The US Doesn’t Have Fair Elections. What Can We Do?

Voting rights are the foundation of democratic governance. But recent changes in elections policies have disenfranchised millions of Americans, and the voting gap between White and minority voters is continuing to expand.

Host Alex Lovit is joined by Sean Morales-Doyle. Morales-Doyle is the director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/ensure-every-american-can-vote

Share Episode

The US Doesn’t Have Fair Elections. What Can We Do?

Voting rights are the foundation of democratic governance. But recent changes in elections policies have disenfranchised millions of Americans, and the voting gap between White and minority voters is continuing to expand.

Host Alex Lovit is joined by Sean Morales-Doyle. Morales-Doyle is the director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/ensure-every-american-can-vote

Share Episode

The US Doesn’t Have Fair Elections. What Can We Do?

Listen & Subscribe

Voting rights are the foundation of democratic governance. But recent changes in elections policies have disenfranchised millions of Americans, and the voting gap between White and minority voters is continuing to expand.

Host Alex Lovit is joined by Sean Morales-Doyle. Morales-Doyle is the director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/ensure-every-american-can-vote

Alex Lovit: Democracies can’t thrive without free and fair elections. All the other rights and freedoms that we associate with democracy, like freedom of speech and equal representation, those depend on everyone having an equal opportunity to make their voices heard at the ballot box.

But that’s not what elections look like in the U.S. today, and some of the biggest steps our country has taken over the past century to make our elections more fair are being erased at an alarming rate. So how do we create the country we want to live in when so many of us are excluded from being able to shape it?

You’re listening to The Context. It’s a show from the Charles F. Kettering Foundation about how to get democracy to work for everyone and why that’s so hard to do. I’m your host, Alex Lovit.

My guest today is Sean Morales-Doyle. He’s the director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. Today we’ll hear from Sean about emerging threats to voting rights, how limitations on ballot access are already influencing our elections, and what we can do to make our elections fair.

Alex Lovit: Sean Morales-Doyle, welcome to The Context.

- Morales-Doyle: Thanks for having me.

Alex Lovit: So one of the biggest developments in voting rights right now is an executive order that President Trump signed back in March. Can you talk about what’s in that executive order? And what is the Brennan Center doing to challenge it?

- Morales-Doyle: The executive order does a number of different things. The president orders this agency called the Election Assistance Commission to start requiring people who register to vote using the federal voter registration form to show a passport or some other document proving their citizenship before they can register.

It also threatens states with certain consequences, like withholding federal funding, if they accept mail ballots that arrive after Election Day but that were mailed on time. And it directs the Department of Justice and DHS and DOGE to, basically, ramp up activities to try to find fraud in our elections.

There have been a number of different lawsuits filed against it, including one that we filed at the Brennan Center with a number of our partners. We got a preliminary injunction from the court against the provision of the executive order requiring people to show a document when they register using the federal form. The president has no constitutional authority to regulate our elections. In federal elections, it’s Congress and the states that run elections.

Alex Lovit: And if that executive order did become policy, how would that affect—you know, how many people would be disenfranchised?

- Morales-Doyle: It could be truly damaging if this executive order were allowed to take effect. The fact is that only about half of American citizens have a passport. And the executive order doesn’t actually make clear what else might count besides a passport; but even assuming that a birth certificate counts, there are 21-plus million American citizens who don’t have a birth certificate, a passport, or a naturalization certificate readily available to them. There are also millions of people who cast ballots by mail that don’t get to the election officials by Election Day.

It’s hard to know exactly what the consequences would be of the provision directing DHS and DOGE to start grabbing voter files and voter rolls from the states and looking through them, but similar efforts in the past to root out nonexistent fraud have resulted in large-scale disenfranchisement of citizens that are knocked off the rolls.

So taken altogether, if this executive order were to actually go into effect, the consequences would be really dramatic and result in millions of people being cut out of our elections.

That’s the practical effect. There’s also this legal effect. The president, again, has no authority to regulate our elections. It’s not the way our Constitution works. There’s a good reason for that: It’s just not a good idea to have one partisan official from one party in the White House having control over our elections.

Alex Lovit: Let’s talk a little bit about recent efforts in Congress. In the last administration, there was the John Lewis Act and the For the People Act. I believe the Brennan Center supported both of those. Can you describe what those would have done?

