The Growing Threats of Russian Disinformation on the African Continent

Russian disinformation has been spreading across the African continent. Though the US media has been paying closer attention to the spread of disinformation domestically, disinformation is now a global issue, and solutions to it should also be global in nature. Though the Russian government is not the sole perpetrator, its tactics have proven particularly effective in fostering domestic discord and eroding trust in democratic institutions on the continent. Understanding Russia’s disinformation playbook is critical to disrupting its interference in foreign governments, not only in Africa but also around the world.

Weakening Democracy through Confusion and Uncertainty

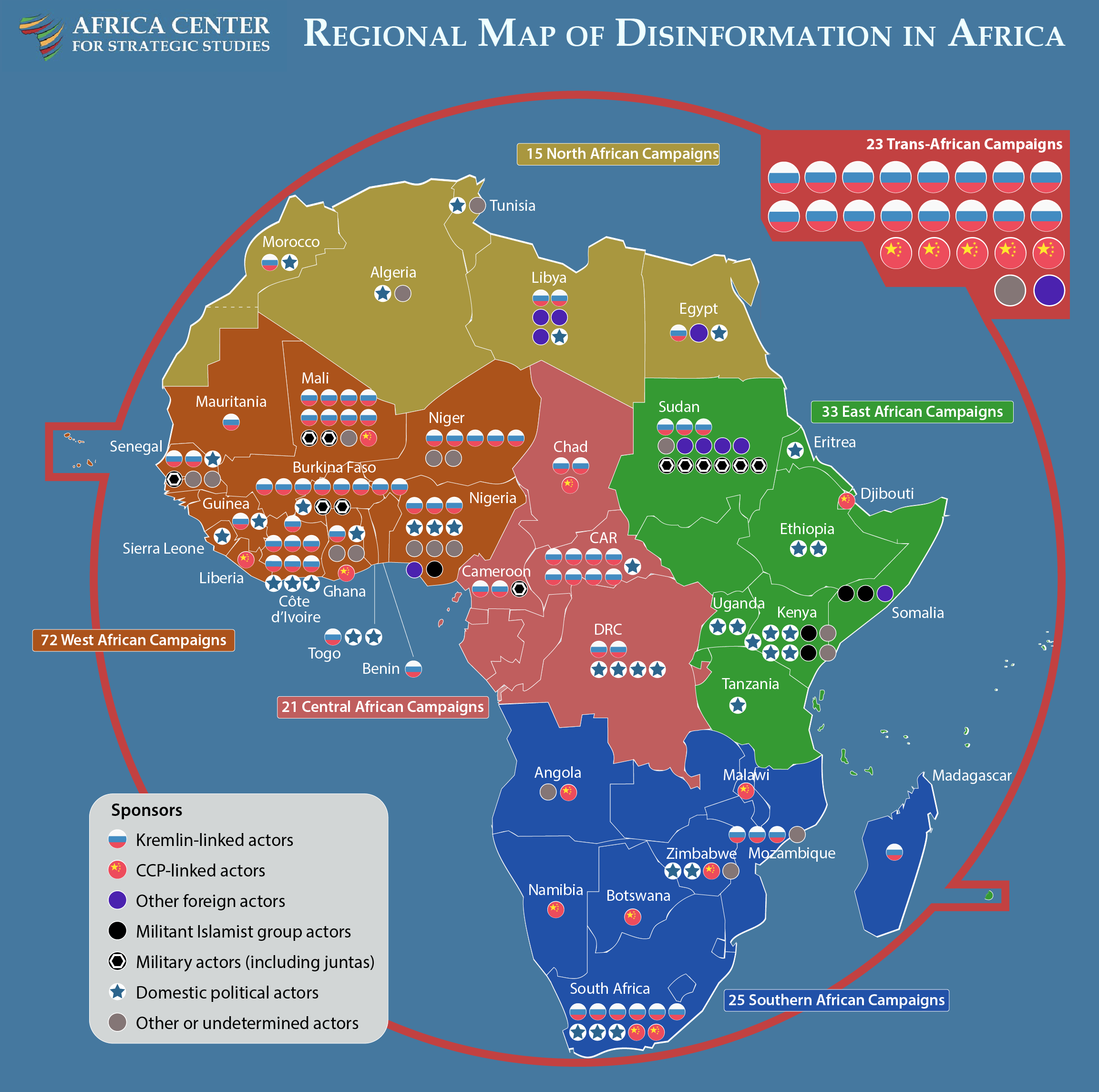

Disinformation campaigns specifically targeting countries of the African continent have nearly quadrupled over the last two years—and at least 40% of these were found to originate from the Russian Federation. Social media use has grown rapidly across the continent, and the ever-evolving sophistication of AI-generated content is fueling the growth of these digital campaigns.

