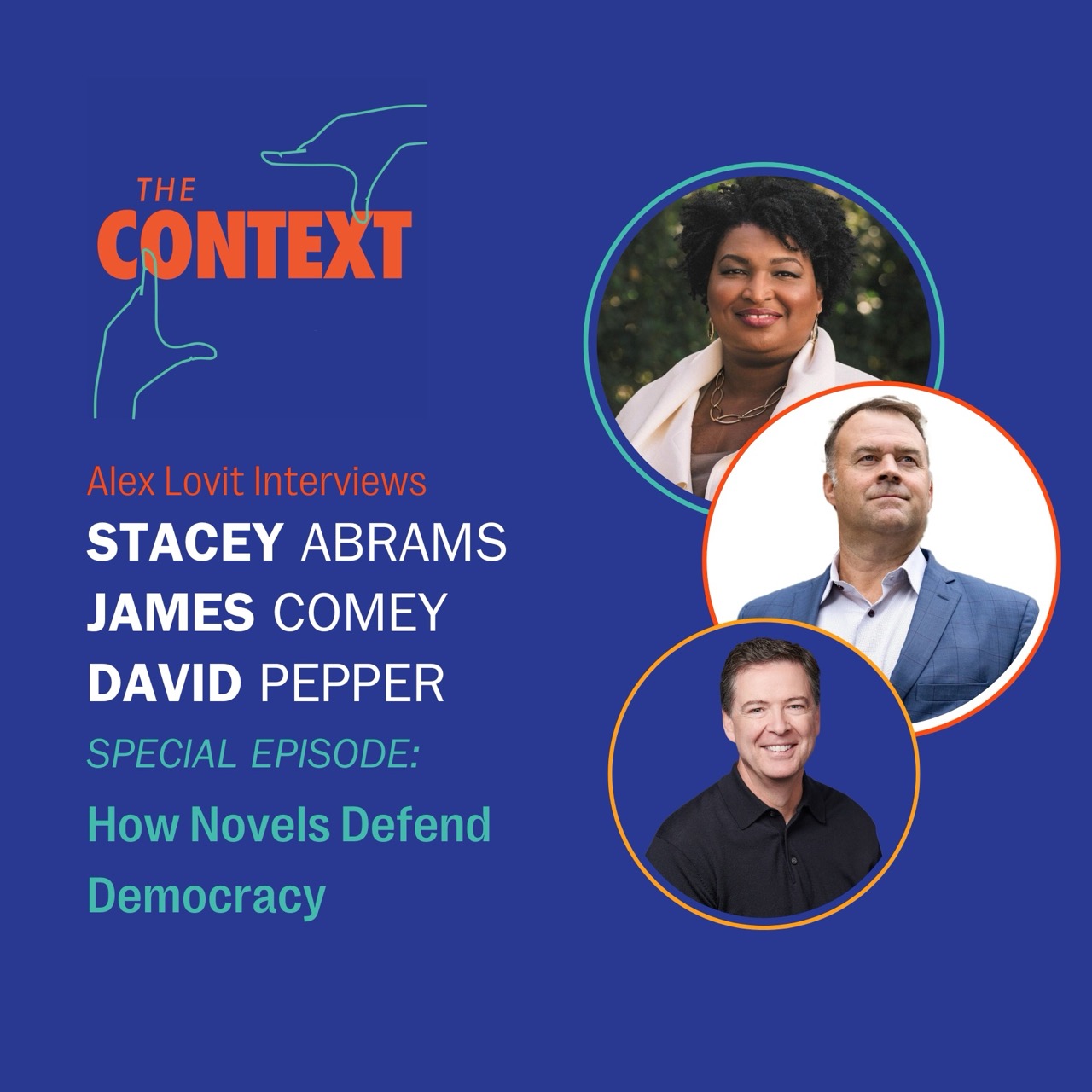

Each of them is best known for their political careers. James Comey served as the director of the FBI; Stacey Abrams served in the Georgia State House of Representatives, including six years as minority leader; and David Pepper served in elected office before becoming chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party. But besides public service, what unites all three of these people is that they all also have had careers as novelists, often drawing from their work in government to depict political and legal issues through fiction.