- Morales-Doyle: Sure. So the Freedom to Vote Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act were two pieces of legislation—are two pieces of legislation. They’ve been reintroduced in this Congress, as well, though they are not likely to go anywhere given the current politics in Congress.

But the Freedom to Vote Act sets a floor for federal elections in the states. It does things like require states to have early voting and to have automatic voter registration, and to have certain rules around mail voting. It essentially makes sure that there’s basic access to our elections available uniformly to voters across the country and puts an end to what’s been happening recently, which is: Your ability to cast a ballot and to go vote increasingly depends on where you live in this country.

The John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would restore the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to its full power. What I mean by that is 12 years ago the United States Supreme Court gutted a critical part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And so the John Lewis Act would restore federal protections against race discrimination in voting and get us back to where we were before those Supreme Court decisions.

And so together these two bills sort of create a set of rules to govern our elections to ensure that there’s access to our elections across the country and then strengthen the protections against someone trying to undermine that system or engage in discrimination in voting.

Alex Lovit: Okay. So as you said, those are proposed bills. They’re still ideas that are out there. We could continue to pass them at any time. Let’s talk about another proposed piece of legislation: the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act, or the SAVE Act, which has passed the House, is currently pending in the Senate. And I think the Brennan Center has opposed that. Can you describe what the SAVE Act is and why it’s a bad idea?

- Morales-Doyle: The SAVE Act is a law that would require anybody registering to vote for federal elections to show a document, like a birth certificate or a passport, every time they register in person to an election official. That would disenfranchise millions of Americans. It would completely undermine some of the more popular forms of registration in this country: registration by mail, online registration.

It would do that because, first of all, 21 million Americans don’t have a birth certificate or a passport handy to show when they register. So that’s 21 million people right there who wouldn’t be able to register if this law were in effect.

Add to that the millions of Americans who have one of those documents but the name on the document doesn’t match their current name—so, for example, someone who changes their name when they get married. Of course, tens of millions of women do that in this country. And so you might have a birth certificate, but the name on the birth certificate doesn’t match your name. So then that’s another level of disenfranchisement that would come from this bill.

But also, again, this requires showing these documents in person every time you register. So if you move and you need to go register to vote again, you’re going to have to go show the document again. You’re going to have to go in person to show that document.

So think about voter-registration drives, where the League of Women Voters sets up a table outside your grocery store and gets you registered to vote. That’s over because you have to show your document in person to an election official to register. Think about registering online, registering by mail. Think about being a military or overseas voter and trying to get registered. This law would completely upset voter registration of many forms, but would also instantly disenfranchise millions of American citizens.

Alex Lovit: So it sounds like the SAVE Act would do a lot of the same negative things that the executive order would do. It did pass the House, so a lot of people voted for it. I think a lot of observers don’t expect it to pass the Senate. Is that your expectation, as well?

- Morales-Doyle: Yes, I do not think the SAVE Act is going to pass out of the Senate. And many, many, many Democratic Senators have made clear that they will not vote for the SAVE Act. And because of the filibuster, there would have to be a number of Democrats who voted in favor of the bill in order for it to pass.

So while the House did pass it, it actually got fewer votes this year than it did last year. Americans across the country have spoken up and gotten pretty upset as they’ve learned more about the SAVE Act. They’ve spoken up, and I think their representatives have heard them.

Alex Lovit: So far in this conversation we haven’t really explicitly addressed partisanship. Voting rights should be a nonpartisan issue. It should just be an issue of democracy that everyone who is eligible to vote should be able to vote.

But of course, when we’re talking about the legislation that would have supported increasing voter access, that was mainly supported by the Democratic Party. When we’re talking about legislation that would decrease voting access, that’s mainly supported by the Republican Party. What’s your understanding of why there’s a partisan divide there? Why does the Republican Party see an interest in limiting voting access?

- Morales-Doyle: That’s a tough one. I can’t speak for the Republican Party. I do want to be clear: that voting rights, as you say, should not be a partisan issue. The Brennan Center is a nonpartisan organization. We’re not advocating for people to be able to vote because of the impact it might have for one party or the other. We’re advocating for voting rights because they’re critically important, fundamental constitutional rights.