Mapping a Surge of Disinformation in Africa

Disinformation campaigns seeking to manipulate African information systems have surged nearly fourfold since 2022, triggering destabilizing and antidemocratic consequences. (source: Africa Center for Strategic Studies)

Although the content varies, the main strategy of such interference is mostly to create confusion and uncertainty. In 2016, when Russian actors used online disinformation campaigns to interfere in the US presidential elections, the aim was to distract ordinary Americans with unverifiable information leaks and conspiracy theories. These distractions were designed to magnify the existing conflicts that ran along lines of division such as race, party, geography, and culture. The same is true on the African continent today. Journalists have tracked Russia’s traces in disinformation campaigns that, for example, ignited territorial disputes between Madagascar and France and between the Central African Republic and neighboring countries. Sometimes the campaigns are explicitly aimed at keeping a Russia-friendly politician in power or to further a particular economic investment. But in general, the muddier the waters, the better—that is the strategy of Russian interference.

A History of Interference

Russian meddling in African politics has a long history, but the most recent iteration of it can be traced to around 2018. Russian investigative outlet Proekt (founded by Roman Badanin, the coauthor of this essay) published its first story in March 2019 about Russia’s interference in Madagascar. A later article by The New York Times on this topic went on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 2020. Proekt followed with a series of investigations about similar types of interference in Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Guinea, Mali, and more—showing that Russia has meddled in the domestic politics of 20–40 countries on the continent.

At the time, Russia’s motivation was not clear, and many wondered why it was spending its resources in these distant geographic contexts. In some cases, Russia had obvious economic interests, such as obtaining contracts for the extraction of minerals or setting up a military base for its mercenaries, but we still wondered if there was some other motivation for its investment in so much media influence and disinformation. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2024, the answer became clear: Russia was courting the states across the African continent that are all members of the UN and that will play a significant role in any future peace agreement.

The Disinformation and Political Interference Playbook

Across the African continent, we see several common features of Russian interference, both informational and political. It is almost always the case that there is no direct connection between the main channel of influence and the Russian state; instead, disinformation campaigns are carried out with the help of proxies. These proxies used to be predominantly the business structures of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner Group, a private paramilitary group. Even after Prigozhin’s death (most likely at the hands of Vladimir Putin) and the dissolution of Wagner, these business entities and organizations remained in Africa. As recently as September 2024, two former employees of Prigozhin were detained in Chad. They had previously worked under Prigozhin’s orders in Libya, where they had created a pro-Russian TV channel.

Additionally, interference in politics is always accompanied by deliberate attempts to control the information sphere—and, occasionally, to engage in military interference as well. In Libya, for example, the Kremlin simultaneously tried to seize the information field and invest in broadcast media, create a political force loyal to itself, and to wage a war involving both the regular Russian army and its mercenaries. Another example is among the Francophone countries of the continent. There, the Kremlin-linked organization Urpanaf works to achieve political goals. Cameroon-based Afrique Media operates alongside Urpanaf, which is essentially an online publication covering the latter’s political organizing. Afrique’s donors are not disclosed, but it has been clearly linked to the Kremlin’s so-called spin doctors.

Looking Ahead

It would seem that the Kremlin has enough to worry about with the war in Ukraine, and that it should therefore stop its interference in African affairs. Also, the Wagner group has essentially disappeared, and Prigozhin is dead. However, it would be a mistake to think that Russia will no longer engage in disinformation, political influence, and other covert operations in Africa. We have already seen nearly 200 examples of Russia’s continued efforts to sow disinformation and to politically interfere on the continent since the start of the Ukraine invasion. Russia still needs the support of UN-member states across the continent and to continue to reap financial benefits from the political ties it has already established, so these efforts are not likely to abate.

To counter these trends, independent civil society on the continent of Africa continues to need international support. Local independent media, investigative journalists, and organizations that teach media literacy and critical thinking to the next generation are critical for balancing Russia’s outsized investment in the region. We also need to create opportunities for media and narrative change experts from Africa to work in collaboration with their counterparts in other parts of the world. Such partnerships create opportunities to share what they are seeing at a local level with global audiences and would also help to connect the dots on Russia’s disinformation influence in other regions, including in the United States.

Roman Badanin is editor-in-chief of the investigative media outlet Proekt and a JSK Senior International Fellow at Stanford University.

Yelena V. Litvinov is the cofounder of STROIKA Inc., an organization working across thematic and geographic silos to better connect and resource frontline antiauthoritarian activists around the world.

From Many, We is a Charles F. Kettering Foundation blog series that highlights the insights of thought leaders dedicated to the idea of inclusive democracy. Queries may be directed to fmw@kettering.org.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors to our digital communications are made independent of their affiliation with the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and without the foundation’s warranty of accuracy, authenticity, or completeness. Such statements do not reflect the views and opinions of the foundation which hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with statements made by a contributor during their association with the foundation or independently.