All three of these people have already been guests on this podcast, but the material you’re about to hear hasn’t previously been shared. I think it’s interesting that all of these very accomplished public figures have made space in their life for creative writing in addition to their public service, and all three of them also see fiction as a way of translating their experience and communicating knowledge and insights about politics and public institutions.

Here at the Kettering Foundation, we believe that artistic expression can help citizens understand and support core democratic values. In fact, one of the five focus areas guiding the Foundation’s work is democracy and the arts. So we agree with Comey, Abrams, and Pepper that fiction can be a way of communicating serious ideas and helping people make meaning of the world they live in.

First up is James Comey talking about his first novel, Central Park West. Since this interview was recorded, Comey has also published his second novel, Westport of communication and openness. You recently wrote a novel, Central Park West, which is informed by your professional experience. You’ve just told me that a sequel is coming out soon. I’m now eagerly anticipating that.

And I don’t want to spoil the book because it’s a fun read, and the twists and the turns in the plot are part of the fun, but to me the book does seem a little cynical. Politicians in it are deceptive. The justice system has limits in determining the truth. But what do you think? Does Central Park West have something to say about the limitations of the justice system, or am I just reading too much into an entertaining crime novel?

James Comey: No, I think you’re reading it right. I wrote it. It reflects my view of the world, which is both optimistic and pessimistic in different measures. And so as I said earlier, what I mean when I talk about the justice system being flawed because it’s run by people is that people often do . . .

And there are no perfectly good people or perfectly bad people. We’re all this mix. People are complicated, and because of that, the system in which they operate is complicated. People lie quite often. Our justice system is designed, consistent with a set of rules—it’s not to find absolute truth but to find truth consistent with a standard of proof: beyond a reasonable doubt.

And one of the things . . . And I, too, will not give stuff away. I hope folks will read it and enjoy it. But one of the lessons of Central Park West is you can know something to be true but not be able to hold someone legally accountable for that because of the burdens that our system of justice—rightly, in my view—impose on prosecutors: to prove something beyond a reasonable doubt.

That can be frustrating for people, but we’ve chosen to strike a balance in this country where we risk letting the guilty go so that we don’t convict the innocent. We still do both of those things—guilty people still get away, and innocent people still get convicted—but the idea behind our justice system is we are best positioned to try and be just if we impose a certain burden on proving something. That’s just the way the world is. And so I’ve tried to communicate in that book both my view of people, that they’re complicated, and my view of the system, that it’s imperfect and strikes balances in a way that often frustrate people.

Alex Lovit: Next is Stacey Abrams talking about her wide-ranging career, including as a prolific author.

You famously developed this spreadsheet back in college that planned out your professional path as an author, as a politician, in business, and you’ve had success in all of those fields. You’ve written—I think 10 novels? I don’t know if I’m up to date.

Stacey Abrams: So actually, I’ve written a total of 18 novels now.

Alex Lovit: Oh, okay. Wow. I’m behind in reading your bibliography. But my question is: Do you see those as sort of separate lines on the spreadsheet—is the fiction an escape from politics—or do you see the fiction as an opportunity to address some of the same public issues that you address in your political career?

Stacey Abrams: So I operate in the public sector, the private sector, the nonprofit sector, and there are tools in all of those sectors to share stories and to create a shared vision of what’s possible. For me, writing began as an outlet, but it quickly became a tool for not only storytelling but for visionmaking. And I see them as interconnected.

I’ve written—at this point, 11 novels have been published. I’ve published three children’s books. I have published four nonfiction works. I’ve got a few more in the offing. In each one of those, my mission is to tell a story about what we can be, and you do so by bringing people in to where we are.

I do the same in my political work. I do the same in my business. My job is to weave together imagination and opportunity and turn it into action. And so I don’t see them as separate. Someone asked me once, “Which lane do you want to eventually be in?” I’m like, “I see my life as a freeway. So I change lanes as necessary, but they’re all heading in the same direction.”