Some of it is because, I think, there are politicians who are convinced that making it harder for people to vote will increase their chances of winning. I think that’s shameful. I think that people who want to run for office in this country should win elections by winning over voters, not by trying to keep them from voting.

I also think it’s wrong. I think people who think that suppressing the vote is going to benefit one party or the other are oftentimes wrong. There would be millions of Republicans who would be disenfranchised by the SAVE Act.

But I also think there’s more to it than just that one party has decided that making it harder to vote is good for them politically. This movement to restrict access to voting in the states, and now within our federal government, is driven by a rhetoric about supposed widespread fraud in our elections that has taken on a life of its own.

The 2020 election and President Trump’s attempt to overturn the results took us into a whole new world, where this rhetoric around our elections being rigged is just sort of built into political branding. It’s sort of like a litmus test: whether you agree with the fact that President Biden won the 2020 election, whether you’re willing to stand by the integrity of our elections, or whether you constantly claim falsely that there’s some problem with the integrity of our elections.

And then tacked onto that is anti-immigrant, xenophobic, racist rhetoric. So the most widespread and popular lies around fraud in our elections in the last year or two have been lies about citizenship and voting and the suggestion that there are noncitizens voting in our elections. That’s what’s driving the SAVE Act. That’s what’s being used to justify this executive order by the president. That’s what’s driving lots of activity in state legislatures.

And it is really powerful rhetoric because it combines the “election denier/fraud in our elections” rhetoric with the xenophobic, anti-immigrant rhetoric that is at the core of so much of our politics these days. When you put those two things together, it really animates certain voters. It gets people upset. And now it’s just about buying into this really powerful partisan rhetoric that has become a brand of one of the parties.

Alex Lovit: Why shouldn’t it be hard to vote? Why should we want to make it as easy as possible to vote?

- Morales-Doyle: Well, the basic answer is that the right to vote is a fundamental constitutional right that undergirds all other rights that we have in this country. But also, when we say, “As long as we make it harder for everyone, then everyone’s got to jump through the same hoops,” that’s not the way that it works. When you add extra hoops, when you put obstacles in front of the ballot box, they aren’t felt equally by everybody.

If you limit voting to certain hours on certain days—you know, only in person on Election Day—then someone like me, who’s free to leave my place of work and go cast a ballot during the middle of the work day; people who are privileged to have that freedom; people who are able-bodied and can make it to the polls; people who have the wherewithal to navigate a complicated mail-voting process; people who have the money to go get a new passport that matches the name on their birth certificate—those folks are going to be able to vote.

But there are a lot of people that don’t fall into those categories. There are people who can’t get time away from work or from child care to go cast a ballot. There are people who physically cannot go to the polling place. There are people who aren’t going to be able to spend the money and take the time to go get a passport or a birth certificate.

There are infinite ways in which changing the rules can impact one group more than another group, and we’ve seen how those rules play out for 150 years. So this isn’t a secret or new news. When we had literacy tests, that burden fell differently on different groups of people. When we had poll taxes, it fell differently on different groups of people. When we had grandfather clauses . . .

Those things were intended, obviously, to fall differently on different groups of people, as are some of the rules now. But even when they’re not intended to do that, we have just decades and decades of evidence that when you put obstacles in front of the ballot box for folks, it’s not going to fall equally on everybody.

I think we should all want a democracy that actually reflects the will of the people. And when I say “the people,” I mean all of the people. We should want a democracy where everyone is allowed to participate and, therefore, the outcomes actually reflect what the people want. And if we start locking certain groups of people out of that conversation, we’re causing harm to all of us.

Sometimes when we’re talking about voting rights and democracy, we get caught up in the details about different rules and their effect and that sort of thing, and it’s important we take a step back and ask ourselves, “What are we trying to get out of democracy? What’s the democracy that we want? What’s the democracy that we deserve?”

It’s not just about defending the democracy we have; it’s about having a positive vision for what democracy could look like. It’s about imagining a world in which everybody is participating, everybody’s vote matters, democracy is actually representative and responsive to what people want.

And I think that if you had that democracy . . . We’ve never fully gotten there. I hope we do at some point. But if we did, imagine the impact it would have on people’s real lives. To have government that actually responds to what everybody wants would have a meaningful impact on everybody’s lives, and I think that’s what people really want when they take a step back and think about it.

