to slow it down. So this is an awkward phase for us, for people who just want to jump to number three, but we have to slow down. And so, people are getting in the gears, and there is evidence that, in fact, he is slowing down, his ability to… Remember when he was doing executive orders, multiple executive orders every day and it was an onslaught like that.

It still feels like an onslaught, but there are some real indications that we are being successful at slowing down, that there are areas in which we’re able to slow down some of this effort. And so, noticing that doesn’t feel great, but you got to slow it before you stop it, and you got to stop it before you’re able to build the society that you really want. So we’re in that phase right now. I wouldn’t say that we’re doing everything perfect, but I would say that we’re making the progress that we need to make, and I just think we need to keep doing it.

Alex Lovit: Daniel Hunter, thank you for joining me on The Context.

Daniel Hunter: Thank you so much.

Alex Lovit: The Context is a production of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation. Our producers are George Drake Jr. and Emily Vaughn. Melinda Gilmore is our director of communications. The rest of our team includes Jamaal Bell, Tayo Clyburn, Jasmine Olaore, and Darla Minnich. We’ll be back in two weeks with another conversation about democracy. In the meantime, visit our website Kettering.org to learn more about the foundation or to sign up for our newsletter. If you have comments for the show, you can reach us at Thecontext@kettering.org. If you like the show, leave us a rating or a review wherever you get your podcasts, or just tell a friend about us. I’m Alex Lovit. I’m a senior program officer and historian here at Kettering. Thanks for listening.

The views expressed during this program are critical to us having a productive dialogue, but they do not reflect the views or opinions of the Kettering Foundation. The foundation’s broadcast and related promotional activity should not be construed as an endorsement of its content. The foundation hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with this broadcast, which is provided as is and without warranties.

Speaker 3: This podcast is part of the Democracy Group.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a Kettering Foundation contractor and may contain small errors. The authoritative record is the audio recording.

More Episodes

- Published On: July 30, 2024

American democracy relies on nonpartisan civil servants to detect and combat corruption. Alexander Vindman was one such civil servant when he reported...

- Published On: July 16, 2024

The Supreme Court does not belong in the crosshairs of the American political debate. Neal Katyal discusses how the court’s rush to...

- Published On: July 2, 2024

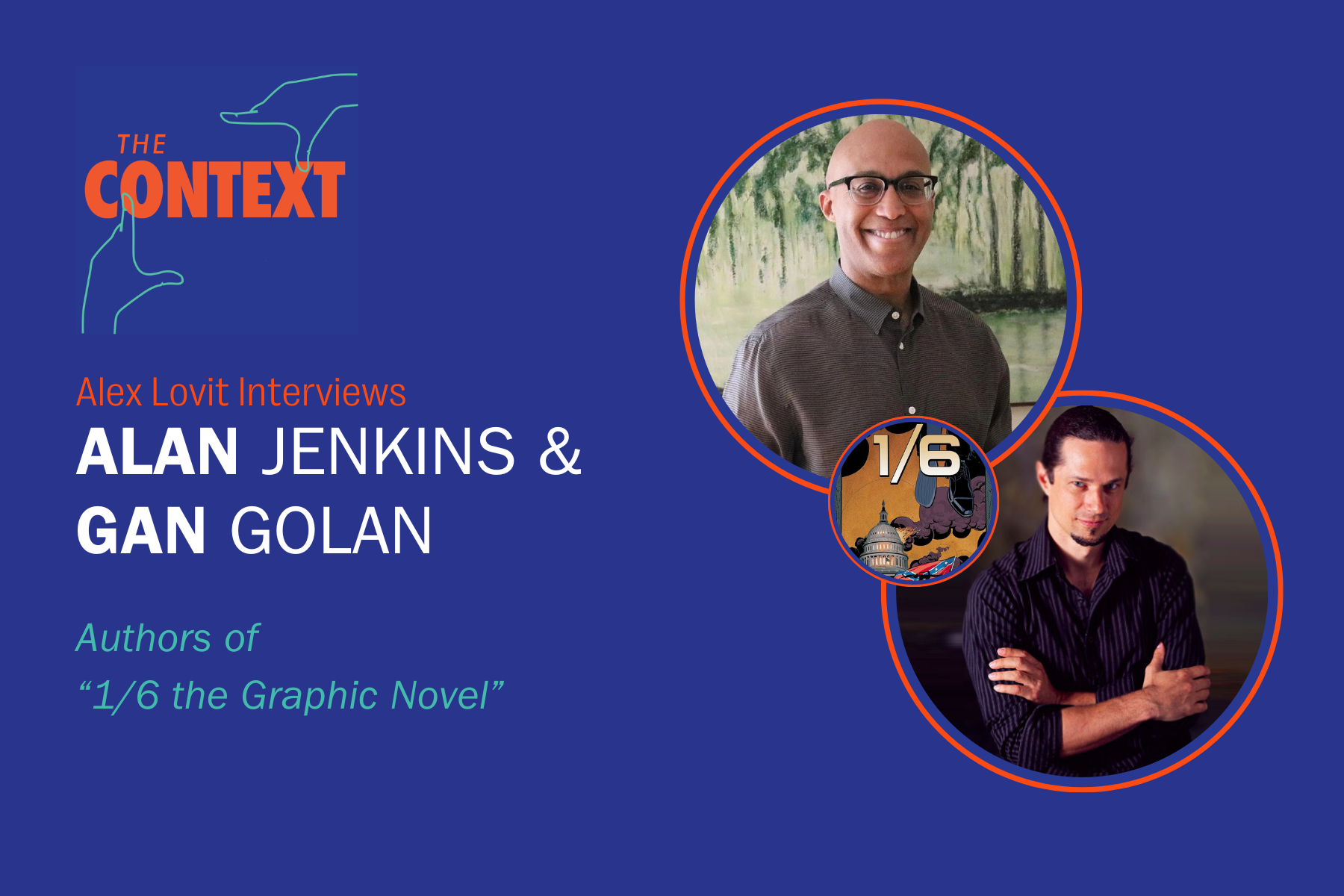

What if the January 6 attack on the US Capitol had been successful? Alan Jenkins and Gan Golan explore just that in...

- Published On: June 18, 2024

The Human Rights Campaign declared a state of emergency for LGBTQ+ Americans for the first time in 2023. In state houses across...

- Published On: June 4, 2024

American voters have never been more dissatisfied. Unlike in business, where more competition promotes accountability and innovation, our political system only allows...

- Published On: May 21, 2024

In commemoration of the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Matthew Delmont discusses the symbolic and practical significance of...