Alex Lovit: Finally, my conversation with David Pepper about the challenges of communicating political messages through fiction.

We’ve primarily been discussing your nonfiction books, Laboratories of Autocracy and Saving Democracy. But you’re a prolific guy. You also write a daily Substack, and you’re a novelist. You’ve written four, I believe, political thrillers now.

And of course, your fiction is informed by your knowledge and experience of politics, including some of the same issues you discuss in your nonfiction. Do you think of those novels as a vehicle to communicate about problems of democracy, or are you just aiming to entertain?

David Pepper: No. Actually, that’s why I wrote the first one. So my first novel . . . So we haven’t covered this. I ran statewide in 2010 for state auditor largely because, if I had won, we could have ended gerrymandering. Then I helped with an initial statewide initiative in 2012 to end gerrymandering, and what I concluded from both my run and that effort was that no one knew anything about gerrymandering.

So my first novel, believe it or not, was an attempt to inform people about gerrymandering through a novel. I called it The People’s House, and it was about how screwed up government is when everything is gerrymandered. Now, the problem is, as a novel sort of marketer, that’s the worst idea for a novel ever. Who wants to read a novel about gerrymandering?

So early on, I thought, “You know what? I’ve got to spice this novel up a little bit.” And again, I had never written a book in my life. I knew nothing about it. I knew nothing of publishing. I added a Russian oligarch because I used to do some work in Russia, and he was the bad guy who took advantage of gerrymandering. He did it in Ohio. And he’s the one looking at gerrymandering as a guy from another country saying, “That’s the most screwed-up system ever, but boy, can I take advantage of it to get what I want.”

And so my first novel was called The People’s House, and—not to tout it too much, but it went viral. Why? Because after the 2016 election, there was a lot of similarity between my Russian bad guy who was rigging American elections and all the talk about what Putin did and others did. The novel really took off , and it was literally . . . It got a lot of coverage as . . . “The novel that predicted the Russia scandal” was how one magazine put it.

But the whole point of that book, from the very beginning, was to use a story and interesting characters to make people see how bad gerrymandering is. And to some degree it worked. My two brothers are very apolitical; but they’re my brothers, so they read my novel. And the novel does . . .

It’s a good story. Most people seem to like it. It got good reviews. It actually got reviewed by the Wall Street Journal, surprisingly[,] in a very positive way. But when my brothers finished that first book, they did say to me, “Boy, that gerrymandering sounds really bad.” And I thought, “Mission accomplished. I got it done.”

And so all of my novels do try to . . . Now, I learned, though, in writing that first book if you try and overpreach in a novel, your novel is bad. A novel has to be about a good story, compelling characters. And there are some lessons that may come out of the story, but if you try and overdo it, you’re writing a bad book.

And so I think I’ve found that balance in my books where it’s always . . . The point is to entertain—good fiction, good stories, good characters—but yeah, part of every novel is also some real-world politics that, I hope, make people see differently the world that they might not have seen before.

I’m a reader of both novels and a lot of nonfiction and a lot of fiction, and I choose whether to do nonfiction or fiction. Sometimes I actually think fiction can be the best way to bring out some aspects of problems more than nonfiction, and my hope is my novels are able to do that sometimes in a way that maybe a nonfiction book would simply be preaching to the choir.

Alex Lovit: So you’re talking there about the challenge of trying to inform readers while also entertain, that it’s challenging to write an entertaining yarn about gerrymandering. In political thrillers as a genre, there tends to be a lot of corruption, dysfunction—and your books don’t lack for that—and it’s harder to tell a story about an honest politician and government agencies working effectively.

David Pepper: Right.

Alex Lovit: Do you worry that fiction about government might contribute to public cynicism and distrust?

David Pepper: Yeah, but—I hate to say it—not as much as the reality of the world right now. I try and capture it . . . My goal has never been to overstate the case. Sure, I have a Russian bad guy figure it out; but what I describe in terms of gerrymandering—or my most recent book, which is called The Fifth Vote, is about corruption—I actually try and capture the reality.