That’s what people are looking for. They’re looking for a democracy that’s representative, that’s responsive, that’s trustworthy, and that’s inclusive. Once you start from that place—that’s where we’re trying to get—then, I think, it’s just obvious that the answer is we want to make voting as easy as possible for everybody.

Like I said, we want democracy to be trustworthy, too. So of course we want a system that is protected against interference and against fraud and all of those things. That’s an important piece of this. But if you pursue that goal without regard for what it might mean for protecting the fundamental constitutional right to vote for every American citizen, then you’re sacrificing those other core pieces of what democracy is meant to be: representative, responsive, inclusive.

That was maybe a longwinded way to get at it, but it gets back to the initial point, which is: It’s a fundamental constitutional right, and it is a fundamental constitutional right for a reason: because it undergirds all of the other rights that we enjoy as Americans.

Alex Lovit: Yeah. Well, so I, of course, agree with all of that, and I think . . . You were mentioning some of the voting-rights issues of the past, and I think the lesson of that is we can see what happened when those restrictions on the ballot were removed and the way that government really did become more responsive to populations that had previously been excluded.

- Morales-Doyle: That’s right.

Alex Lovit: We’ve been talking about impending threats to voting rights coming from the federal government—so Trump’s executive order, the SAVE Act—but a lot of the action on setting voting regulations is coming from the states. Are there trends that you’re seeing in state governments that you think people should be paying attention to, worried about? Are there any particular examples of states that you think deserve attention right now?

- Morales-Doyle: Really, for a decade-plus now, we’ve seen an unfortunate trend in certain states of attempting to restrict access to voting. Since the Supreme Court’s decision in the Shelby County case that did damage to the Voting Rights Act back in 2013, we’ve seen more than a hundred restrictive voting laws passed by state legislatures.

More recently we’re seeing a lot of activity in state legislatures that mirrors the activity in Congress which is directed towards these conspiracy theories around citizenship and voting. In terms of places where we really need to keep an eye out, Texas has been Ground Zero for attempts to suppress voting for a very long time.

In addition to Texas: Georgia, Florida, Iowa. That may make people think of this as a phenomenon limited to the South. It is not. North Dakota, New Hampshire, Arizona. There are examples, unfortunately, in virtually every region of the country.

For years now, that’s sort of been the main front on which we’re fighting over access to voting, is in the states and in counties within the states, because again, that’s primarily who regulates our elections. The real change in the last few months has been that now there’s a new front on which we’re having this fight, which is a federal administration that is actually trying to actively undermine our democracy in advance of the 2026 elections.

Alex Lovit: Because we’re talking about things happening in the states—so that’s 50 different stories, or even at the county level it’s thousands of stories—it can be a lot to keep track of.

- Morales-Doyle: Mm-hmm.

Alex Lovit: You didn’t mention Ohio, which is where the Kettering Foundation’s office is located. That’s where I live. There’s a bill pending in Ohio that would require proof of citizenship, would require a birth certificate or a passport to vote.

- Morales-Doyle: Yes, and Ohio has also been a focal point for the fight over fair maps in the redistricting process. So Ohio definitely should be on the list.

Alex Lovit: Well, so there’s a lot of states that should be on the list. So it’s a lot for people to keep track of. Do you have any advice for folks that are listening to this and think, “I really don’t know how good the voting rules are in my own state”? How should people find out what’s going on in their own state?

- Morales-Doyle: That’s a good question. It can be a hard thing to keep track of. The Brennan Center does publish a resource a few times a year that we call the Voting Laws Roundup, where, basically, my team every year for more than a decade watches every piece of state legislation concerning voting rights in every state legislature across the country.

At this point, when voting has really become a hot-button partisan topic, that is thousands of pieces of legislation every year. We watch every single one of them. And then on a regular basis we put out an update that we call the Voting Laws Roundup on the trends, what states are considering what, which states have passed laws to restrict access to voting or to expand access to voting or to create the risk of partisan interference in our elections. And so I would recommend that people go check up on the latest Voting Laws Roundup.

I think people should stay in touch with their election officials and their elected officials. Again, most of this activity is happening in state legislatures or in county election boards. So go to your local election board meetings and find out what they’re up to. Talk to your local representative and make sure that they know that you want an inclusive democracy and you want them to be doing things in the state legislature to ensure that happens.

