Reconstructing Democracy: Changing Our Minds About Who We Are and What Is Possible

The 2020s have given rise to open racism from right-wing opinion-leaders. Xenophobia has risen across the political spectrum, and Islamophobia and antisemitism have been reinvigorated. The depravities that countless people from many different walks of life spent the first half of the 20th century subduing are all resurgent. Even the most progressive decision-makers have been preoccupied with what K. Sabeel Rahman and Hollie Russon Gillman term “the efficacy and rationality of government action.” Attempts at “good governance” within the civic and institutional context—or even creative and vigorous efforts toward “abundance” policies in housing, environment, and technology—cannot, on their own, stop democratic devolution. To tackle these degenerative problems head-on, we will need to embrace profound changes in the country’s understanding of itself and its ethos. Investment in people, communities, and public goods must become a priority, and our institutions need to be transformed so that they can facilitate and support these efforts. The current moment requires nothing less than a reconstructive politics.

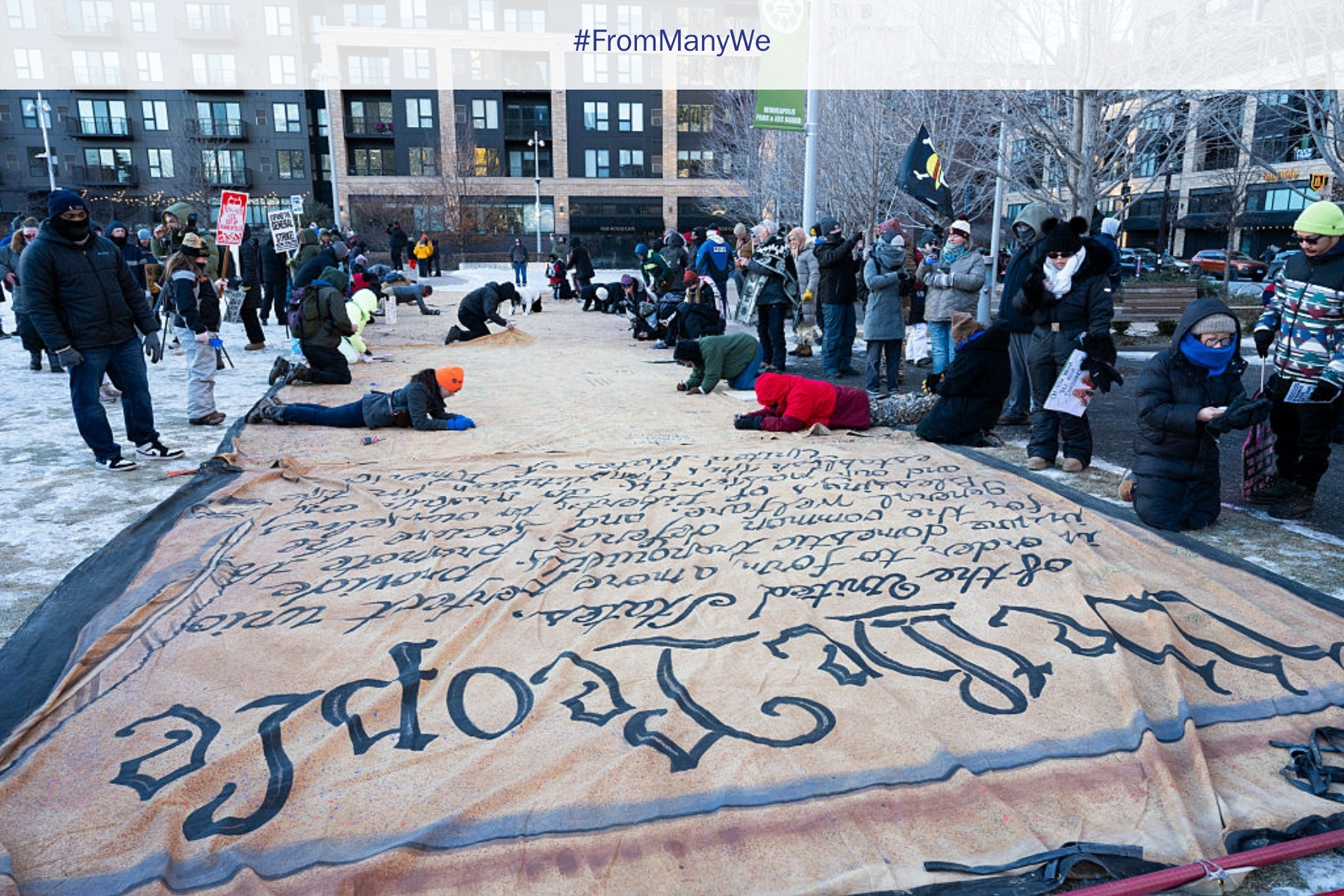

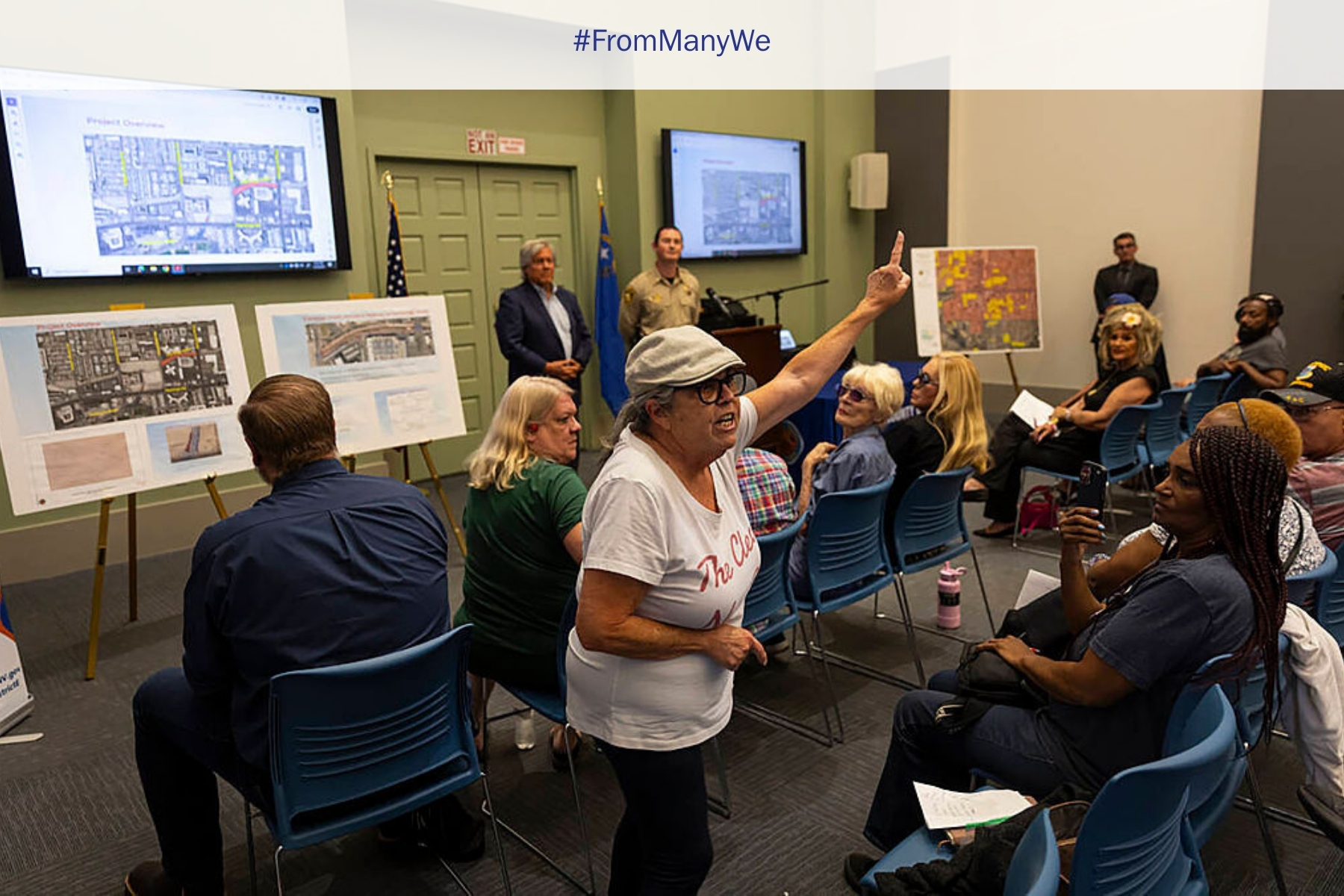

What must we aim to do to nurture more egalitarian democratic relationships and build new parallel institutions in which they can be supported? How are people already taking steps to do so? What will it take to change our minds about who we are as a polity? Reconstructive politics means focusing on the transformations in our institutions and mores that are necessary for us to be able to chart a path toward egalitarian democracy.

America Is Having an Identity Crisis

The US is amid an identity crisis. We are in a moment in which the inclusive democratic narratives of the late 20th century (narratives that were always aspirational and never actual) have lost their status as common sense. The identity of this nation is now being contested, and it is a contest over memory, history, present politics, and possibility. It is the extension of a narrative contest that has been raging since the post–Civil War Reconstruction era. Desmond King and Rogers M. Smith identify this contest as one that pits “racial conservatives [who] swear they will protect traditionalist Americans, especially White Christian men,” against “racial progressives [who] say they will repair the harms experienced by groups damaged by intentional discrimination and institutional racism.” The “protect” versus “repair” paradigms are in a pitched battle, and a politics of reconstruction requires that the contest is settled decisively on the side of democratic repair. A frank and unapologetic commitment to egalitarian democracy is necessary to combat avowed ethnonationalism (the idea that European ethnic heritage and English language use is what makes a person a “real” American). Repairing the harms of structural inequalities of class, race, gender, sexuality (among others), and setting an avowed struggle toward its elimination, must be a priority to accomplish the agenda of reconstructive democracy and to deliver tangible results for the American polity.