In political thrillers, at least, I never wanted to write a book that a reader would think, “Oh, that’s so unrealistic. That would never happen.” I think I would lose my readers at that point. So I’ll add some thrilling, somewhat—you know, there’s some violence, although not much. I’ll add that to spice up the plot. But the underlying political reality that I try to describe, I would say, is largely how it works—or in some cases, believe it or not . . .

I wrote a book called The Wingman. It’s my second book. It’s a follow up. The first three are sort of a trilogy. It’s all about third parties being used as vehicles—or kind of phony candidates being used as vehicles to undermine the favorite.

Sometimes what I write actually comes true later. We’re seeing that right now. Not everyone is going to agree, but when I see this No Labels and I see Robert Kennedy, it’s literally my plot from a book I wrote seven years ago: Hey, stick another candidate in the middle of an election, and you may pull votes away from the favorite and get your way.

So sometimes if I’ve gotten a little bit into an interesting plot, a couple years later I see it actually playing out. And that’s one reason people have enjoyed my books: A couple years later, they all start writing me saying, “How did you know that was going to happen?”

But I generally try and keep to the world as I see it. If it’s contributing to some cynicism about what’s happening, it may be because I’m describing a reality that some haven’t seen. Again, [interes– ] characters and certain scenes are clearly made up. But the heart of gerrymandering, the heart of corruption in some case as I describe it—I hate to say it—are often based on real-world knowledge or things that I’ve researched.

Alex Lovit: Well, perhaps you should be careful who you inspire if it’s coming true.

David Pepper: Yeah, exactly. [So] I literally had someone on Twitter—I had a few people accuse me of inspiring Putin by describing how you might get involved in an American election and screw up the results, and I would always defend myself . . . Oh, one person actually started following me on Twitter and would always tweet that I was a Russian spy.

And I’d respond, “You . . . “ Well, one, my book didn’t come out early enough that anyone could have modeled their plot off of it. And two, if I really were a spy, would I reveal my plot through a novel before the election took place? But yeah, I’ve had that come up every once in a while: that maybe I should stop because I’m inspiring the wrong people to do the wrong things.

Alex Lovit: Thanks for watching or listening to this special episode of The Context, talking with three people who have combined prominent careers in public service with careers as novelists. If you’re interested in reading any of the books you’ve just heard about, there are links in the show notes. Thanks for watching or listening. Happy New Year, and we’ll be back in a couple of weeks in The Context podcast feed with more conversations about democracy.

The Context is a production of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation. I’m Alex Lovit, a senior program officer and historian with the Foundation. Our director of Communications is Melinda Gilmore. This episode was produced by Jamaal Bell.

The views expressed during this program are critical to us having a productive dialogue, but they do not reflect the views or opinions of the Kettering Foundation. The Foundation’s broadcast and related promotional activities should not be construed as an endorsement of its content. The Foundation hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with this broadcast, which is provided as-is and without warranties.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a Kettering Foundation contractor and may contain small errors. The authoritative record is the audio recording.

More Episodes

- Published On: February 24, 2026

As the United States continues to experience democratic backsliding, people are looking for ways to rise to the moment. But what does...

- Published On: February 10, 2026

Christian nationalists view other religious, cultural, and racial identities as less than fully American. Andrew Whitehead joins host Alex Lovit to discuss...

- Published On: January 27, 2026

Latinos are the largest and fastest growing minority group in the United States, which means they have growing political influence. In recent...

- Published On: January 13, 2026

Free and fair elections are an essential component of democracy. But fair elections face a number of threats in the United States...

- Published On: December 30, 2025

Transparency is essential to hold democratic governments accountable. That requires preserving documents and making them accessible to the public. Colleen Shogan joins...

- Published On: December 16, 2025

We’ve gotten a ton of excellent advice from our guests this year about how everyday people can get involved in fighting authoritarianism...