And if people are interested in a[n] even deeper kind of academic research, there are scholars that have created things like the Cost of Voting Index, where they sort of rank states on the level of access that they have. And so those can be more in-depth resources on what the law is in any given state.

Alex Lovit: Yeah, I really like the Cost of Voting Index. And it is complicated poli-sci math that I don’t fully understand, but you can just look at where your state ranks against other states and get a very quick understanding of how much voting access is restricted compared to the rest of the country.

So we’ve been talking about threats that we should be worried about in future from the federal government, state governments. And unfortunately, there’s a lot of threats that we should be worried about in future. I don’t want this conversation to be entirely future tense, though. I think it’s important for people to have a sense of how these issues are already affecting their elections.

- Morales-Doyle: Mm-hmm.

Alex Lovit: Can you just talk about Brennan’s research into gaps in voter turnout among different groups—so different racial groups or other groups? Who tends to turn out to vote at higher rates? Who tends to turn out to vote at lower rates?

- Morales-Doyle: Turnout varies in all kinds of different ways. But unfortunately, in the United States for the last 150 years, race has been a central component of the fight over our democracy and what it’s going to look like. And so one of the things that we pay a lot of attention to at the Brennan Center is the gaps in voting among different racial groups. We call that the “racial turnout gap.”

Historically in the United States, for as long as people who are not white have been allowed to vote, there has almost always been a gap between the turnout of white voters and the turnout of voters of color. White voters tend to turn out at higher rates. Historically a lot of that had to do with active campaigns aimed at stopping people of color from exercising their right to vote.

But it is still the case that there’s a racial turnout gap in most of the country, and that’s between white voters and black voters, between white voters and Latino voters, white voters and Asian voters, white voters and Native voters. The gap varies between those groups. The white/Latino turnout gap, the white/Asian turnout gap, the white/Native turnout gap tend to be bigger than the white/black turnout gap.

But we, a couple years ago, embarked on a pretty intense research project on the racial turnout gap as a way of trying to evaluate where we stand in this country in terms of equal access to voting. We did that for a reason, which is: Back in 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act in the Shelby County decision, they referenced the racial turnout gap as part of the explanation for why they were doing this.

So what I mean by that is the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had this really important piece that was in Section 5 that was called “preclearance.” And what Section 5 did is it required certain jurisdictions in this country, certain states and counties that had a history of race discrimination in voting, to preclear any changes to their voting laws or policies—everything from changing a law down to moving a polling place—by the federal government.

They had to go to the Department of Justice, tell them about the change they were proposing, and demonstrate that it wouldn’t have a racially discriminatory effect before they could put it into effect. That provision, that preclearance practice, was incredibly powerful at stopping race discrimination in this country and completely, dramatically changed the way that democracy functioned in those parts of the country.

And then in 2013, in this Supreme Court case, the Supreme Court basically did away with preclearance. And the reason why was that in their view, Congress hadn’t demonstrated that these were parts of the country that really had a problem with race discrimination in voting anymore.

They said, “Things have changed so much since 1965,” and they specifically said, “Look at the six states that were originally covered by preclearance back in 1965. Back when they were covered, there was dismal turnout. Turnout by black voters was near zero. And now the racial turnout gap has closed, or come close to closing, in those six states.” The Court used that to justify changing this policy.

Justice Ginsburg, in her dissent in that decision, said, “Throwing away preclearance because we’re not seeing the effects of discrimination in these states is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you’re not getting wet.”

We, basically, started looking at the racial turnout gap the last couple years in depth to see whether Justice Ginsburg was right about that, what happened after Shelby County to the racial turnout gap. And what we found was really upsetting because, first of all, what we found is that the racial turnout gap is actually growing across the country. In every part of the country virtually, the racial turnout gap has been growing for the last decade or so.

But what we found relevant to this Shelby County decision is that that growth of the racial turnout gap since the Shelby County decision is twice as fast in the parts of the country that used to have to go through the preclearance process.

So take away preclearance, let these countries and these states start regulating elections without anybody watching, without the prophylactic effect of the preclearance policy, and what you see is the racial turnout gap grows twice as fast in those parts of the country compared to the rest of the country.