An unapologetically pro-egalitarian, pro-democratic politics is not only normatively desirable but also strategically beneficial. There are several empirical reasons to believe unashamedly that pro-democracy politics based on egalitarian values is the best political strategy for aligned politicians and the only way to best anti-democratic opponents.

The Majority of Americans Are Pro-Democracy

Recent findings from the Kettering-Gallup Democracy for All Project poll found large majorities of Americans across parties profess support for basic democratic principles.

- 67% believe that democracy is the best form of government

- 83% reject political violence

- 80% agree that leaders should compromise to get things done

- 84% profess a positive view of American multiculturalism

- 83% support the notion that the wealthy should not be able to have undue influence in government

- 88% believe that the difference between facts and opinions matter

But Many Americans Do Not Trust Key Institutions or Each Other

However, while majorities espouse the above principles, they are also very critical of American institutions and of their representatives and their fellow citizens’ commitment to democracy. Only 37% of Americans report being satisfied with the way democracy is working. According to the Kettering-Gallup poll, majorities do not believe Congress is functioning well, nor do they believe that the criminal justice system is working as it should because people are not treated equally under the law. Additionally, more than 40% of respondents also deem the presidency, the judicial branch, the separation of powers, and the federalist balance of powers between the national government and the states are functioning poorly. Perhaps more surprising, only 49% of Americans believe their fellow citizens are “committed to a strong democracy,” and only 27% believe political leaders are committed to maintaining a strong democracy irrespective of their positions on political issues.

Public Opinion Is Dynamic

Another important lesson for reconstructive politics is that public opinion is dynamic. That is, people change their minds about what issues are important to them, who is to blame for the political problems they are most concerned about, what is to be done, and the scope of desirable possibilities for the future. It is important to remember that public opinion is not inherent, it is shaped by arguments that circulate in the political environment over time. And winning coalitions are built through organizing and by voters who reward representatives that are viewed as authentic and effective, even when they disagree on some policy issues.

But Persuasion Can Take More than an Election Cycle

Public opinion has shifted significantly on immigration. Americans’ desire for deporting immigrants has dropped by nearly half from 55% support in 2024 to 30% support in 2025, and a record 79% of respondents declare that immigration is good for the country. Likewise, we’ve seen shifts in Americans’ ideas about who they trust to handle the economy. An NPR/PBS News/Marist poll taken in late 2025 shows, “now Democrats are slightly more trusted to handle the economy than Republicans—37% to 33%. That’s not a wide margin, but it’s a sharp turnaround from the 16-point advantage Republicans had on the question” as recently as 2022. People have also changed their minds about the seriousness of threats to democracy in just the last year, with concerns about democracy overtaking concerns about the economy. Of course, expanding the timeline of observation, there have been numerous longer term attitude shifts both toward more left-wing and more right-wing positions on gay rights, support for unions, the desirability of government action to provide for basic needs, and more. The important thing to remember is that people’s opinions on political issues and policies are not etched in stone. Politics is a process that is always creating new possibilities for persuasion, and the practice of organizing matters more than it is often credited. People reason about politics by considering their own life experiences, conflicting preferences, and competing values, as well as what they have heard from people they trust and what they believe majorities think, among other considerations. This is why values should anchor political action, even when they lead candidates and advocates to fight for policies that are not (yet) popular. Values are what people should use to develop political strategies that make their favored political positions popular over time. Although this proposition might sound risky, there is extensive evidence that shows that people do change their minds, policy preferences, and political attitudes over time. But that timeline is just longer than a 2- or 4-year election cycle and so is often discounted. However, long-term strategy is crucial for reconstructive politics.

Reconstructive Politics Prioritize Long-Term Vision over Short-Term Gains

While many people may justifiably feel that the current crisis of democracy is too urgent to make any choices that might affect short-term gains, I submit that short-term gains that are not aligned with a long-term vision will not stem the tide of democratic devolution. This is because the problems of inequality that plague American democracy and the endemic resentments that they have produced cannot be solved without changing our minds about what kind of America we are and can become. Egalitarian democracy deserves a full-throated defense. The American people deserve the robust and ambitious agenda toward flourishing that such a defense would make space for in our politics.

Deva Woodly is professor of political science at Brown University and a Charles F. Kettering Foundation research fellow.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.