Reimagine the Future of Democracy: Working to Build an Inclusive Future

At a time when authoritarianism is on the rise and democratic institutions are under strain, the necessity of reimagining and renewing American democracy has never been clearer. To meet this charge, the Kettering Foundation hosted a third-party session during the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Annual Legislative Conference on September 25 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC. The session focused on the transformative power of strategic coalitions, bringing together diverse groups with a shared vision to reimagine and strengthen democracy in the US.

Senior Program Officer for Defending Inclusive Democracy Damien Conners welcomed the standing-room only crowd. He began by describing how we are called not only to defend democracy but also to reimagine it. “To reimagine democracy means refusing to settle for a system that only works for some,” he said. “It means asking boldly and unapologetically, what would democracy look like if it truly included all of us? A democracy that sees, hears, and represents everyone—not just in theory, but in policy, in power, and in practice.”

Conners argued that the work of building an inclusive democracy requires imagination, dreaming, and “leaders who don’t just ask hard questions—they live the answers.” Three such leaders sat on the stage: moderator Joy-Ann Reid, journalist and scholar; and panelists William J. Barber II, Kettering senior fellow, president of Repairers of the Breach, and founding director of the Center of Public Theology and Public Policy at Yale Divinity School; and attorney Maya Wiley, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

To kick off the discussion, Reid asked Wiley, “How far are we down the road to authoritarianism and fascism?”

“I could name all the red lines we’ve already crossed,” said Wiley. She went on to list several: the Supreme Court refusing to be a guardrail; the capitulation of universities, law firms, and large corporations; and the loss of rights that were won in the past.

Building off Wiley’s description of the present, Reid asked Barber to compare today’s environment and work to the time of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Barber drew a connection to Coretta Scott King’s expanded definition of violence: “Violence is denying education. Violence is denying health care. Violence is denying living wages. . . . Even an apathetic attitude that refuses to address these forms of violence is a form of political violence.” He went on to say that violence is perpetrated by politicians who refuse to have real conversations about poverty and low wages, which results in low voter turnout in those communities. And authoritarianism thrives when people “just throw [their] hands up and say nothing.”

Reid agreed, pointing out that in the 1950s and 1960s, “most Black people understood they were in oppression. They knew they were in Jim Crow, and you didn’t have to tell them that. Now what they did about it was a different thing. Not everybody felt they could march . . . but everybody knew what the stakes were.” She described how at the same time, government leaders, such as Democrats in Washington and even a president who may have had racist predilection, all understood the arc of history and that change was needed. Today, institutional safeguards, including the Supreme Court, are gone.

“I think our institutions have been stolen from us,” said Wiley, noting that Black people voted in record numbers in 2008, when Barack Obama won the White House. “There was a specific set of people—who were largely White men—who said, ‘We aren’t going to be a continuing majority of this country.’” She explained that since then, they have been trying to steal Black power by any means necessary, and so they began to build tools like voter ID laws. One example is the Shelby County v. Holder case in 2013, which swept away a key provision from the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Wiley described how it’s not just Blacks who are impacted when institutions are stolen. We’re all affected by the influence of large corporations and policy and tech companies who make money off everyone’s data, she said. With everything that has been stolen, we have an opportunity to rebuild. But instead of rebuilding what was, “it gives us the opportunity to reimagine what should be.”

Reid asked, if institutions have been stolen, how can those who support an inclusive democracy fight the evangelizing of the other side, especially when they receive the backing of billionaires? Barber responded, “I think we have to question whether we give Goliath all the power, or whether we actually believe in the power that we have now. . . . One of the things I’m pushing us to wrestle with is, what are people stealing and what are people giving away?” He reminded the audience that in 1965, “Dr. King said that the greatest fear of a racist oligarchy . . . is for the masses of Negroes and the masses of poor Whites to come together and form a voting block that would fundamentally shift the economic architecture of the country.”

In 2025, poor and low wage people should be motivated to mobilize the vote, Barber argued. He acknowledged that even though they are a large portion of the electorate, this will be difficult because nobody talks to them, they don’t vote, and poverty is not seen as an issue. He challenged the audience to stop acting like they’ve already put forth their best fight, find ways to mobilize all people around issues like health care and a living wage, and show that the same people blocking the Black vote are also attacking the rights of other marginalized groups. “You have to get micro to challenge authoritarianism,” he said. “If you stay macro just on that one leader, you don’t cut the roots off of authoritarianism. You’ve got to get to the roots, and the roots are these senators and others [who pass these bills].”

Part of getting to the micro level is building coalitions. However, “Black folks are feeling very inward turning right now because we [need to] survive this regime first,” said Reid. “Whites are told their interest is in maintaining the power of being White and authority that comes with being White and the opportunity that comes with being White. . . . How do you make the case [for multiracial coalitions] when the other side is pushing so strong, to make White Americans fight for White folks?”

Wiley urged investing, building, and growing power: “I am an angry Black woman, and I don’t care who knows. . . . That means I’m going to care about the Black community . . . [for] what happens to the Black community eventually is coming for everyone. And one salvation is that we recognize building our power can also be done in connection with helping other people see theirs.” She went on to describe building a multiracial coalition that builds up from the Black community.