Race discrimination in voting is still real. It’s still happening. And while it can be difficult to tease out the impacts on turnout from any one policy, from moving this polling place over here, from changing this voting law in this way—that can take a lot of work by a lot of political scientists with a lot of PhDs—what this research about the racial turnout gap shows is that, on aggregate, when you remove that protection of preclearance, these changes to policy, on aggregate, are having a real damaging impact on the inclusivity of our democracy.

And again, that’s only part of the story because it’s also true that the racial turnout gap is growing nationwide. So it’s not only because of the Shelby County decision, but the Shelby County decision had an impact. There’s a bigger problem that we need to grapple with as a country when we are seeing this gap growing, where people of color are increasingly being left out of the conversation. And I’m talking about millions of votes when I say that.

If that gap closed, if we had equal participation across groups, millions and millions more ballots would be cast in our elections. There are millions of ballots by voters of color that we are losing to this racial turnout gap. There are a lot of reasons for it; but what this study demonstrates is that at least one of the reasons for it, and a really powerful reason for it, are the changes in policies at the county and state level concerning voting.

Alex Lovit: Yeah. So I agree with that, and I think that research is very valuable for exactly that reason: because you could look at turnout gaps for different groups and say, “Well, maybe this group is just more engaged, more interested in voting.” But when policy changes result in differences in the turnout gap, well, it’s pretty obvious that the policies are at least partially to blame there. So you’re saying that we’re losing millions of ballots of people of color that are getting excluded from the system by these policy changes.

- Morales-Doyle: Mm-hmm.

Alex Lovit: Is that a reason to believe that that could have changed elections outcomes? What impact is that having on our elections already?

- Morales-Doyle: Oh, absolutely it could have changed election outcomes. If voters of color were participating at the same level as white voters, the number of ballots that would be injected into our system exceeds the margin of victory for presidential races, for many down-ticket races.

And of course we don’t know which way all those people would vote, so I’m not suggesting that the last election would have gone a different way. We don’t know. But the reality is that the impact on our elections is bigger than the difference between candidates in many, many races along the way. So we could have different outcomes if we had equal participation.

Of course, that’s not the only reason we should care. That’s an important thing, that the elections could actually come out a different way, but it’s not the only thing we should care about. We should care that those voices aren’t being heard. Politicians obviously care about winning or losing; but they also care about who’s voting for them, and they pay attention to who’s voting for them, and they’re more responsive to folks who might not vote for them or might vote for them.

And so dropping huge segments of the population out of that conversation is going to have an impact on election outcomes. It has an impact on policy. It has an impact on public conversations, on narrative, on who government is trying to serve. It should really trouble all of us . . . And that’s just . . .

We’re talking about the racial turnout gap, but it should trouble all of us how low turnout is in this country, period. We do not rank very high in the world when it comes to participation in our elections, and that’s a problem because it means that the people who run our country are not responding to everyone. They’re responding to the people who are participating in our elections, and there should be a lot more people participating in our elections.

Alex Lovit: So all of this is kind of depressing. You might be thinking, “Well, I thought we were a democracy; but now that I’m hearing this, it sounds like it’s easier for some people to vote than others. It’s a pretty skewed democracy.”

- Morales-Doyle: Mm-hmm.

Alex Lovit: How do you think people should respond to that? What’s the appropriate way to think about the ways that our democracy is already damaged?

- Morales-Doyle: Look, we do live in a democracy. It’s flawed. It’s not perfect. It never has been. We’ve repeatedly changed our Constitution in order to allow for more people to participate, but we’ve never gotten there. We’ve never gotten all the way to the democracy that we deserve, and right now we’re in a moment where we are seeing some setbacks.

But I think people should think of this as a story that is, on the whole, a story of progress, and they should think about how we can continue down that road of progress to get to the democracy that we deserve. The reality is that democracy begets democracy. I think that the way to get there is not to throw up our hands and give up on the system that we have, even though it is flawed. It is to actively participate in the system and participate in making it better.

I think the state of Michigan the last few years gives us an example of what I’m talking about here. Prior to 2018, there wasn’t anything getting passed in the Michigan state legislature. Nothing restrictive. Nothing expansive. There was gridlock, and nothing much was happening for their democracy.

But the people of the state of Michigan, clearly, were not happy with the way that their democracy was functioning. They wanted something better. They wanted something different. They went to the ballot box to get it.

They had ballot initiatives on the ballot in 2018 that dramatically changed the way Michigan’s elections would run. They changed the way that maps would be drawn after the 2020 census. They enacted automatic voter registration and same-day registration. They changed the way voting worked in that state.

And so the 2020 census happened. Michigan went and drew a new map with a new independent commission that the voters had voted for that was no longer just a partisan gerrymander by the legislature. They got a map from that independent commission, and then in 2022 they had elections under that map for the first time.

They also, again, put multiple ballot initiatives on the ballot to change their democracy yet again. They protected against attempts to interfere with certification after the 2020 election and Donald Trump trying to interfere with certification there. They further improved their elections in 2022, and then they elected a legislature under this new map and in this new democracy for the first time.

And that new legislature in 2023 passed more expansive voting rights legislation than any other legislature in the country. They went to work immediately and did what the voters had told them to do.

Now you see a legislature that is responsive to voters. They got that by voting. They got that by participating in democracy and sending a message and changing the system through their votes. They got a legislature that actually responded to them and did what they clearly wanted. The voters had made very clear they wanted an expansive democracy, and now that’s what their legislature is doing for them. They’re passing laws to give an expansive democracy.

It’s not always going to go in one direction. We are going to face setbacks. And I understand when Americans are frustrated with the democracy that we have right now. I understand when they see their government doing things they don’t like and they think, “This system doesn’t really work. This system works for the big donors. This system works for who it works for, but not for me.”

But I think the way we get to the democracy we deserve is by participation, is by investment in democracy. The reality is that there are a few checks built into our system against anti-democratic forces, against authoritarianism in the federal government. One of those checks is Congress. Unfortunately, I don’t think Congress is doing what it needs to do to play that role right now.

One of those checks is the courts, and I do think the courts are doing a lot to check authoritarianism right now. But frankly, the federal courts have, for a couple of decades now, retreated from their role of protecting voting rights. So they’re not going to do everything that they need to do, either.

The third check is, really, the people—people going out and making sure that their voices are heard. And that could be through protests. It could be through voting. It could be a lot of different ways. But the only way we’re going to keep this democracy and get to the democracy we all deserve is by people participating and investing in a flawed democracy with the goal of getting to the one that we deserve.

Alex Lovit: Sean Morales-Doyle, thank you for all the work you and the Brennan Center do to protect voting rights around the country, and thank you for joining me on The Context.

- Morales-Doyle: Thanks so much for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Alex Lovit: The Context is a production of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation. Our producers are George Drake, Jr. and Emily Vaughn. Melinda Gilmore is our director of Communications. The rest of our team includes Jamaal Bell, Tayo Clyburn, Jasmine Olaore, and Darla Minnich.

We’ll be back in two weeks with another conversation about democracy. In the meantime, visit our website, kettering.org, to learn more about the Foundation or to sign up for our newsletter. If you have comments for the show, you can reach us at #TheContext at kettering.org. If you like the show, leave us a rating or a review wherever you get your podcasts, or just tell a friend about us. I’m Alex Lovit. I’m a senior program officer and historian here at Kettering. Thanks for listening.

Alex Lovit: The views expressed during this program are critical to us having a productive dialogue, but they do not reflect the views or opinions of the Kettering Foundation. The Foundation’s broadcasts and related promotional activities should not be construed as an endorsement of its content. The Foundation hereby disclaims liability to any party for direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental, or other consequential damages that may arise in connection with this broadcast, which is provided as is and without warranties.

Male Voice: This podcast is part of The Democracy Group.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a Kettering Foundation contractor and may contain small errors. The authoritative record is the audio recording.

More Episodes

- Published On: October 22, 2024

For 49 years, from 1973 until 2022, the Supreme Court declared that the US Constitution protected abortion rights. With this precedent overturned,...

- Published On: October 8, 2024

Latinos are the fastest growing demographic group in the United States and are now the second-largest ethnic group in the country. Growing...

- Published On: September 24, 2024

For democracy to endure, democratic institutions and values must be passed from one generation to the next. And there’s plenty of good...