Barber agreed that focusing on the Black community is important but pointed out that “at some point we are going to have to have a human rights battle,” which requires a new kind of coalition. He referenced his early work in North Carolina, where they had a consistent strategy that was based on an agenda, not a personality, and mobilized in unlikely places. Then, hold politicians accountable—it’s not enough to run against someone, it must be about what you’ll do in the first days in office.

In their closing remarks, both Barber and Wiley focused on the broader picture for democracy. Barber advocated for work at the grassroots level, building coalitions from the bottom up. He said that starts with your area of influence, by fighting within your own organization to do something new. Wiley said that the fight for rights, voice, and citizenship is a fight to solve our problems for everyone. Nothing will change if we can’t have honest conversations about our shared problems and interests, as well as our different problems and interests, and do the hard work.

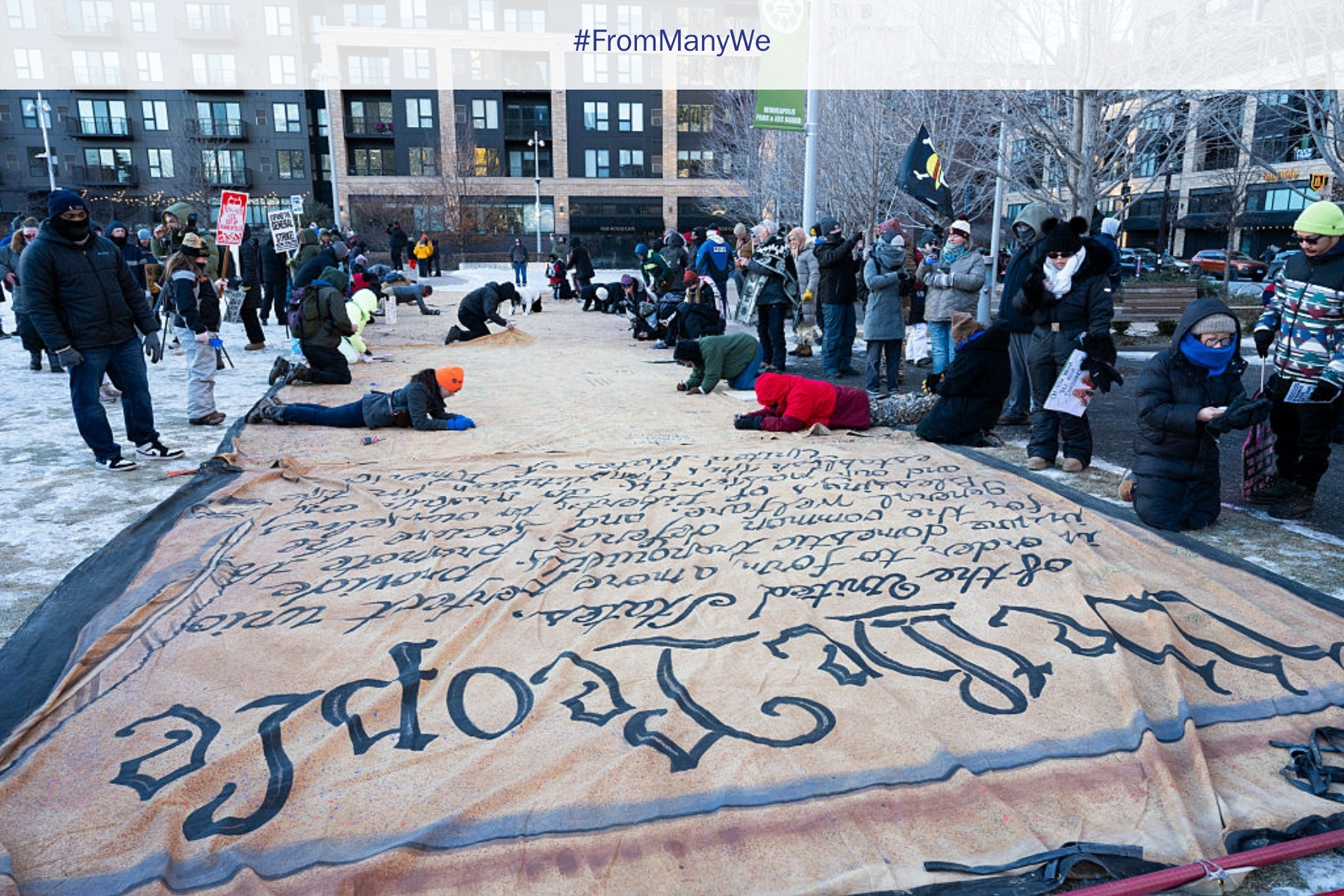

Sharon L. Davies, president and CEO of the Kettering Foundation, ended the session by calling the audience to action. The “worst thing that you could possibly do walking out those doors today would be to walk out of those doors unchanged,” she said. The task now is to work collectively to meet the challenges of the present moment, guided by three commitments: clarity, courage, and coalition. “We must be clear about the gravity of the moment that we are in right now. We must not be deceived about how serious this is and how close we are to losing our democracy,” said Davies. “We must have courage when threats are being carried out and are causing people and institutions to be in fear. . . . Authoritarians know that their greatest foe [is] We the People. Our biggest tool and strength is our numbers.” Democracy needs all of us not just to defend it but also to reimagine it.