- Published On: September 10, 2024

In a democracy, we resolve political disagreements through elections rather than through physical force. Political violence is a threat to democratic societies...

- Published On: August 27, 2024

Democracy should work for everyone. Christine Todd Whitman explains how political parties are more concerned with maintaining power than solving problems for...

- Published On: August 13, 2024

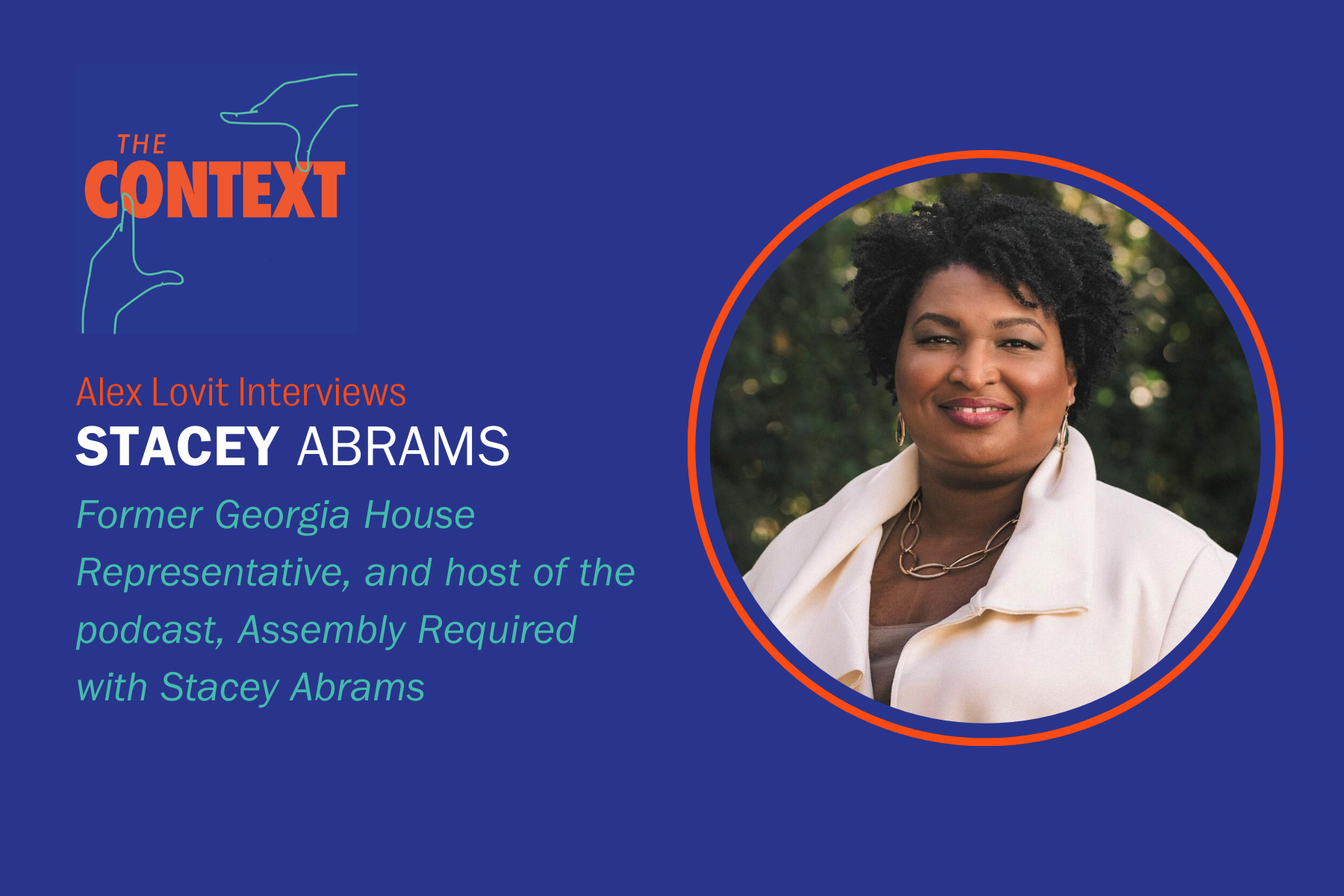

American history is a story about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Stacey Abrams discusses why Americans should embrace and defend DEI as...